3. The Truth about the First Thanksgiving

The Truth about the First Thanksgiving

Considering that virtually none of the standard fare surrounding Thanksgiving contains an ounce of authenticity, historical accuracy, or cross-cultural perception, why is it so apparently ingrained? Is it necessary to the American psyche to perpetually exploit and debase its victims in order to justify its history?

—Michael Dorris

European explorers and invaders discovered an inhabited land. Had it been pristine wilderness then, it would possibly be so still, for neither the technology nor the social organization of Europe in the 16th and 17th centuries had the capacity to maintain, of its own resources, outpost colonies thousands of miles from home.

—Francis Jennings

The Europeans were able to conquer America not because of their military genius, or their religious motivation, or their ambition, or their greed. They conquered it by waging unpremeditated biological warfare.

—Howard Simpson

It is painful to advert to these things. But our forefathers, though wise, pious, and sincere, were nevertheless, in respect to Christian charity, under a cloud; and, in history, truth should be held sacred, at whatever cost... especially against the narrow and futile patriotism, which, instead of pressing forward in pursuit of truth, takes pride in walking backwards to cover the slightest nakedness of our forefathers.

—Col. Thomas Aspinwall

Over the last few years, I have asked hundreds of college students, „When was the country we now know as the United States first settled?“ This is a generous way of phrasing the question; surely „we now know as“ implies that the original settlement antedated the founding of the United States. I initially believed—certainly, I had hoped—that students would suggest 30,000 B.C. or some other pre-Columbian date.

They did not. Their consensus answer was „1620.“

Obviously, my students’ heads have been filled with America’s origin myth, the story of the first Thanksgiving. Textbooks are among the retailers of this primal legend.

Part of the problem is the word settle. „Settlers“ were white, a student once pointed out to me. „Indians“ didn’t settle. Students are not the only people misled by settle. The film that introduces visitors to Plimoth Plantation tells how „they went about the work of civilizing a hostile wilderness.“ One recent Thanksgiving weekend I listened as a guide at the Statue of Liberty talked about European immigrants „populating a wild East Coast.“ As we shall see, however, if Indians hadn’t already settled New England, Europeans would have had a much tougher job of it.

Starting the story of America’s settlement with the Pilgrims leaves out not only the Indians but also the Spanish. The very first non-Native settlers in „the country we now know as the United States“ were African slaves left in South Carolina in 1526 by Spaniards who abandoned a settlement attempt. In 1565 the Spanish massacred the French Protestants who had settled briefly at St. Augustine, Florida, and established their own fort there. Some later Spanish settlers were our first pilgrims, seeking regions new to them to secure religious liberty; these were Spanish Jews, who settled in New Mexico in the late 1500s. Few Americans know that one-third of the United States, from San Francisco to Arkansas to Natchez to Florida, has been Spanish longer than it has been „American,“ and that Hispanic Americans lived here before the first ancestor of the Daughters of the American Revolution ever left England. Moreover, Spanish culture left an indelible mark on the American West. The Spanish introduced horses, cattle, sheep, pigs, and the basic elements of cowboy culture, including its vocabulary: mustang, bronco, rodeo, lariai, and so on. Horses that escaped from the Spanish and propagated triggered the rapid flowering of a new culture among the Plains Indians. „How refreshing it would be,“ wrote James Axtell, „to find a textbook that began on the West Coast before treating the traditional eastern colonies.“

Beginning the story in 1620 also omits the Dutch, who were living in what is now Albany by 1614. Indeed, 1620 is not even the date of the first permanent British settlement, for in 1607, the London Company sent settlers to Jamestown, Virginia.

No matter. The mythic origin of „the country we now know as the United States“ is at Plymouth Rock, and the year is 1620. Here is a representative account from The American Tradition.

After some exploring, the Pilgrims chose the land around Plymouth Harbor for their settlement. Unfortunately, they had arrived in December and were not prepared for the New England winter. How- ever, they were aided by friendly Indians, who gave them food and showed them how to grow corn. When warm weather came, the colonists planted, fished, hunted, and prepared themselves for the next winter. After harvesting their first crop, they and their Indian friends celebrated the first Thanksgiving.

My students also remember that the Pilgrims had been persecuted in England for their religious beliefs, so they had moved to Holland. They sailed on the Mayflower to America and wrote the Mayflower Compact, the forerunner to our Constitution, according to my students. Times were rough until they met Squanto, who taught them how to put a small fish as fertilizer in each little cornhill, ensuring a bountiful harvest. But when I ask my students about the plague, they just stare back at me. „What plague? The Black Plague?“ No, I sigh, that was three centuries earlier.

The Black Plague does provide a useful introduction, however. William Langer has written that the Black (or bubonic) Plague „was undoubtedly the worst disaster that has ever befallen mankind.“ In the years 1348 through 1350, it killed perhaps 30 percent of the population of Europe.

Catastrophic as it was, the disease itself comprised only part of the horror. According to Langer, „Almost everyone, in that medieval time, interpreted the plague as a punishment by God for human sins,“ Thinking the day of judgment was imminent, farmers did not plant crops. Many people gave themselves over to alcohol. Civil and economic disruption may have caused as much death as the disease itself. The entire culture of Europe was affected: fear, death, and guilt became prime artistic motifs. Milder plagues—typhus, syphilis, and influenza, as well as bubonic—continued to ravage Europe until the end of the seventeenth century.

