11. Progress is Our Most Important Product

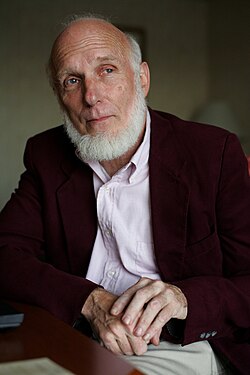

Джеймс У. Лоуен

11.

Progress is Our Most Important Product

James W. Loewen

God has not been preparing the English speaking and Teutonic peoples for a thousand years for nothing...

He has given us the spirit of progress to overwhelm the forces of reaction throughout the earth. He has made us adept in government that we may administer government among savage and senile people... And of all our race He has marked the American people as His chosen nation to finally lead in the redemption of the world.

Senator Albert J. Beveridge, 19001

Americans see history as a straight line and themselves standing at the cutting edge of it as representatives for all mankind.

Frances Fitzgerald2

The study of economic growth is too serious to be left to the economists.

E. J. Mishan3

It is becoming increasingly apparent that we shall not have the benefits of this world for much longer. The imminent and expected destruction of the life cycle of world ecology can only be prevented by a radical shift in outlook from our present naïve conception of this world as a testing ground to a more mature view of the universe as a comprehensive matrix of life forms. Making this shift in viewpoint is essentially religious, not economic or political.

Vine Deloria Jr.4

STEAD FAST READER, we are about to do something no high school American history class has ever accomplished in the annals of American education: reach the end of the textbook. What final words do American history courses impart to their students?

The American Tradition assures students “that the American tradition remains strong—strong enough to meet the many challenges that lie ahead.” “If these values are those on which most Americans can agree,” says The American Adventure, “the American adventure will surely continue.” “Most Americans remained optimistic about the nation’s future. They were convinced that their free institutions, their great natural wealth, and the genius of the American people would enable the U.S. to continue to be—as it always has been—THE LAND OF PROMISE,” Land of Promise concludes.

Even most textbooks that don’t end with their titles close with the same vapid cheer. “The American spirit surged with vitality as the nation headed toward the close of the twentieth century,” the authors of The American Pageant assured us in 1991, ignoring opinion polls that suggest the opposite. Fifteen years later, “The American spirit pulsed with vitality in the early twenty-first century,” they write, but now “grave problems continued to plague the Republic.” Life and Liberty climbs farther out on this hollow limb: “America will have a great role to play in these future events. What this nation does depends on the people in it.” Can’t argue with that! “Problems lie ahead, certainly,” predicts American Adventures. “But so do opportunities.” The American people “need only the will and the commitment to meet the new challenges of the future,” according to Triumph of the American Nation. In short, all we must do to prepare for thе morrow is keep our collective chin up. Or as Holt American Nation put it in 2003, “Americans faced the future with hope and determination.”

Back in 1995, Lies My Teacher Told Me poked fun at textbooks for such endings. Obviously Lies had little influence on textbook publishers.

Well, why not end happily? Might be one response. We don’t want to depress high school students. After all, it’s not really history anyway—we cannot know for sure what’s going to come next. So let’s end on an upbeat.

Indeed, just as we don’t know with precision what went on thousands of years ago, we cannot know with precision what will happen next. Precisely for this reason, the endings of these books provide another site where authors might appropriately provoke intellectual curiosity. Can students apply ideas they have learned from these huge American history textbooks? After all, as Shakespeare said, “the past is prologue.” If we understand what has caused what in the past, we may be able to predict what will happen next and even adopt national policies informed by our knowledge. Surely helping students learn to do so is the key reason for teaching history in the first place. If history textbooks supplied tools for projection or examples of causation in the past that might (or might not) continue into the future, they would encourage students to think about what they have just spent a year learning. What a thrilling way to end a history textbook!

According to American History, Westward the Course of Empire Takes Its Way has been reproduced in more American histories than any other picture by Currier and Ives. Stereotypically contrasting “primitive” Native hunters and fishers with bustling white settlers, the picture suggests that progress doomed the Indian, so we need not look closely today at the process of dispossession.

But no, the lack of intellectual excitement in these books is most pronounced at their ends. All is well, the authors soothe us. Just keep on keepin’ on. No need to ponder whether the nation or all humankind is on the right path. No need to think at all. Not only is this boring pedagogy, it’s bad history. Nevertheless, endings like these are customary.

As usual, such content-free unanimity signals that a social archetype lurks nearby. This one, the archetype of progress, bursts forth in full flower on the textbooks’ last pages but has been germinating from their opening chapters.

For centuries, Americans viewed their own history as a demonstration of the idea of progress. As Thomas Jefferson put it:

Let the philosophical observer commence a journey from the savages of the Rocky Mountains eastwards towards our seacoast. These he would observe in the earliest stage of association, living under no law but that of nature He would next find those on our frontiers in the pastoral state, raising domestic animals to supply the defects of hunting,... and so in his progress he would meet the gradual shades of improving man until he would reach his, as yet, most improved state in our seaport towns. This, in fact, is equivalent to a survey, in time, of the progress of man from the infancy of creation to the present day. And where this progress will stop no one can say.5

The idea of progress dominated American culture in the nineteenth century and was still being celebrated in Chicago at the Century of Progress Exposition in 1933. As recently as the 1950s, more was still assumed to be better. Every Midwestern town displayed civic pride in signs marking the city limits: WELCOME TO DECATUR, ILLINOIS, POP. 65,000 AND GROWING.

Growth meant progress, and progress provided meaning, in some basic but unthinking way. In Washington the secretary of commerce routinely celebrated when our nation hit each new milestone—170,000,000, 185,000,000, etc.—on his “population clock.”6 We boasted that America’s marvelous economic system had given the United States “72 percent of the world’s automobiles, 61 percent of the world’s telephones, and 92 percent of the world’s bathtubs,” and all this with only 6 percent of the world’s population.7 The future looked brighter yet: most Americans believed their children would inherit a better planet and enjoy fuller lives.

This is the America in which most textbook authors grew up and the America they still try to sell to students today. Perhaps textbooks do not question the notion that bigger is better because the idea of progress conforms with the way Americans like to think about education: ameliorative, leading step by step to opportunity for individuals and progress for the whole society. The ideology of progress also provides hope for the future. Certainly most Americans want to believe that their society has been, on balance, a boon and not a curse to mankind and to the planet.8 History textbooks go even further to imply that simply by participating in society, Americans contribute to a nation that is constantly progressing and remains the hope of the world. As Boorstin and Kelley put it, near the end of A History of the United States, “Americans— makers of something out of nothing—have delivered a new way of life to far corners of the world.” Thus, the idea of American exceptionalism—the United States as the best country in the world—which starts in our textbooks with the Pilgrims, gets projected into the future.