The warmer parts of Europe, Asia, and Africa have historically been the breeding ground for most of humankind’s illnesses. Humans evolved in tropical regions; tropical diseases evolved alongside them. People moved to cooler climates only with the aid of cultural inventions—clothing, shelter, and fire—that helped maintain warm temperatures around their bodies. Microbes that live outside their human hosts during part of their life cycle had trouble coping with northern Europe and Asia. When humans migrated to the Americas across the newly drained Bering Strait, if the archaeological consensus is correct, the changes in climate and physical circumstance threatened even those hardy parasites that had survived the earlier slow migration northward from Africa. These first immigrants entered the Americas through a frigid decontamination chamber. The first settlers in the Western Hemisphere thus probably arrived in a healthier condition than most people on earth have enjoyed before or since. Many of the diseases that had long shadowed them simply could not survive the journey.

Neither did some animals. People in the Western Hemisphere had no cows, pigs, horses, sheep, goats, or chickens before the arrival of Europeans and Africans after 1492. Many diseases—from anthrax to tuberculosis, cholera to streptococcosis, and ringworm to various poxes—are passed back and forth between humans and livestock. Since early inhabitants of the Western Hemisphere had no livestock, they caught no diseases from them.

Europe and Asia were also made unhealthy by a subtler factor: social density. Organisms that cause disease need a constant supply of new hosts for their own survival. This requirement is nowhere clearer than in the case of smallpox, which cannot survive outside a living human body. But in its enthusiasm, the organism often kills its host. Thus the pestilence creates its own predicament: it requires new victims at regular intervals. The various influenza viruses must likewise move on, for if their victims survive, they enjoy a period of immunity lasting at least a few weeks, and sometimes a lifetime. Small-scale societies like the Paiute Indians of Nevada, living in isolated nuclear and extended families, could and did suffer post-Columbian smallpox epidemics, transmitted to them by more urban neighbors, but they could not sustain such an organism over time. Even Indians living in villages did not experience sufficient social density. Villagers might encounter three hundred people each day, but these would usually be the same three hundred people. Coming into repeated contact with the same few others does not have the same consequences as meeting new people, either for human culture or for culturing microbes.

Some areas in the Americas did have high social density. Incan roads connected towns from northern Ecuador to Chile. Fifteen hundred to two thousand years ago, the population of Cahokia, Illinois, numbered about 40,000. Trade linked the Great Lakes to Florida, the Rockies to what is now New England. We are therefore not dealing with isolated bands of „primitive“ peoples. Nonetheless, most of the Western Hemisphere lacked the social density found in much of Europe, Africa, and Asia. And nowhere in the Western Hemisphere were there sinkholes of sickness like London or Cairo, with raw sewage running in the streets.

The scarcity of disease in the Americas was also partly attributable to the basic hygiene practiced by the region’s inhabitants. Residents of northern Europe and England rarely bathed, believing it unhealthy, and rarely removed all of their clothing at one time, believing it immodest. The Pilgrims smelled bad to the Indians. Squanto „tried, without success, to teach them to bathe,“ according to Feenie Ziner, his biographer.

For all these reasons, the inhabitants of North and South America (like Australian aborigines and the peoples of the far-flung Pacific islands) were „a remarkably healthy race“ before Columbus. Ironically, their very health proved their undoing, for they had built up no resistance, genetically or through childhood diseases, to the microbes that Europeans and Africans would bring to them.

In 1617, just before the Pilgrims landed, the process started in southern New England. For decades, British and French fishermen had fished off the Massachusetts coast. After filling their hulls with cod, they would go ashore to lay in firewood and fresh water and perhaps capture a few Indians to sell into slavery in Europe. It is likely that these fishermen transmitted some illness to the people they met. The plague that ensued made the Black Death pale by comparison. Some historians think the disease was the bubonic plague; others suggest that it was viral hepatitis, smallpox, chicken pox, or influenza.

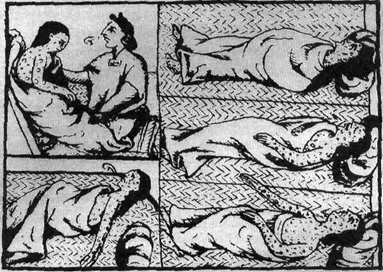

Within three years, the plague wiped out between 90 percent and 96 percent of the inhabitants of coastal New England. The Indian societies lay devastated. Only „the twentieth person is scarce left alive,“ wrote Robert Cushman, a British eyewitness, recording a death rate unknown in all previous human experience. Unable to cope with so many corpses, the survivors abandoned their villages and fled, often to a neighboring tribe. Because they carried the infestation with them, Indians died who had never encountered a white person. Howard Simpson describes what the Pilgrims saw: „Villages lay in ruins because there was no one to tend them. The ground was strewn with the skulls and the bones of thousands of Indians who had died and none was left to bury them.“

During the next fifteen years, additional epidemics, most of which we know to have been smallpox, struck repeatedly. European Americans also contracted smallpox and the other maladies, to be sure, but they usually recovered, including, in a later century, the „heavily pockmarked George Washington.“ Native Americans usually died. The impact of the epidemics on the two cultures was profound. The English Separatists, already seeing their lives as part of a divinely inspired morality play, found it easy to infer that God was on their side. John Winthrop, governor of the Massachusetts Bay Colony, called the plague „miraculous.“ In 1634 he wrote to a friend in England: „But for the natives in these parts, God hath so pursued them, as for 300 miles space the greatest part of them are swept away by the smallpox which still continues among them. So as God hath thereby cleared our title to this place, those who remain in these parts, being in all not 50, have put themselves under our protection..“ God the Original Real Estate Agent!

Many Indians likewise inferred that their god had abandoned them. Robert Cushman reported that „those that are left, have their courage much abated, and their countenance is dejected, and they seem as a people affrighted,“ After a smallpox epidemic the Cherokee „despaired so much that they lost confidence in their gods and the priests destroyed the sacred objects of the tribe.“ After all, neither Indians nor Pilgrims had access to the germ theory of disease. Indian healers could supply no cure; their medicines and herbs offered no relief. Their religion provided no explanation. That of the whites did. Like the Europeans three centuries before them, many Indians surrendered to alcohol, converted to Christianity, or simply killed themselves.

These epidemics probably constituted the most important geopolitical event of the early seventeenth century. Their net result was that the British, for their first fifty years in New England, would face no real Indian challenge. Indeed, the plague helped prompt the legendarily warm reception Plymouth enjoyed from the Wampanoags. Massasoit, the Wampanoag leader, was eager to ally with the Pilgrims because the plague had so weakened his villages that he feared the Narragansetts to the west.“ When a land conflict did develop between new settlers and old at Saugus in 1631, ‘‘God ended the controversy by sending the small pox amongst the Indians,“ in the words of the Puritan minister Increase Mather. „Whole towns of them were swept away, in some of them not so much as one Soul escaping the Destruction,“ By the time the Indian populations of New England had replenished themselves to some degree, it was too late to expel the intruders.

Today, as we compare European technology with that of the „primitive“ Indians, we may conclude that European conquest of America was inevitable, but it did not appear so at the time. The historian Karen Kupperman speculates:

The technology and culture of Indians on America’s east coast were genuine rivals to those of the English, and the eventual outcome of the rivalry was not at first clear..., One can only speculate what the out- come of the rivalry would have been if the impact of European diseases on the American population had not been so devastating. If colonists had not been able to occupy lands already cleared by Indian farmers who had vanished, colonization would have proceeded much more slowly. If Indian culture had not been devastated by the physical and psychological assaults it had suffered, colonization might not have proceeded at all.

After all, Native Americans had driven off Samuel de Champlain when he had tried to settle in Massachusetts in 1606. The following year, Abenakis had helped expel the first Plymouth Company settlement from Maine. Alfred Crosby has speculated that the Norse might have succeeded in colonizing Newfoundland and Labrador if they had not had the bad luck to emigrate from Greenland and Iceland, distant from European disease centers. But this is „what if“ history. The New England plagues were no „if.“ They continued west, racing in advance of the line of culture contact.

Everywhere in America, the first European explorers encountered many more Indians than did their successors. A century and a half after Hernando De Soto traveled the southeastern United States, French explorers there found the population less than a quarter of what it had been when De Soto had passed through, with attendant catastrophic effects on Native culture and social organization. Likewise, on their famous 1806 expedition, Lewis and Clark encountered far more Natives in Oregon than lived there a mere twenty years later.“

Henry Dobyns has put together a heartbreaking list of ninety-three epidemics among Native Americans between 1520 and 1918. He has recorded forty-one eruptions of smallpox, four of bubonic plague, seventeen of measles and ten of influenza (both often deadly among Native Americans), and twenty-five of tuberculosis, diphtheria, typhus, cholera, and other diseases. Many of these outbreaks reached truly pandemic proportions, beginning in Florida or Mexico and stopping only when they reached the Pacific and Arctic oceans. Disease played the same crucial role in Mexico and Peru as it did in Massachusetts, How did the Spanish manage to conquer what is now Mexico City? „When the Christians were exhausted from war, God saw fit to send the Indians smallpox, and there was a great pestilence in the city.“ When the Spanish marched into Tenochtitlan, there were so many bodies that they had to walk on them. Most of the Spaniards were immune to the disease, and that fact itself helped to crush Aztec morale.“

The pestilence continues today. Miners and loggers have recently introduced European diseases to the Yanotnamos of northern Brazil and southern Venezuela, killing a fourth of their total population in 1991. Charles Darwin, writing in 1839, put it almost poetically; „Wherever the European had trod, death seems to pursue the aboriginal.“

Europeans were never able to „settle“ China, India, Indonesia, Japan, or much of Africa, because too many people already lived there. The crucial role played by the plagues in the Americas can be inferred from two simple population estimates: William McNeill reckons the population of the Americas at one hundred million in 1492, while William Langer suggests that Europe had only about seventy million people when Columbus set forth. The Europeans’ advantages in military and social technology might have enabled them to dominate the Americas, as they eventually dominated China, India, Indonesia, and Africa, but not to „settle“ the hemisphere. For that, the plague was required. Thus, apart from the European (and African) invasion itself, the pestilence is surely the most important event in the history of America.

The first epidemics wreaked havoc, not only with Indian societies, but also with estimates of pre-Columbian Native American population. The result has been continuing controversy among historians and anthropologists. In 1840 George Catlin estimated aboriginal numbers in the United States and Canada at the time of white contact to be perhaps fourteen million. He believed only two million still survived. By 1880, owing to warfare and deculturation as well as illness, Native numbers had dropped to 250,000, a decline of 98 percent. In 1921 James Mooney asserted that only one million Native Americans had lived in the Americas in 1492, Mooney’s estimate was accepted until the 1960s and 1970s, even though the arguments supporting it, based largely on inference rather than evidence, were not convincing. Colin McEvedy provided an example of the argument:

The high rollers, of course, claim that native numbers had been reduced to these low levels [between one million and two million] by epidemics of smallpox, measles, and other diseases introduced from Europe—and indeed they could have been. But there is no record of any continental [European] population being cut back by the sort of percentages needed to get from twenty million to two or one million. Even the Black Death reduced the population of Europe by only a third.