In the 1950s a graphics firm redesigned the symbol for Explorer Scouting to be more “up to date.” The new symbol’s onward and upward thrust perfectly represents the archetype of progress.

Faith in progress has played various functions in society and in American history textbooks. The faith has promoted the status quo in the most literal sense, for it proclaims that to progress we must simply do more of the same. This belief has been particularly useful to the upper class, because Americans could be persuaded to ignore the injustice of social class if they thought the economic pie kept getting bigger for all. The idea of progress also fits in with social Darwinism, which implies that the lower class is lower owing to its own fault. Progress as an ideology has been intrinsically antirevolutionary: because things are getting better all the time, everyone should believe in the system. Portraying America so optimistically also helps textbooks withstand attacks by ultrapatriotic critics in Texas and other textbook adoption states.

Internationally, referring to have-not countries as “developing nations” has helped the “developed nations” avoid facing the injustice of worldwide stratification. In reality “development” has been making Third World nations poorer, compared to the First World. Per capita income in the First World was five times that in the Third World in 1850, ten times in 1960, and fourteen times by 1970. It’s tricky to measure these ratios, partly because a dollar buys more in the Third World than in the First, but per capita income in the First World is now twenty to sixty times that in the Third World.9 The vocabulary of progress remains relentlessly hopeful, however, with regard to the “undeveloped.” As economist E. J. Mishan put it, “Complacency is suffused over the globe, by referring to these destitute and sometimes desperate countries by the fatuous nomenclature of ‘developing nations.”10 In the nineteenth century, progress provided an equally splendid rationale for imperialism. Europeans and Americans saw themselves as performing governmental services for and utilizing the natural resources of natives in distant lands, who were too backward to do it themselves.

Gradually the archetype of progress has been losing its grip. In the last quarter-century the intellectual community in the United States has largely abandoned the idea. Opinion polls show that the general public, too, has been losing its faith that the future is automatically getting better. Reporting this new climate of opinion, the editors of a 1982 symposium entitled “Progress and Its Discontents” put it this way: “Future historians will probably record that from the mid-twentieth century on, it was difficult for anyone to retain faith in the idea of inevitable and continuing progress.”11

Probably not even textbook authors still believe that bigger is necessarily better. No one celebrates higher populations.12 Today, rather than boast of our consumption, we are more likely to lament our waste, as in this passage by Donella H. Meadows, coauthor of The Limits to Growth: “In terms of spoiling the environment and using world resources, we are the world’s most irresponsible and dangerous citizens.” Each American born in the 1970s will throw out ten thousand no-return bottles and almost twenty thousand cans while generating 126 tons of garbage and 9.8 tons of particulate air pollution. And that’s just the tip of the trashberg, because every ton of waste at the consumer end has also required five tons at the manufacturing stage and even more at the site of initial resource extraction.13

In some ways, bigger still seems to equal better. When we compare ourselves to others around us, having more seems to bring happiness, for earning a lot of money or driving an expensive car implies that one is a more valued member of society. Sociologists routinely find positive correlations between income and happiness. Over time, however, and in an absolute sense, more may not mean happier. Americans believed themselves to be less happy in 1970 than in 1957, and still less happy by 1998, yet they used much more energy and raw materials per capita in 1998.14

The 1973 oil crisis precipitated the new climate of opinion, for it showed America’s vulnerability to economic and even geological factors over which we have little control. The new pessimism was exemplified by the enormous popularity of that year’s ecocidal bestseller, The Limits to Growth.15 Writing the next year, Robert Heilbroner noted the new pessimism: “There is a question in the air... ‘Is there hope for man?”16 Robert Nisbet, who thinks that the idea of progress “has done more good over a 2500-year period... than any other single idea in Western history,”17 nonetheless agrees that the idea is in twilight. This change did not take place all at once. Intellectuals had been challenging the idea of progress for some time, dating back to The Decline of the West, published during World War I, in which Oswald Spengler suggested that Western civilization was beginning a profound and inevitable downturn.18 The war itself, the Great Depression, Stalinism, the Holocaust, and World War II shook Western belief in progress at its foundations.

Developments in social theory further undermined the idea of progress by making social Darwinism intellectually obsolete. Modern anthropologists no longer believe that our society is “ahead of” or “fitter than” so-called “primitive” societies. They realize that our society is more complex than its predecessors but do not rank our religions higher than “primitive” religions or consider our kinship system superior. Even our technology, though assuredly more advanced, may not be better in that it may not meet human needs over the long term.19

Another key justification for our belief in progress had come from biological theory. Biologists used to see natural evolution as the survival of the fittest. By 1973, a much more complex view of the development of organisms had swept the field. “Life is not a tale of progress,” according to Stephen Jay Gould.” “It is, rather, a story of intricate branching and wandering, with momentary survivors adapting to changing local environments, not approaching cosmic or engineering perfection.”20

Since textbooks do not discuss ideas, it is no surprise that they fail to address the changes in American thinking resulting from World War I, World War II, the Holocaust, or Stalinism, let alone from developments in anthropological or biological theory. By 1973, however, another problem with progress was becoming apparent: the downside risks of our increasing dominance over nature. Environmental problems have grown more ominous every year.

In the 1980s and 1990s, most books at least mentioned the energy crises caused by the oil embargo of 1973 and the Iran-Iraq War in 1980. No worries, however: textbook authors implied that both crises found immediate solutions. “As a result” of the 1973 embargo, Triumph of the American Nation told us, “Nixon announced a program to make the United States independent of all foreign countries for its energy requirements by the early 1980s.” Ten pages later, in response to gas rationing in 1979, “Carter set forth another energy plan, calling for a massive program to develop synthetic fuels. The long-range goal of the plan was to cut importation of oil in half.” No mention in 1979 of Nixon’s 1973 plan, which had failed so abjectly that our dependence on foreign oil, had spiraled upward, not downward.21 No mention that Congress never even passed most of Carter’s 1979 plan, inadequate as it was. Virtually all the textbooks adopted this trouble-free approach. “By the end of the Carter administration, the energy crisis had eased off,” Land of Promise reassured its readers. “Americans were building and buying smaller cars.” “People gradually began to use less gasoline and conserve energy,” echoes The American Tradition.