Note that McEvedy has ignored both the data and also the reasoning about illness summarized above, relying on what amounts to common sense to disprove both. Indeed, he contended, „No good can come of affronting common sense.“ But pre-Pilgrim American epidemiology is not a field of everyday knowledge in which „common sense“ can be allowed to substitute for years of relevant research. By „common sense“ what McEvedy really meant was tradition.

"The American Republic", the authors of The American Pageant tell us on page one, „was from the outset uniquely favored. It started from scratch on a vast and virgin continent, which was so sparsely peopled by Indians that they were able to be eliminated or shouldered aside.“ Henry Dobyns and Francis Jennings have pointed out that this archetype of the „virgin continent“ and its corollary, the „primitive tribe,“ have subtly influenced estimates of Native population: scholars who viewed Native American cultures as primitive reduced their estimates of precontact populations to match the stereotype. The tiny Mooney estimate thus „made sense“—resonated with the archetype. Never mind that the land was, in reality, not a virgin wilderness but recently widowed.

The very death races that some historians and geographers now find hard to believe, the Pilgrims knew to be true. For example, William Bradford described how the Dutch, rivals of Plymouth, traveled to an Indian village in Connecticut to trade. „But their enterprise failed, for it pleased God to afflict these Indians with such a deadly sickness, that out of 1,000, over 950 of them died, and many of them lay rotting above ground for want of burial…“ This is precisely the 95 percent mortality that McEvedy rejected. On the opposite coast, the Native population of California sank from 300,000 in 1769 (by which time it had already been cut in half by various Spanish-borne diseases) to 30,000 a century later, owing mainly to the gold rush, which brought „disease, starvation, homicide, and a declining birthrate.“

For a century after Catlin, historians and anthropologists „overlooked“ the evidence offered by the Pilgrims and other early chroniclers. Beginning with P. M. Ashburn in 1947, however, research has established more accurate estimates based on careful continent wide compilations of small-scale studies of first contact and on evidence of early plagues. Most current estimates of the precontact population of the United States and Canada range from ten to twenty million.“

How do the twelve textbooks, most of which were published in the 1980s, treat this topic? Their authors might let readers in on the furious debate of the 1960s and early 1970s, telling how and why estimates changed. Instead, the textbooks simply state numbers—very different numbers! „As many as ten million,“ American Adventures proposes. „There were only about 1,000,000 North American Indians,“ opines The American Tradition, „Scattered across the North American continent were about 500 different groups, many of them nomadic.“ Like other Americans who have not studied the literature, the authors of history textbooks are Still under the thrall of the „virgin land“ and „primitive tribe“ archetypes; their most common Indian population estimate is the discredited figure of one million, which five textbooks supply. Only two of the textbooks provide estimates often to twelve million, in the range supported by contemporary scholarship. Two of the textbooks hedge their bets by suggesting one to twelve million, which might reasonably prompt classroom discussion of why estimates are so vague. Three of the textbooks omit the subject altogether.

The problem is not so much the estimates as the attitude. Only one book, The American Adventure, acknowledges that there is a controversy, and this only in a footnote. The other textbooks seem bent on presenting „facts“ for children to „learn.“ Such an approach keeps students ignorant of the reasoning, arguments, and weighing of evidence that go into social science.

About the plagues the textbooks tell even less. Only three of the twelve textbooks even mention Indian disease as a factor at Plymouth or anywhere in New England. Life and Liberty does quite a good job. The American Way is the only book that draws the appropriate geopolitical inference about the Plymouth outbreak, but it doesn’t discuss any of the other plagues that beset Indians throughout the hemisphere. According to Triumph of the American Nation: „If the Pilgrims had arrived at Plymouth a few years earlier, they would have found a busy Indian village surrounded by farmland. As it was, an epidemic had wiped out most of the Indians. Those who survived had abandoned the village,“ „Fortunately for the Pilgrims,“ Triumph goes on, „the cleared fields remained, and a brook of fresh water flowed into the harbor.“ These four sentences exemplify what Michael W. Apple and Linda K. Christian-Smith call dominance through mentioning. The passage can hardly offend Pilgrim descendants, yet it gives the publisher deniability— Triumph cannot be accused of omitting the plague. But the sentences bury the plague within a description of the beautiful harbor at Plymouth. Therefore, even though gory details of disease and death are exactly the kinds of things that high school students remember best, the plague won’t „stick.“ I know, because I never remembered the plague, and my college textbook mentioned it—in a fourteen-word passage nestled within a paragraph about the Pilgrims’ belief in God.

In colonial times, everyone knew about the plague. Even before the Mayflower sailed, King James of England gave thanks to „Almighty God in his great goodness and bounty towards us“ for sending „this wonderful plague among the salvages [j/c].“ Two hundred years later the oldest American history in my collection—]. W. Barber’s Interesting Events in the History of the United States, published in 1829—still recalled the plague.

A few years before the arrival of the Plymouth settlers, a very mortal sickness raged with great violence among the Indians inhabiting the eastern parts of New England. „Whole towns were depopulated. The living were not able to bury the dead; and their bodies were found lying above ground, many years after. The Massachusetts Indians are said to have been reduced from 30,000 to 300 fighting meti. In 1633, the smallpox swept off great numbers.“

Today it is no surprise that not one in a hundred of my college students has ever heard of the plague. Unless they have read Life and Liberty, students could scarcely come away from these books thinking of Indians as people who made an impact on North America, who lived here in considerable numbers, who settled, in short, and were then killed by disease or arms. Textbook authors have retreated from the candor of Barber. Treatments like that in Triumph guarantee our collective amnesia.

Having mistreated the plague, the textbooks proceed to mistreat the Pilgrims. Their arrival in Massachusetts poses another historical controversy that textbook authors take pains to duck. The textbooks say the Pilgrims intended to go to Virginia, where there existed a British settlement already. But „the little party on the Mayflower“ explains American History, „never reached Virginia. On November 9, they sighted land on Cape Cod.“ How did the Pilgrims wind up in Massachusetts when they set out for Virginia? „Violent storms blew their ship off course,“ according to some textbooks; others blame an „error in navigation.“ Both explanations may be wrong. Some historians believe the Dutch bribed the captain of the Mayflower to sail north so the Pilgrims would not settle near New Amsterdam. Others hold that the Pilgrims went to Cape Cod on purpose.

Bear in mind that the Pilgrims numbered only about 35 of the 102 settlers aboard the Mayflower; the rest were ordinary folk seeking their fortunes in the new Virginia colony. George Willison has argued that the Pilgrim leaders, wanting to be far from Anglican control, never planned to settle in Virginia. They had debated the relative merits of Guiana, in South America, versus the Massachusetts coast, and, according to Willison, they intended a hijacking.

Certainly, the Pilgrims already knew quite a bit about what Massachusetts could offer them, from the fine fishing along Cape Cod to that „wonderful plague,“ which offered an unusual opportunity for British settlement. According to some historians, Squanto, an Indian from the village of Patuxet, Massachusetts, had provided Ferdinando Gorges, a leader of the Plymouth Company in England, with a detailed description of the area. Gorges may even have sent Squanto and Capt. Thomas Dermer as advance men to wait for the Pilgrims, although Dermer sailed away when the Pilgrims were delayed in England. In any event, the Pilgrims were familiar with the area’s topography. Recently published maps that Samuel de Champlain had drawn when he had toured the area in 1605 supplemented the information that had been passed on by sixteenth-century explorers, John Smith had studied the region and named it „New England“ in 1614, and he even offered to guide the Pilgrim leaders. They rejected his services as too expensive and carried his guidebook along instead.

These considerations prompt me to believe that the Pilgrim leaders probably ended up in Massachusetts on purpose. But evidence for any conclusion is, soft. Some historians believe Gorges took credit for landing in Massachusetts after the fact. Indeed, the Mayflower may have had no specific destination. Readers might be fascinated if textbook authors presented two or more of the various possibilities, but, as usual, exposing students to historical controversy is I taboo. Each textbook picks just one reason and presents it as fact.

Only one of the twelve textbooks adheres to the hijacking possibility. „The New England landing came as a rude surprise for the bedraggled and tired [non-Pilgrim] majority on board the Mayflower, “ says Land of Promise. „[They] had joined the expedition seeking economic opportunity in the Virginia tobacco plantations.“ Obviously, these passengers were not happy at having been taken elsewhere, especially to a shore with no prior English settlement to join. „Rumors of mutiny spread quickly.“ Promise then ties this unrest to the Mayflower Compact, giving its readers a fresh interpretation of why the colonists adopted the agreement and why it was so democratic: „To avoid rebellion, the Pilgrim leaders made a remarkable concession to the other colonists. They issued a call for every male on board, regardless of religion or economic status, to join in the creation of a „civil body politic.” The compact achieved its purpose: the majority acquiesced.

Actually, the hijacking hypothesis does not show the Pilgrims in such a bad light. The compact provided a graceful solution to an awkward problem. Although hijacking and false representation doubtless were felonies then as now, the colony did survive with a lower death rate than Virginia, so no permanent harm was done. The whole story places the Pilgrims in a somewhat dishonorable light, however, which may explain why only one textbook selects it.

The „navigation error“ story lacks plausibility: the one parameter of ocean travel that sailors could and did measure accurately in that era was latitude—distance north or south from the equator. The „storms“ excuse is perhaps still less plausible, for if a storm blew them off course, when the weather cleared they could have turned southward again, sailing out to sea to bypass any shoals. They had plenty of food and beer, after all. But storms and pilot error leave the Pilgrims pure of heart, which may explain why the other eleven textbooks choose one of the two.

Regardless of motive, the Mayflower Compact provided a democratic basis for the Plymouth colony Since the framers of our Constitution in fact paid the compact little heed, however, it hardly deserves the attention textbook authors lavish on it. But textbook authors clearly want to package the Pilgrims as a pious and moral band who laid the antecedents of our democratic traditions. Nowhere is this motive more embarrassingly obvious than in John Garraty’s American History. „So far as any record shows, this was the first time in human history that a group of people consciously created a government where none had existed before,“ Here Garraty paraphrases a Forefathers’ Day speech, delivered in Plymouth in 1802, in which John Adams celebrated „the only instance in human history of that positive, original social compact.“ George Willison has dryly noted that Adams was „blinking several salient facts—above all, the circumstances that prompted the compact, which was plainly an instrument of minority rule.“ Of course, Garraty’s paraphrase also exposes his ignorance of the Republic of Iceland, the Iroquois Confederacy, and countless other polities antedating 1620. Such an account simply invites students to become ethnocentric.

In their pious treatment of the Pilgrims, history textbooks introduce the archetype of American exceptionalism. According to The American Pageant, „This rare opportunity for a great social and political experiment may never come again.“ The American Way declares, „The American people have created a unique nation.“ How is America exceptional? Surely we’re exceptionally good. As Woodrow Wilson put it, „America is the only idealistic nation in the world.“ And the goodness started at Plymouth Rock, according to our textbooks, which view the Pilgrims as Christian, sober, democratic, generous to the Indians, God-thanking. Such a happy portrait can be painted only by omitting the facts about the plague, the possible hijacking, and the Indian relations.