If only it were that simple! Between 1950 and 1975 world fuel consumption doubled, oil and gas consumption tripled, and the use of electricity grew almost sevenfold.22 Since then things have only grown worse. Meanwhile, world oil production has reached a plateau, as M. K. Hubbert predicted it would decades ago. In 1994 I wrote, “If our sources of energy are not infinite, which seems likely since we live on a finite planet, then at some point we will run up against shortages.” By 2007 these shortages have begun to manifest themselves, and the dislocations will prove enormous. A century ago farming in America was energy self-sufficient: livestock provided the fertilizer and tillage power, farm families did the work of planting and weeding, wood-heated the house, wind pumped the water, and photosynthesis grew the crops. Today American farming relies on enormous amounts of oil, not only for tractors and trucks and air-conditioning but also for fertilizers and herbicides. Given these circumstances, most social and natural scientists concluded from the 1973 energy crisis that we cannot blithely maintain our economic growth forever. “Anyone having the slightest familiarity with the physics of heat, energy, and matter,” wrote Mishan in 1977, “will realize that, in terms of historical time, the end of economic growth, as we currently experience it, cannot be that far off.”23 This is largely because of the awesome power of compound interest. Economic growth at 3 percent, a conventional standard, means that the economy doubles every quarter-century, typically doubling society’s use of raw materials, expenditures of energy, and generation of waste.

The energy crises of 1973 and 1979 pointed to the difficulty that capitalism, a marvelous system of production, was never designed to accommodate shortage. For demand to exceed supply is supposed to be good for capitalism, leading to increased production and often to lower costs. Oil, however, is not really produced but extracted. In a way, it is rationed by the oil companies and OPEC from an unknown but finite pool. Thus, the oil companies, which we habitually perceive as competing capitalist producers, might more accurately be viewed as keepers of the commons.

America has seen commons problems before. Imagine a colonial New England town in which each household kept a cow. Every morning, a family member would take the cow to the common town pasture, where it would join other cows and graze all day under the supervision of a cowherd paid by the town. An affluent family might benefit from buying a second cow; any excess milk and butter they could sell to cowless sailors and merchants. Expansion of this sort could go on only for a finite period, however, before the common pasture was hopelessly overgrazed. What was in the short-term interest of the individual family was not in the long-term interest of the community. If we compare contemporary oil companies with cow-holding colonial families, we see that new forms of governmental regulations, analogous to the regulated use of the commons, may be necessary to assure there will be a commons—in this case, an oil pool—for our children.24

The commons issue affects our society in other ways. Fishing and shellfishing are in crisis. A catch of 20 million bushels of crabs and oysters in Chesapeake Bay in 1892 and 3.5 million in 1982 fell to just 166,000 bushels in 1992. Fisherfolk responded the way people usually do when their standard of living is imperiled: work harder. This meant redoubling their efforts to take more of the few crabs and oysters still out there. Although this tactic may benefit an individual family, it cannot but wreak disaster on the commons. By 2006, scientists estimated that one-fifth of the fishing and oystering fleet in the bay would reap about the same harvest, with much less ecological damage. The problem of the bay is amplified in the oceans by the use of increasingly sophisticated fishing technology. A report in Science in 2006 predicted that 90 percent of all species of fish and shellfish that now feed people may be gone by 2048. Twenty-nine percent of those species have already collapsed, meaning that their harvests were already less than one-tenth what they had been. The United Nations is struggling to develop a global system “to manage and repropagate the fish that are still left.” Since international waters are involved, however, negotiations may not succeed until after many species have been made extinct.25

Because the economy has become global, the commons now encompasses the entire planet. If we consider that around the world humans owned ten times as many cars in 1990 as in 1950, no sane observer would predict that such a proportional increase could or should continue for another forty years.26 According to Jared Diamond, in 2005 the average American consumed thirty- two times as much of the world’s largesse and produced thirty-two times as much pollution as the average Third World citizen.27 Our continued economic development coexists in some tension with a corollary of the archetype of progress: the notion that America’s cause is the cause of all humankind. Thus, our economic leadership is very different from our political leadership. Politically, we can hope other nations will put in place our forms of democracy and respect for civil liberties. Economically, we can only hope other nations will never achieve our standard of living, for if they did, the earth would become a desert. Economically, we are the bane, not the hope of the world. Since the planet is finite, as we expand our economy we make it less likely that less developed nations can expand theirs. Today, increasing demand for fuel for Chinese vehicles is already creating a worldwide oil shortage.

Almost every day brings new reasons for ecological concern, from deforestation at the equator to ozone holes at the poles. Cancer rates climb and we don’t know why.28 We have no way even to measure the full extent of human impact on the earth. The average sperm count in healthy human males around the world has dropped by nearly 50 percent over the past fifty years. If environmentally caused, this is no laughing matter, for sperm have only to decline in a straight line for another fifty years and we will have wiped out humankind without even knowing how we did it.29

We were similarly unaware for years that killing mosquitoes with DDT was wiping out birds of prey around the globe. Our increasing power makes it increasingly possible that humankind will make the planet uninhabitable by accident. Indeed, we almost have, on several occasions. In the early 1990s, for example, nations around the planet agreed to stop production of many CFCs (chlorofluorocarbons) that damaged the ozone in the upper atmosphere. In 2006 Washington Post writer Joel Achenbach noted, “Scientists are haunted by the realization that if CFCs had been made with a slightly different type of chemistry, they’d have destroyed much of the ozone layer over the entire planet.”30 We were simply lucky.

All these considerations imply that more of the same economic development and nation-state governance that brought us this far may not guide us to a livable planet in the long run. We do not simply face an energy crisis that might be solved if we only develop a low-cost form of energy that does not pollute or cause global warming. On the contrary, if we had cheaper energy, imagine the havoc we might cause! Scientists have already envisioned how we could happily use it to decrease the salinity of the seas, increase our arable land, and in other ways make our planet nicer for us—in the short run. Instead, we must start treating the earth as if we plan to stay here. At some point in the future, perhaps before readers of today’s high school textbooks pass their fiftieth birthdays, industrialized nations, including the United States, may have to move toward steady-state economies in their consumption of energy and raw materials. Thus, our oil crisis can best be viewed as a wake-up call to change our ways.

Getting to zero economic growth involves another form of the problem of the commons, however, for no country wants to be first to achieve a no-growth economy, just as no individual family finds it in its interest to stop with one cow. A new international mechanism may be required, one hard even to envision today. Heilbroner is pessimistic: “No substantial voluntary diminution of growth, much less a planned reorganization of society, is today even remotely imaginable.”31 If, tomorrow, citizens must imagine diminished growth, we cannot rest easily, knowing that most high school history courses do nothing whatever to prepare Americans of the future to think imaginatively about the problem. Continued unthinking allegiance to the idea of progress in our textbooks can only be a deterrent, blinding students to the need for change, thus making change that much more difficult. David Donald characterizes the “incurable optimism” of American history courses as “not merely irrelevant but dangerous.”32 In this sense, our environmental crisis is an educational problem to which American history courses contribute.