For that matter, our culture and our textbooks underplay or omit Jamestown and the sixteenth-century Spanish settlements in favor of Plymouth Rock as the archetypal birthplace of the United States. Virginia, according to T. H. Breen, „ill-served later historians in search of the mythic origins of American culture,“ Historians could hardly tout Virginia as moral in intent; in the words of the first history of Virginia written by a Virginian: „The chief Design of all Parties concern’d was to fetch away the Treasure from thence, aiming more at sudden Gain, than to form any regular Colony.“ The Virginians’ relations with the Indians were particularly unsavory: in contrast to Scjuanto, a volunteer, the British in Virginia took Indian prisoners and forced them to teach colonists how to farm.“ In 1623 the British indulged in the first use of chemical warfare in the colonies when negotiating a treaty with tribes near the Potomac River, headed by Chiskiack. The British offered a toast „symbolizing eternal friendship,“ whereupon the chief, his family, advisors, and two hundred followers dropped dead of poison.“ Besides, the early Virginians engaged in bickering, sloth, even cannibalism. They spent their early days digging random holes in the ground, haplessly looking for gold instead of planting crops. Soon they were starving and digging up putrid Indian corpses to eat or renting them- selves out to Indian families as servants—hardly the heroic founders that a great nation requires.

Textbooks indeed cover the Virginia colony, and they at least mention the Spanish settlements, but they devote 50 percent more space to Massachusetts. As a result, and due also to Thanksgiving, of course, students are much more likely to remember the Pilgrims as our founders.59 They are then embarrassed when I remind them of Virginia and the Spanish, for when prompted students do recall having heard of both. But neither our culture nor our textbooks give Virginia the same archetypal status as Massachusetts. That is why almost all my students know the name of the Pilgrims’ ship, while almost no students remember the names of the three ships that brought the British to Jamestown. (For the next time you’re on Jeopardy, they were the Susan Constant, the Discovery, and the Goodspeed.)

Despite having ended up many miles from other European enclaves, the Pilgrims hardly „started from scratch“ in a „wilderness.“ Throughout southern New England, Native Americans had repeatedly burned the underbrush, creating a parklike environment. After landing at Provincetown, the Pilgrims assembled a boat for exploring and began looking around for their new home. They chose Plymouth because of its beautiful cleared fields, recently planted in corn, and its useful harbor and „brook of fresh water.“ It was a lovely site for a town. Indeed, until the plague, it had been a town, for „New Plimoth“ was none other than Squanto’s village of Patuxet! The invaders followed a pattern: throughout the hemisphere Europeans pitched camp right in the middle of Native populations—Cusco, Mexico City, Natchez, Chicago. Throughout New England, colonists appropriated Indian cornfields for their initial settlements, avoiding the backbreaking labor of clearing the land of forest and rock. (This explains why, to this day, the names of so many towns throughout the region— Marshfield, Springfield, Deerfield—end in field) „Errand into the wilderness“ may have made a lively sermon title in 1650, a popular book title in 1950, and an archetypal textbook phrase in 1990, but it was never accurate. The new settlers encountered no wilderness: „in this bay wherein we live,“ one colonist noted in 1622, „in former time hath lived about two thousand Indians.“

Moreover, not all the Native inhabitants had perished, and the survivors now facilitated British settlement. The Pilgrims began receiving Indian assistance on their second full day in Massachusetts. A colonist’s journal tells of sailors discovering two Indian houses:

Having their guns and hearing nobody, they entered the houses and found the people were gone. The sailors took some things but didn’t dare stay… We had meant to have left some beads and other things in the houses as a sign of peace and to show we meant to trade with them. But we didn’t do it because we left in such haste. But as soon as we can meet with the Indians, we will pay them well for what we took.

It wasn’t only houses that the Pilgrims robbed. Our eyewitness resumes his story:

We marched to the place we called Cornhill, where we had found the corn before. At another place we had seen before, we dug and found some more com, two or three baskets full, and a bag of beans In all we had about ten bushels, which will be enough for seed. It was with God’s help that we found this corn, for how else could we have done it, without meeting some Indians who might trouble us.

From the start, the Pilgrims thanked God, not the Indians, for assistance chat the latter had (inadvertently) provided—setting a pattern for later thanksgiving.

Our journalist continues:

The next morning, we found a place like a grave. We decided to dig it up. We found first a mat, and under thai a fine bow,... We also found bowls, trays, dishes, and things like that. We took several of the prettiest things to carry away with us, and covered the body up again.

A place „like a grave“!

Although Karen Kupperman says the Pilgrims continued to rob graves for years, more help came from a live Indian, Squanto. Here my students return to familiar turf, for they have all learned the Squanto legend. Land of Promise provides a typical account:

Squanto had learned their language, he explained, from English fishermen who ventured into the New England waters each summer. Squanto taught the Pilgrims how to plant corn, squash, and pumpkins. Would the small band of settlers have survived without Squanto’s help? We cannot say. But by the fall of 1621, colonists and Indians could sit down to several days of feast and thanksgiving to God (later celebrated as the first Thanksgiving).

What do the books leave out about Squanto? First, how he learned English. According to Ferdinando Gorges, around 1605 a British captain stole Squanto, who was then still a boy, along with four Penobscots, and took them to England. There Squanto spent nine years, three in the employ of Gorges. At length, Gorges helped Squanio arrange passage back to Massachusetts. Some historians doubt that Squanto was among the five Indians stolen in 1605. All sources agree, however, that in 1614 a British slave raider seized Squanto and two dozen fellow Indians and sold them into slavery in Malaga, Spain. What happened next makes Ulysses look like a homebody. Squanto escaped from slavery, escaped from Spain, and made his way back to England. After trying to get home via Newfoundland, in 1619 he talked Thomas Dermer into taking him along on his next trip to Cape Cod.

It happens that Squanto’s fabulous odyssey provides a „hook“ into the plague story, a hook that our textbooks choose not to use. For now Squanto set foot again on Massachusetts soil and walked to his home village of Patuxet, only to make the horrifying discovery that „he was the sole member of his village still alive. All the others had perished in the epidemic two years before,“ No wonder Squanto threw in his lot with the Pilgrims.

Now that is a story worth telling! Compare the pallid account in Land of Promise: „He had learned their language from English fishermen.“

As translator, ambassador, and technical advisor, Squanto was essential to the survival of Plymouth in its first two years. Like other Europeans in America, the Pilgrims had no idea what to eat or how to raise or find it until Indians showed them. William Bradford called Squanto „a special instrument sent of God for their good beyond their expectation. He directed them how to set their corn, where to take fish, and to procure other commodities, and was also their pilot to bring them to unknown places for their profit.“ Squanto was not the Pilgrims’ only aide: in the summer of 1621 Massasoit sent another Indian, Hobomok, to live among the Pilgrims for several years as guide and ambassador.

„Their profit“ was the primary reason most Mayflower colonists made the trip. As Robert Moore has pointed out, „Textbooks neglect to analyze the profit motive underlying much of our history.“ Profit too came from the Indians, by way of the fur trade, without which Plymouth would never have paid for itself. Hobomok helped Plymouth set up fur trading posts at the mouth of the Penob scot and Kennebec rivers in Maine; in Aptucxet, Massachusetts; and in Windso Connecticut. Europeans had neither the skill nor the desire to „go boldly where none dared go before,“ They went to the Indians.

All this brings us to Thanksgiving. Throughout the nation every fall, elementary school children reenact a little morality play, The First Thanksgiving, as our national origin myth, complete with Pilgrim hats made out of construction paper and Indian braves with feathers in their hair. Thanksgiving is the occasion on which we give thanks to God as a nation for the blessings that He [sic] hath bestowed upon us. More than any other celebration, more even than such overtly patriotic holidays as Independence Day and Memorial Day, Thanksgiving celebrates our ethnocentrism. We have seen, for example, how King James and the early Pilgrim leaders gave thanks for the plague, which proved to them that God was on their side. The archetypes associated with Thanksgiving—God on our side, civilization wrested from wilderness, order from disorder, through hard work and good Pilgrim character traits—continue to radiate from our history textbooks. More than sixty years ago, in an analysis of how American history was taught in the 1920s, Bessie Pierce pointed out the political uses to which Thanksgiving is put: „For these unexcelled blessings, the pupil is urged to follow in the footsteps of his forbears, to offer unquestioning obedience to the law of the land, and to carry on the work begun.“

Thanksgiving dinner is a ritual, with all the characteristics that Mircea Eliade assigns to the ritual observances of origin myths:

1. It constitutes the history of the acts of the founders, the Supernatural.

2. It is considered to be true.

3. It tells how an institution came into existence.

4. In performing the ritual associated with the myth, one „experiences knowledge of the origin“ and claims one’s patriarchy.

5. Thus one „lives“ the myth, as a religion.

My Random House dictionary lists as its main heading for the Plymouth colonists not Pilgrims but Pilgrim Fathers. The Library of Congress similarly catalogs its holdings for Plymouth under Pilgrim Fathom, and of course, fathers is capitalized, meaning „fathers of our country,“ not of Pilgrim children. Thanksgiving has thus moved from history into the field of religion, „civil religion,“ as Robert Bellah has called it. To Bellah, civil religions hold society together. Plymouth Rock achieved iconographic status around 1880, when some enterprising residents of the town rejoined its two pieces on the waterfront and built a Greek templet around it. The templet became a shrine, the Mayflower Compact became a sacred text, and our textbooks began to play the same function as the Anglican Book of Common Prayer, teaching us the meaning behind the civil rite of Thanksgiving.

The religious character of Pilgrim history shines forth in an introduction by Valerian Paget to William Bradford’s famous chronicle Of Plimoth Plantation: „The eyes of Europe were upon this little English handful of unconscious heroes and saints, taking courage from them step by step. For their children’s children the same ideals of Freedom burned so clear and strong that... the little episode we have just been contemplating, resulted in the birth of the United States of America, and, above all, of the establishment of the humanitarian ideals it typifies, and for which the Pilgrims offered their sacrifice upon the altar of the Sonship of Man.“ In this invocation, the Pilgrims supply not only the origin of the United States, but also the inspiration for democracy in Europe and perhaps for all goodness in the world today! I suspect that the original colonists, Separatists and Anglicans alike, would have been amused.