Edward O. Wilson divides those who write on environmental issues into two camps: environmentalists and exceptionalists.33 Most scholars and writers, including Wilson, are of the former persuasion. On the other side stand a relative handful of political scientists, economists, and natural scientists, several associated with right-wing think tanks, who have mounted important counter-arguments to the doomsaying environmentalists. In 1994 I pointed to Julian Simon, Herman Kahn, and some others who compared their world to the world of our ancestors and argued that although modern societies have more power to harm the planet, they also have more power to set the environment right. After all, environmental damage has been undone on occasion. Some American rivers that were deemed hopelessly polluted forty years ago are now fit for fish and human swimmers. Human activity has reforested South Korea.34 Hence, the exceptionalists claimed, modern technology may exempt us from environmental pressures. They noted that recovery time after natural disasters such as earthquakes or man-made disasters such as World War II has become much shorter today than in the nineteenth century, owing in part to the ability of our large bureaucratic organizations to mobilize information and coordinate enormous undertakings. Human life expectancy, one measure of the quality of life, continues to lengthen. Herbert London, who titled his book Why Are They Lying to Our Children? because he believes that teachers and textbooks overemphasize the perils of economic growth, pointed out that more food was available in 1990 than twenty years earlier.35 Simon pointed out how most short-term predictions of shortages in everything from whale oil in the last century to silver in the 1990s have been confuted by new technological developments36. To be sure, higher prices will eventually make it profitable to use extraordinary measures—steam pressure and the like—to extract more oil.

In 1994 I faulted textbooks for not supplying students with either side of this debate and then encouraging them to think about it. Not only did the books ignore the looming problems, they also did not present the adaptive capacities of modern society. Authors should have shown trends in the past that suggest we face catastrophe and other trends that suggest solutions. Doing so would encourage students to use evidence from history to reach their own conclusions. Instead, authors assured us that everything will come out right in the end, so we need not worry much about where we are going.37 Their endorsement of progress was as shallow as General Electric’s, a company that claims, “Progress is our most important product,” but whose ecological irresponsibility has repeatedly earned it a place on Fortune’s list of the ten worst corporate environmental offenders.38

No longer do I suggest this evenhanded approach. Even though Simon is right and capitalism is supple, in at least two ways our current crisis is new and cannot be solved by capitalism alone. First, we face a permanent energy shortage, only beginning with an oil shortage. Such a shortage leads toward oligopoly—a “natural” cartel, not a forced cartel such as John D. Rockefeller achieved with Standard Oil around 1900—and cartels are not good capitalism. If a handful of companies controlled the manufacture of skis, so they could get together and charge whatever they wanted, someone might start another company not bound by their agreement or develop new, cheaper materials for skis or invent the snowboard—or we the public could stop buying skis. But if a handful of companies or countries control the oil industry, no new producer can break-in. Moreover, no alternative can easily be developed for petroleum in transportation.

Second, our use of oil (and all other fossil fuels) has a serious worldwide impact: global warming. As everyone now knows, except some high school history textbook authors, this warming melts the polar ice caps, causing sea levels to rise. Oceans rose one foot in the last century. The most conservative estimate, embraced by the George W. Bush administration, predicts they will rise another three feet in this century. Around the world—from Miami to Venice to much of Bangladesh—hundreds of millions of people live close enough to sea level that this rise will endanger their lives and occupations. The resulting dislocation will constitute the biggest crisis mankind has faced since the beginning of recorded history. And this is the most pleasant estimate. If the Greenland ice sheet melts, the oceans may rise twenty-three feet. Scientist James Lovelock in 1970 famously invented the “Gaia hypothesis,” the idea that the earth acts as a homeostatic system. Recently Lovelock has pointed out that as the earth’s equilibrium gets disturbed, some disequilibrium processes may cause even faster warming. As the polar ice caps melt, for example, they no longer reflect the sun’s rays, so the earth absorbs still more heat. Lovelock predicts the death of billions of people before equilibrium is established once more. Global warming also increases other weather problems: the average windspeeds of hurricanes have doubled in the past thirty years, and they are also more frequent.39

That’s not all. Evidence shows that carbon dioxide, a normal result of burning oil or coal, also makes the oceans more acidic. Scientists warn that, by the end of this century, this acidity could decimate coral reefs and kill off creatures that undergird the sea’s food chain. “It’s the single most profound environmental change I’ve learned about in my entire career,” said Thomas Lovejoy, author of Climate Change and Biodiversity. “What we’re doing in the next decade will affect our oceans for millions of years,” said Ken Caldeira, oceanographer at Stanford University.40

In addition to our energy and global-warming crises, we face other severe problems. Thousands of species face imminent extinction. One list of likely candidates includes a third of all amphibians, a fourth of the world’s mammals, and an eighth of its birds. Wilson thinks the foregoing is optimistic and believes two-thirds of all species will perish before the end of the century. Nuclear proliferation poses another threat. In 1945 only one country—the United States —had the know-how and economic means to build nuclear weapons. Since then, Great Britain, the USSR, France, China, India, Pakistan, Israel, South Africa, and apparently North Korea have joined the nuclear club. If Pakistan and North Korea can do it, clearly almost every nation on earth—and some private organizations, including terrorist groups—has the capability. The United States came uncomfortably close to using nuclear weapons in Vietnam in 1969, and India and Pakistan came uncomfortably close to using them against each other in 2002.41

In the long run, just keeping to the old paths regarding all these new problems is unlikely to work. “From the mere fact that humanity has survived to the present, no hope for the future can be salvaged,” Mishan noted. “The human race can perish only once.”42 If the arguments in this new edition of this chapter seem skewed to favor the environmentalists, perhaps the potential downside risk if they are right, as well as the ominous developments since the first edition, make this bias appropriate. After all, history reveals many previously vital societies, from the Mayans and Easter Island to Haiti and the Canaries that irreparably damaged their ecosystems.43 “Considering the beauty of the land,” Christopher Columbus wrote on first seeing Haiti, “there must be gain to be got.” Columbus and the Spanish transformed the island biologically by introducing diseases, plants, and livestock. The pigs, hunting dogs, cows, and horses propagated quickly, causing tremendous environmental damage. By 1550 the “thousands upon thousands of pigs” in the Americas had all descended from the eight pigs that Columbus brought over in 1493. “Although these islands had been, since God made the earth, prosperous and full of people lacking nothing they needed,” a Spanish settler wrote in 1518, after the Europeans’ arrival “they were laid waste, inhabited only by wild animals and birds.”44 Later, sugarcane monoculture replaced gardening in the name of quick profit, thereby impoverishing the soil. More recently, population pressure has caused Haitians and Dominicans to farm the island’s steep hillsides, resulting in erosion of the topsoil. Today this island ecosystem that formerly supported a large population in relative equilibrium is in far worse condition than when Columbus first saw it. This sad story may be a prophecy for the future, now that modern technology has the power to make of the entire earth a Haiti.

Not one textbook brings up the whale oil lesson, the Haiti lesson, or any other inference from the past that might bear on the question of progress and the environment. In sum, although this issue may be the most important of our time, no hint of its seriousness seeps into our history textbooks. To my surprise, today’s textbooks have actually gotten worse than their predecessors about the environment. Except for two passages in Pageant and one in Journey, they say nothing about environmental issues since the Carter presidency. The 1970 invention of Earth Day, 1973 Arab oil embargo, and 1979 Iran hostage crisis are the environmental events that get into our textbooks, along with the establishment of the Environmental Protection Agency during the Nixon administration. Fifteen more years have passed since these events took place. Since authors take no note of underlying trends but only of flashy events, they see no history to report in the interval. Putting the energy crisis that much further back in time, however, implies that it’s old news. Moreover, the textbooks imply that it has pretty much been fixed. “With the help of the [National Energy] act,” The Americans assures us in a typical passage, “U.S. dependence on foreign oil had eased slightly by 1979.” If so, 1979 was unusual, because in 1975, before Carter became president, the United States imported 35 percent of its petroleum, while in 2005 we imported 58 percent.

To expect textbooks published around 1990 to treat global warming might not be fair. In Atlantic Monthly in 2006, Gregg Easterbrook noted that it had not been proven:

Fifteen years ago, a thoughtful person looking at global-warming studies might have focused on the uncertainty; at that time the National Academy of Sciences itself emphasized uncertainty. Today a thoughtful person, who looks at recent science, including recent National Academy of Sciences statements, must deduce there is a danger.

Easterbrook described himself as “skeptical,” then “gradually persuaded by the evidence. Inuits living in the Arctic strongly agree; they warn that the entire ecosystem there is in collapse. Every year between 1997 and 2005 was one of the ten hottest ever recorded; 2005 set a record.”45

So how do today’s textbooks treat what may be the most important single issue of our time? Here is every word on the subject in all six textbooks, except for a passage at the very end of Pageant that we will analyze at the end of this chapter:

At the outset of the 21st century, developments like global warming served dramatic notice that planet earth was the biggest ecological system of them all—one that did not recognize national boundaries. Yet while Americans took pride in the efforts they had made to clean up their own turf, who were they, having long since consumed much of their own timberlands, to tell the Brazilians that they should not cut down the Amazon rain forest?

- The American Pageant

class="uk-margin-large-justify"Although no one is sure what causes global warming, a United Nations report warned that air pollution could be a factor.

The American Journey

Here Pageant implies that Third World countries form the bulk of the problem, although the United States contributes almost 25 percent of all CO2 emissions, far more than any other nation. Journey hedges: air pollution “could be a factor.” And four books never mention the subject.46

Why are textbook treatments of environmental issues so feeble? If authors revised their closing pages to jettison the unthinking devotion to progress, their final chapters would sit in uneasy dissonance with earlier chapters. Their tone throughout might have to change. From their titles on, American history textbooks are celebratory, and the idea of progress legitimates the celebration. Textbook authors present our nation as getting ever better in all areas, from race relations to transportation. The traditional portrayal of Reconstruction as a period of Yankee usurpation and Negro debauchery fits with the upward curve of progress, for if relations were bad in Reconstruction, perhaps not as bad as in slavery but surely worse than what came later, then we can imagine that race relations have gradually been getting better. However, the facts about Reconstruction compel us to acknowledge that in many ways race relations in this country have yet to return to the point reached in, say, 1870. In that year, to take a small but symbolic example, A. T. Morgan, a white state senator from Hinds County, Mississippi, married Carrie Highgate, a black woman from New York, and was reelected.47 Today this probably could not happen, not in Hinds County, Mississippi, or in many counties throughout the United States. Nonetheless, the archetype of progress prompts many white Americans to conclude that black Americans have no legitimate claim on our attention today because the problem of race relations has surely been ameliorated.48

A. T. Morgan’s marriage is hard for us to make sense of, because Americans have so internalized the cultural archetype of progress that by now we have a built-in tendency to assume that we are more tolerant, more sophisticated, more, well, progressive than we were in the past. Even a trivial illustration—Abraham Lincoln’s beard—can teach us otherwise. In 1860 a clean-shaven Lincoln won the presidency; in 1864, with a beard, he was reelected. Could that happen nowadays? Today many institutions, from investment banking firms to Brigham Young University, are closed to white males with facial hair. No white presidential candidate or successful Supreme Court nominee has ventured even a mustache since Tom Dewey in 1948. Beards may not in themselves be signs of progress, although mine has subtly improved my thinking, but we have reached an arresting state of intolerance when the huge Disney Corporation, founded by a man with a mustache, will not allow any employee to wear one. On a more profound note, consider that Lincoln was also the last American president who was not a member of a Christian denomination when taking office. Americans may not be becoming more tolerant; we may only think we are. Thus, the ideology of progress amounts to a chronological form of ethnocentrism.

Not only does the siren song of progress lull us into thinking that everything now is more “advanced,” it also tempts us to conclude that societies long ago were more primitive than they may have been. Progress underlies the various unilinear evolutionary schemes into which our society used to classify peoples and cultures: savagery-barbarism-civilization, for example, or gathering-hunting- horticultural-agricultural-industrial. Under the influence of these schemes, scholars completely misconceived “primitive” humans as living lives that, as Hobbes put it, were “nasty, brutish, and short.” Only “higher” cultures were conceived of as having sufficient leisure to develop art, literature, or religion.

The United States was founded in a spirit of dominion over nature. “My family, I believe, have cut down more trees in America than any other name!” boasted John Adams. Benjamin Lincoln, a Revolutionary War general, spoke for most Americans of his day when he observed in 1792, “Civilization directs us to remove as fast as possible that natural growth from the lands.” The Adams- Lincoln mode of thought did make possible America’s rapid expansion to the Pacific, the Chicago school of architecture, and Henry Ford’s assembly line. Our growing environmental awareness casts a colder light on these accomplishments, however. Since 1950 more than 25 percent of the remaining forests on the planet have been cut down. Recognizing that trees are the lungs of the planet, few people still think that this represents progress.