The civil ritual we practice marginalizes Indians. Our archetypal image of the first Thanksgiving portrays the groaning boards in the woods, with the Pilgrims in their starched Sunday best next to their almost naked Indian guests. As a holiday greeting card puts it, „I is for the Indians we invited to share our food.“ The silliness of all this reaches its zenith in the handouts that school-children have carried home for decades, complete with captions such as, „They served pumpkins and turkeys and corn and squash. The Indians had never seen such a feast!“ When the Native American novelist Michael Dorris’s son brought home this „information“ from his New Hampshire elementary school, Dorris pointed out that „the Pilgrims had literally never seen ‘such a feast,’ since all foods mentioned are exclusively indigenous to the Americas and had been provided by [or with the aid of] the local tribe.“

This notion that „we“ advanced peoples provided for the Indians, exactly the converse of the truth, is not benign. It reemerges time and again in our his- tory to complicate race relations. For example, we are told that white plantation owners furnished food and medical care for their slaves, yet every shred of food, shelter, and clothing on the plantations was raised, built, woven, or paid for by black labor. Today Americans believe as part of our political understanding of the world that we are the most generous nation on earth in terms of foreign aid, j overlooking the fact that the net dollar flow from almost every Third World nation runs toward the United States.

The true history of Thanksgiving reveals embarrassing facts. The Pilgrims did not introduce the tradition; Eastern Indians had observed autumnal harvest celebrations for centuries. Although George Washington did set aside days for national thanksgiving, our modern celebrations date back only to 1863. During the Civil War, when the Union needed all the patriotism that such an observance might muster, Abraham Lincoln proclaimed Thanksgiving a national holiday. The Pilgrims had nothing to do with it; not until the 1890s did they even get included in the tradition. For that matter, no one used the term Pilgrims until the 1870s.

The ideological meaning American history has ascribed to Thanksgiving compounds the embarrassment. The Thanksgiving legend makes Americans ethnocentric After all, if our culture has God on its side, why should we consider other cultures seriously? This ethnocentrism intensified in the middle of the last century. In Race and Manifest Destiny, Reginald Horsman has shown how the idea of „God on our side“ was used to legitimate the open expression of Anglo-Saxon superiority vis-a-vis Mexicans, Native Americans, peoples of the Pacific, Jews, and even Catholics. Today, when textbooks promote this ethnocentrism with their Pilgrim stories, they leave students less able to learn from and deal with people from other cultures.

On occasion, we pay a more direct cost: censorship. In 1970, for example, the Massachusetts Department of Commerce asked the Wampanoags to select a speaker to mark the 350th anniversary of the Pilgrims’ landing. Frank James „was selected, but first he had to show a copy of his speech to the white people in charge of the ceremony. When they saw what he had written, they would not allow him to read it.“ James had written:

Today is a time of celebrating for you... but it is not a time of celebrating for me. It is with heavy heart that I look back upon what happened to my People... The Pilgrims had hardly explored the shores of Cape Cod four days before they had robbed the graves of my ancestors, and stolen their corn, wheat, and beans... Massasoit, the grear leader of the Wampanoag, knew these facts; yet he and his People welcomed and befriended the settlers… little knowing that... before 50 years were to pass, the Wampanoags... and other Indians living near the settlers would be killed by their guns or dead from diseases that we caught from them Although our way of life is almost gone and our language is almost extinct, we the Wampanoags still walk the lands of Massachusetts. What has happened cannot be changed, but today we work toward a better America, a more Indian America where people and nature once again are important.

What the Massachusetts Department of Commerce censored was not some incendiary falsehood but historical truth. Nothing James would have said, had he been allowed to speak, was false, excepting the word wbeai. Our textbooks also omit the facts about grave robbing, Indian enslavement, the plague, and so on, even though they were common knowledge in colonial New England. For at least a century, Puritan ministers thundered their interpretation of the meaning of the plague from New England pulpits. Thus our popular history of the Pilgrims has not been a process of gaining perspective but of deliberate forgetting. Instead of these important facts, textbooks supply the feel-good minutiae of Squanto’s helpfulness, his name, the fish in the cornhills, sometimes even the menu and the number of Indians who attended the prototypical first Thanksgiving.

I have focused here on untoward detail only because our histories have suppressed everything awkward for so long. The Pilgrims’ courage in setting forth in the late fall to make their way on a continent new to them remains unsurpassed. In their first year, the Pilgrims, like the Indians, suffered from dis eases, including scurvy and pneumonia; half of them died. It was not immoral of the Pilgrims to have taken over Patuxet. They did not cause the plague and were as baffled as to its origin as the stricken Indian villagers. Massasoit was happy that the Pilgrims were using the bay, for the Patuxet, being dead, had no more need for the site. Pilgrim-Indian relations started reasonably positively. Plymouth, unlike many other colonies, usually paid the Indians for the land it took. In some instances Europeans settled in Indian towns because Indians had invited them, as protection against another tribe or a nearby competing European power. In sum, U.S. history is no more violent and oppressive than the history of England, Russia, Indonesia, or Burundi—but neither is it exceptionally less violent.

The antidote to feel-good history is not feel-bad history but honest and inclusive history. If textbook authors feel compelled to give moral instruction, the way origin myths have always done, they could accomplish this aim by’ allowing students to learn both the „good“ and the „bad“ sides of the Pilgrim tale. Conflict would then become part of the story, and students might discover that the knowledge they gain has implications for their lives today. Correct taught, the issues of the era of the first Thanksgiving could help Americans grow more thoughtful and more tolerant, rather than more ethnocentric.

Origin myths do not come cheaply. To glorify the Pilgrims is dangerous. The genial omissions and the invented details with which our textbooks retail the Pilgrim archetype are close cousins of the overt censorship practiced by the Massachusetts Department of Commerce in denying Frank James the right to speak. Surely, in history, „truth should be held sacred, at whatever cost.“

James W. Loewen. Lies My Teacher Told Me: Everything Your American History Textbook Got Wrong. The New Press, 1995.

3. The Truth about the First Thanksgiving, p. 67-90.