Anthropologists have long known better. “Despite the theories traditionally taught in high school social studies,” pointed out anthropologist Peter Farb, “the truth is, the more primitive the society, the more leisured its way of life.”49 Thus “primitive” cultures were hardly “nasty.” As to “brutish,” we might recall the comparison of the peaceful Arawaks on Haiti and the Spanish conquistadors who subdued them. “Short” is also problematic. Before encountering the diseases brought by Europeans and Africans, many people in Australia, the Pacific islands, and the Americas probably enjoyed remarkable longevity, particularly when compared with European and African city dwellers. “They live a long life and rarely fall sick,” observed Giovanni da Verrazano, after whom the Verrazano Narrows and bridge in New York City are named.50 “The Indians be of lusty and healthful bodies not experimentally knowing the Catalogue of those health-wasting diseases which are incident to other Countries,” according to a very early New England colonist, who apparently ignored the recently introduced European diseases that were then laying waste the Native Americans. He reported that the Indians lived to “three-score, four-score, some a hundred years, before the world’s universal summoner cites them to the craving Grave.”51 In Maryland, another early settler marveled that many Indians were great-grandfathers, while in England few people survived to become grandparents.52 The first Europeans to meet Australian aborigines noted a range of ages that implied a goodly number lived to be seventy. For that matter, Psalm 90 in the Bible implies that thousands of years ago most people in the Middle East lived to be seventy: “The years of our lives are three score and ten, and if by reason of strength they be four score, yet is their labor sorrow...”53

Besides fostering ignorance of past societies, belief in progress makes students oblivious to merit in present-day societies other than our own. To conclude that other cultures have achieved little about which we need to know is a natural side effect of believing our society the most progressive. Anthropology professors despair of the severe ethnocentrism shown by many first-year college students. William A. Haviland, author of a popular anthropology textbook, says that in his experience the possibility that “some of the things that we aspire to today—equal treatment of men and women, to cite but one example—have in fact been achieved by some other peoples simply has never occurred to the average beginning undergraduate.”54 Few high schools offer anthropology courses, and fewer than one American in ten ever takes a college anthropology course, so we can hardly count on anthropology to reduce ethnocentrism. High school history and social studies courses could help open students to ideas from other cultures. That does not happen, however, because the idea of progress saturates these courses from Columbus to their final words. Therefore, they can only promote, not diminish, ethnocentrism. Yet ethnocentric faith in progress in Western culture has had disastrous consequences. People who believed in their society as the vanguard of the future, the most progressive on earth, have been all too likely to indulge in such excessive cruelties as the Pequot massacre, Stalin’s purges, the Holocaust, or the Great Leap Forward.

Rather than assuming that our ways must be best, textbook authors would do well to challenge students to think about practices from the American way of birth to the American way of death. Some elements of modern medicine, for instance, are inarguably more effective and based on far better theory than previous medicines. On the other hand, our “scientific” antigravity way of birth, which dominated delivery rooms in the United States from about 1930 to at least 1970, shows the influence of the idea of progress at its most laughable. The analogy for childbirth was an operation: the doctor anesthetized the mother and removed the anesthetized infant like a gall bladder.55 Even as late as 1992, only half of all women who gave birth in U.S. hospitals breast-fed their babies, even though we now know, as “primitive” societies never forgot, that human milk, not bovine milk or “formula,” is designed for human babies.56 If history textbooks relinquished their blind devotion to the archetype of progress, they could invite readers to assess technologies as to which have truly been progressive. Defining progress would itself become problematic. Alternative forms of social organization, made possible or perhaps even necessary by technological and economic developments, could also be considered. Today’s children may see the decline of the nation-state, for instance, because the problem of the planetary commons may force planetary decision-making or because growing tribalism may fragment many nations from within.57 The closing chapters of history textbooks might become inquiry exercises, directing students toward facts and readings on both sides of such issues. Surely such an approach would prepare students for their six decades of life after high school better than today’s mindlessly upbeat textbook endings.

Thoughtfulness about such matters as the quality of life is often touted as a goal of education in the humanities, but history textbooks sweep such topics under the brightly colored rug of progress. Textbooks manifest no real worries even about the environmental downside of our economic and scientific institutions. Instead, they stress the fortunate adequacy of our government’s reaction. Textbook authors seem much happier telling of the governmental response—mainly the creation of the Environmental Protection Agency—than discussing any continuing environmental problems. By far the most serious treatment of our future in any of the new textbooks is this passage on the next to last page of The American Pageant:

Environmental worries clouded the country’s future. Coal-fired electrical generating plants helped form acid rain and probably contributed to the greenhouse effect, an ominous warming of the planet’s temperature. The unsolved problem of radioactive waste disposal hampered the development of nuclear power plants. The planet was being drained of oil...

By the early twenty-first century, the once-lonely cries for alternative fuel sources had given way to mainstream public fascination with solar power and windmills, methane fuel, electric “hybrid” cars, and the pursuit of an affordable hydrogen fuel cell. Energy conservation remained another crucial but elusive strategy—much-heralded at the politician’s rostrum, but too rarely embodied in public policy...

Although hardly a wake-up call, at least those words raise the issues and do not imply that they are nothing to worry about.

Unfortunately, on the next page—its last page—Pageant blandly reassures: “In facing those challenges, the world’s oldest republic had an extraordinary tradition of resilience and resourcefulness to draw on.” Many students are not so easily reassured. According to a 1993 survey, children are much more concerned about the environment than are their parents.58 In the late 1980s about one high school senior in three thought that nuclear or biological annihilation will probably be the fate of all mankind within their lifetimes.59 “I have talked with my friends about this,” a student of mine wrote in her class journal. “We all agree that we feel as if we are not going to finish our adult lives.” A survey of high school seniors in 1999 found that almost half believed the “best years of the United States were behind us.”60 These students had all taken American history courses, but the textbooks’ regimen of positive thinking does not seem to have rubbed off on them. Students know when they are being conned. They sense that underneath the mindless optimism is a defensiveness that rings hollow. Or maybe they simply never reached the cheerful endings of their textbooks.

Probably the principal effect of the textbook whitewash of environmental issues in favor of the idea of progress is to persuade high school students that American history courses are not appropriate places to bring up the future course of American history.61 What is perhaps the key issue of the day will have to be discussed in other classes—maybe science or health—even though it is foremost a social rather than biological or health issue. Meanwhile, back in history class, there are blander, data-free assurances that things are getting better.

E. J. Mishan has suggested that feeding students rosy tales of automatic progress helps keep them passive, for it presents the future as a process over which they have no control.62 I don’t believe this is why textbooks end as they do, however. Their upbeat endings may best be understood as ploys by publishers who hope that nationalist optimism will get their books adopted. Moreover, they know that Republicans have descended from the party of Nixon—when they passed the Environmental Protection Act—to the party of George W. Bush, where big business, especially oil, directs our environmental and energy policies. In today’s political climate publishers may worry that to suggest that global warming or energy shortages are real threats may be taken as partisan Democratic history. Hence, they may lose adoptions.

Such happy endings in our history books really amount to concessions of defeat, however. By implying that no real questions about our future need be asked and no real thinking about trends in our history need be done, textbook authors concede implicitly that our history has no serious bearing on our future. We can hardly fault students for concluding that the study of history is irrelevant to their futures.

James W. Loewen, Lies My Teacher Told Me. The New Press, 2008.

Chapter 11. Progress is Our Most Important Product.

Notes

1 Senator Albert J. Beveridge, speech in the U.S. Senate, January 9, 1900, Congressional Record, 56th Congress 33 (Washington, D.C.: U.S. Government Printing Office, 1900).

2 Frances FitzGerald, Fire in the Lake (Boston: Atlantic-Little, Brown, 1972), 8.

3 E. J. Mishan, The Economic Growth Debate (London: George Allen and Unwin, 1977), 12.

4 Vine Deloria Jr., God Is Red (New York: Dell, 1983 [1973]), 290.

5 Thomas Jefferson quoted in Robert Nisbet, History of the Idea of Progress (New York: Basic Books, 1980), 198.

6 Jules Henry, Culture Against Man (New York: Random House, 1963), 16-17. Crawford Young quotes Indian leader Jawaharlal Nehru and sociologist Orlando Patterson, pointing out that Third World countries also bought into progress. See “Ideas of Progress in the Third World,” in Gabriel Almond et al., eds., Progress and Its Discontents (Berkeley and Los Angeles: University of California Press, 1982), 83.

7 According to the Advertising Council’s citizenship manual, Good Citizen, quoted in Stuart Little, “The Freedom Train” (Bloomington: Indiana University, c. 1990, typescript), 11.

8 Edward H. Carr, What Is History? (New York: Random House, 1961), 158, 166; see also Almond et al., eds., Progress and Its Discontents, xi. Some Americans have a contrary need to believe our society has been, on balance, a curse to humankind. Such thinking has alternative psychological and cultural payoffs, allowing believers to imagine themselves wiser, “lefter,” or more critical than their peers.

9 Carr, What Is History?, 116; L. S. Stavrianos, Global Rift (New York: Morrow, 1981), 38. In Why Are They Lying to Our Children? (New York: Stein and Day, 1984), 124, Herbert London argues that the gap between rich and poor nations is not widening. See also: Cliff DuRand, “Mexico-U.S. Migration: We Fly, They Walk,” talk at Morgan State University, 11/16/2005, at World Prout Assembly website, worldproutassembly.org/archives/2006/01/mexicous_migrat.html, 11/2006; Giovanni Arrighi, “The African Crisis,” New Left Review 15, 5/2002, newleftreview.org/?page=article&view=2387, 11/2006.

10 Mishan, The Economic Growth Debate, 116.

11 Almond et al., eds., Progress and Its Discontents, xi.

12 The Reagan and Bush administrations still maintained through the 1980s that there was no population crisis, even in the Third World, because larger populations created more opportunity for capitalist development. These statements were intended to appeal to antiabortion groups at home, however, not as serious analyses of the social structures of disadvantaged nations, whose leaders ridiculed the American position.

13 Donella H. Meadows, “A Look at the Future,” in Robin Clarke, ed., Notes for the Future (New York: Universe Books, 1976), 63; Donella H. Meadows, correspondence, 11/15/1993.

14 General Social Survey, “If you were to consider your life in general these days, how happy or unhappy would you say you are, on the whole...” webapp.icpsr.umich.edu/GSS/, 11/2006.

15 Donella H. Meadows et al., The Limits to Growth (New York: Universe Books, 1972, 2d ed., 1974).

16 Robert L. Heilbroner, An Inquiry into the Human Prospect (New York: Norton, 1974), 13.

17 Nisbet, History of the Idea of Progress, 8.

18 Oswald Spengler, The Decline of the West (New York: Modern Library, 1965).

19 Colin Turnbull, The Human Cycle (New York: Simon & Schuster, 1983), 21.

20 Stephen Jay Gould, Hen’s Teeth and Horse’s Toes (New York: Norton, 1983).

21 Oil imports in 1980 were 63 percent greater than in 1973, according to the Statistical Abstract of the United States: 1993 (Washington, D.C.: Bureau of the Census, 1993).

22 Mike Feinsilber and William B. Mead, American Averages (Garden City, NY: Doubleday, 1980), 277; see also Matthew Wald, “After 20 Years, America’s Foot Is Still on the Gas,” New York Times, 10/17/1993.

23 Mishan, The Economic Growth Debate, 53. See also Warren Johnson, The Future Is Not What It Used to Be (New York: Dodd, Mead, 1985), 22-24.

24 See Garrett Hardin, “The Tragedy of the Commons,” Science 162 (1968):1243-48; and Garrett Hardin and John Baden, eds., Managing the Commons (San Francisco: W. H. Freeman, 1977).

25 B. D. Ayres Jr., “Hard Times for Chesapeake’s Oyster Harvest,” New York Times, October 15, 1993; David E. Pitt, “U.N. Talks Combat Threat to Fishery,” New York Times, 7/25/1993; Pitt, “Despite Gaps, Data Leave Little Doubt That Fish Are in Peril,” New York Times, August 3, 1993; Elizabeth Weise, “90% of the Ocean’s Edible Species May Be Gone By 2048, Study Finds,” USA Today, 11/3/2006; Juliet Eilperin, “U.S. Attempting to Reshape Fishing Rules,”

Washington Post, October 8, 2006; Chesapeake Research Consortium. “Managed Fisheries of the Chesapeake Bay,” chesapeake.org/FEPManagedFisheries.pdf, 11/2006.

26 Noel Perrin, “Who Needs the World When You Have Cable?” New York Times Book Review, April 26, 1992.

27 Natural History Museum: “Seeds of Change” (exhibit, Smithsonian Institution, Washington, D.C., 1992); Richard A. Falk, This Endangered Planet (New York: Random House, 1971), 139; Jared Diamond, talk at Politics and Prose (Washington, D.C.) 1/18/2006.

28 See Barry Weisberg, Beyond Repair (Boston: Beacon, 1971), 9.

29 “Sperm Counts Drop Over 50 Years,” Facts on File 52, no. 2706 (10/1/1992): 743(1); Michael Castleman, “The Sperm Crisis,” Mother Earth News, no.83 (9/1983): 176-77. The best guess as to the cause of the sperm-count drop may be disposable diapers that are too tight and overheat the testicles. See, inter alia, Andrea Braslavsky, “Could Disposable Diapers Lead to Infertility?” at AT&T Worldnet, dailynews.att.net, 9/28/2000. That’s a relief!

30 Joel Achenbach, “The Tempest,” Washington Post Magazine, 5/28/2006, 24.

31 Heilbroner, An Inquiry into the Human Prospect, 133.

32 David Donald, quoted by Paul Gagnon, “Why Study History?” Atlantic, 11/1988, 46.

33 Еdward O. Wilson, “Is Humanity Suicidal?” New York Times Magazine, 5/30/1993, 24-29.

34 Clyde Haberman, “South Korea Goes from Wasteland to Woodland,” New York Times, 7/7/1985, 6E.

35 London, Why Are They Lying to Our Children? 53. London must not have read the endings of American history textbooks!

36 John Tierney, “Betting the Planet,” New York Times Magazine, 12/2/ 1990, 52-53, 75-81.

37 Jane Newitt makes this point in The Treatment of Limits-to-Growth Issues in U.S. High School Textbooks (Croton-on-Hudson, NY: Hudson Institute, 1982), 13. She also criticized textbooks for bias in favor of the limits-to-growth side of the debate, which I cannot confirm; the textbooks I examined do not really treat environmental issues as a serious matter.

38 Faye Rice, “Who Scores Best on the Environment?” Fortune (7/26/1993):122. See also Debra Chasnoff ’s film on General Electric, Deadly Deception (Boston: Infact, 1990). General Electric’s newer corporate mantra is “We Bring

Good Things to Life.”

39 Mike Tidwell, talk at Politics and Prose (Washington, D.C.): 8/30/2006; Bill McKibben, “How Close to Catastrophe?” New York Review of Books, 11/16/2006.

40> Juliet Eilperin, “Growing Acidity of Oceans May Kill Corals,” Washington Post, 7/5/2006.

41 “The Red List,” iucnredlist.org, as reported by Sam Cage, “16,000 Species Said to Face Extinction” Associated Press, 05/01/2006, cnn.netscape.cnn.com/news/story.jsp ; Jeremy Rifkin, “The Risks of Too Much City,” Washington Post, 12/17/2006; William Burr and Jeffrey Kimball, eds., “Nixon White House Considered Nuclear Options Against North Vietnam, Declassified Documents Reveal,” National Security Archive Electronic Briefing Book No. 195, gwu.edu/~nsarchiv/NSAEBB/NSAEBB195/index.htm (7/31/2006).

42 Mishan, The Economic Growth Debate, Ch. 8.

43 On the Mayans, see Allen Chen, “Unraveling Another Mayan Mystery,” Discover, 6/1987, 40-49; for the Canaries, see Alfred W. Crosby Jr., Ecological Imperialism (New York: Cambridge University Press, 1986), 80, 94-97.

44 Alfred W. Crosby Jr., “Demographics and Ecology,” 1990, typescript, citing Las Casas; John Varner and Jeanette Varner, Dogs of the Conquest (Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 1983), 19-20; Spanish letter quoted in Kirkpatrick Sale, The Conquest of Paradise (New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1990), 165.

45 Gregg Easterbrook, reply to letters about his “Some Convenient Truths,” Atlantic Monthly, 11/2006, 21; Gretel Ehrlich, “Last Days of the Ice Hunters?” National Geographic, 1/2006, 80, 84; Eugene Linden, “Why You Can’t Ignore the Changing Climate,” Parade, 6/25/2006, 4.

46 The Americans includes a two-page section, “The Conservation Controversy,” buried on pages 1122-23 in the midst of a two-page treatment of a mishmash of topics after the last chapter of the book. It seems fair to predict that no student will ever reach this section.

47 Lerone Bennett, Black Power U.S.A. (Baltimore: Penguin, 1969), 345-46.

48 But see Jonathan Kozol, Savage Inequalities (New York: Crown, 1991), 3.

49 Peter Farb, Man’s Rise to Civilization (New York: Avon, 1969), 49-50.

50 Verrazano quoted in Neal Salisbury, Manitou and Providence (New York: Oxford University Press, 1982), 26.

51 Quoted in Russell Thornton, American Indian Holocaust and Survival (Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 1987), 39

52 Karen Ordahl Kupperman, Settling with the Indians (London: J. M. Dent, 1980), 58.

53 Psalm 90, verse 10. See also S. Boyd Eaton et al., The Paleolithic Prescription (New York: Harper and Row, 1988); and Marshall Sahlins, Stone Age Economics (Chicago: Aldine and Atherton, 1972). There are statistical issues here, one being that average life expectancy at birth can be quite low if 40 percent of all newborns die in their first year, so a better measure is life expectancy at age one or age ten. Measuring life expectancy before European and African diseases is also not easy when those diseases accompanied and even antedated first contact. On the other hand, information from archaeology summarized by Jared Diamond in “The Worst Mistake in the History of the Human Race,” Discover, 5/1987, 64-66, suggests the early European settlers quoted above may have been too optimistic in their assessments of Indian longevity.

54 William A. Haviland, “Cleansing Young Minds, or What Should We Be Doing in the Introductory Course to Anthropology?” (paper presented at the annual meeting of the American Anthropology Association, New Orleans, 1990), 3.

55 Special instruments were developed for the operation, and the whole thing was done not only against the forces of nature but also uphill, against the force of gravity. We might contrast Las Casas’s description of birthing on Haiti before the arrival of Europeans: “Pregnant women work to the last minute and give birth almost painlessly; up the next day, they bathe in the river and are as clean and healthy as before giving birth.” (History of the Indies [New York: Harper and Row, 1971], 64).

56 “Harper’s Index,” Harper’s, 2/ 1993, 15, citing Ross Labs. Many hospitals still separate mothers and infants except for feeding time, even though scientific studies—which seem to be the only point of leverage for changing birthing practices—show that randomly selected neonatals raised with more parental contact have higher IQs. See Feinsilber and Mead, American Averages, 227-28.

57 Philip D. Curtin, The Rise and Fall of the Plantation Complex (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1990), esp. 35, gives an interesting analysis of the rise of the nation-state as a necessary response to the military might of neighboring nation-states. Curtin argues that in other ways nation-states were not necessarily advantageous for their citizens. If the need to control nuclear weapons leads to an era of relative peace in the next century, that may remove a primary reason for the power of the nation-state.

58 Ruth Bond, “In the Ozone, a Child Shall Lead Them,” New York Times, 1/10, /1993.

59 Daniel Evan Weiss, The Great Divide (New York: Poseidon, 1991), 136.

60 National Association of Secretaries of State New Millennium Survey, 1999, stateofthevote.org/New%20Mill%20Survey%20Update.pdf, 12/2006.

61 See Catherine Cornbleth, Geneva Gay, and K. G. Dueck, “Pluralism and Unity,” in Howard Mehlinger and O. L. Davis, eds., The Social Studies (Chicago: University of Chicago Press/NSSE Yearbook, 1981), 174.

62 E. J. Mishan, Pornography, Psychedelics, and Technology (London: George Allen and Unwin, 1980), 25, 150-51. See also Jonathan Kozol, The Night Is Dark and I Am Far from Home (Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1975), 40