Recovery of lost archaeological features on the Yalu River through GIS and historical imagery

Abstract

Urban development and other human-driven processes worldwide have destroyed archaeological remains in the process of reshaping the landscape, often before those remains have been properly analyzed. Under certain circumstances, however, some information regarding these lost remains is partially recoverable though the use of historical imagery produced before the development that destroyed the remains. Imagery from airborne or satellite platforms has been successfully exploited in various parts of the world, particularly in Europe, to recover archaeological information that had been presumed to be lost. Such utility of historical imagery is greatly enhanced when they are used within a GIS environment. The present study represents an initial exploration using historical imagery in a GIS environment to identify, map, and interpret lost archaeological remains in the Yalu River valley dividing China and Korea. The study centers on elite mortuary remains of the third to fifth centuries CE associated with the early kingdom of Koguryŏ (Ch. Gaogouli) in the Ji’an region of the Chinese province of Jilin. Analysis of satellite imagery from the 1960s along with aerial imagery from the Korean War (1950–53) and from U-2 overflights from the 1960s permits the recovery of information on hundreds of archaeological features in this region that have been lost to development, many of them having never been recorded. The present study focuses primarily on mortuary remains that have been completely or partially erased from the landscape and are here identified and described for the first time, with analysis that suggests how these lost remains can be understood in context with more recent archaeological findings. The results presented in this study offer a valuable methodology for recovering lost archaeological data and facilitate a deeper analysis of the mortuary practices associated with royal burials of Koguryŏ and of the use of space in the kingdom’s capital.

Introduction

The effectiveness of both aerial photography and geographic information systems (GIS) in archaeological research has been well demonstrated in recent decades. Used in combination these tools represent a powerful methodological advance that adds depth and function to research on archaeological sites and their context in the larger landscape. The use of historical imagery from aerial or satellite platforms further provides a window through which we may view archaeological landscapes that have been lost to urban development. The present study introduces the previously-unexplored use of historical imagery and GIS tools in an effort to reconstruct the archaeological landscape of the Ji’an region of northeastern China, an area that has seen rapid urban development in recent decades at the expense of the rich archaeological record that had survived until the twentieth century. Ji’an served as the capital of the ancient kingdom of Koguryŏ (first century BCE to 668 CE), and the abundant archaeological remains of that kingdom reflect the historical phase in which the polity developed into a powerful expansive state. Although most of the surviving archaeological features of Ji’an are now registered as protected cultural resources, urban development from the mid-twentieth century resulted in the destruction of many aboveground Koguryŏ remains, especially mounded tombs. This study illustrates how utilization of historical aerial imagery from 1950 to 1965 allows us to recreate the pre-development landscape of Ji’an and to recover much of the archaeological data that had been presumed lost. In the following I focus primarily on lost mortuary features that are here revealed for the first time, offering new archaeological information and suggesting ways in which these newly rediscovered features can be understood in context with more recent archaeological work conducted in Ji’an.

Ji’an: the isolated core of a kingdom

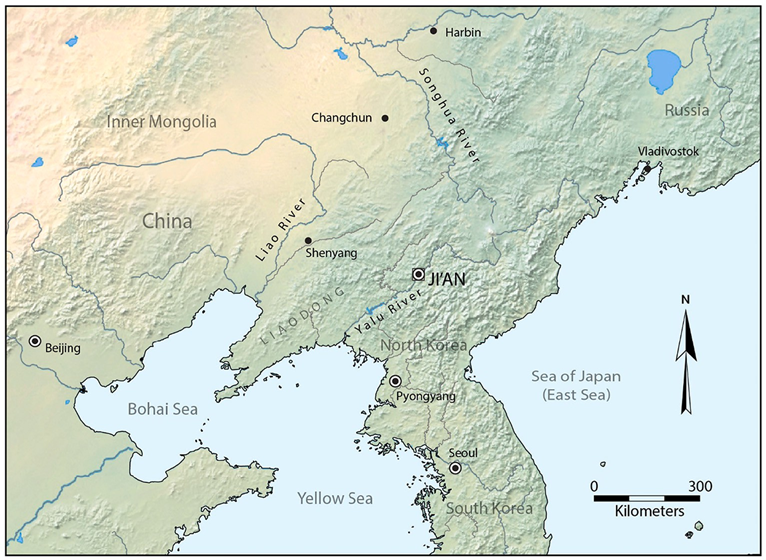

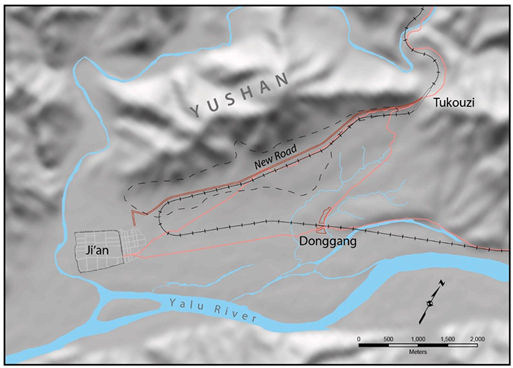

The small Chinese town of Ji’an in Jilin Province sits on the north bank of the Yalu River overlooking North Korea (Fig. 1). Until recent years the town had been relatively difficult to access, yet it has long drawn large numbers of tourists from other parts of China and abroad. This is largely due to the fact that Ji’an is home to a very large number of remains belonging to the ancient kingdom called Gaogouli in modern Chinese but better known in western scholarship through the modern Korean pronunciation of Koguryŏ (the name “Korea” can be traced back to “Koguryŏ”). At its height this kingdom, which existed from ca. first century BCE until its collapse in 668 CE, governed vast territories spanning what are today southern Manchuria, all of North Korea, and the northern part of South Korea. During its period of expansive development Koguryŏ’s rulers were based at Ji’an, which served as the kingdom’s capital from circa 200 CE until it was removed to Pyongyang in 427.

Ji’an’s location in a broad river plain surrounded by trackless mountain terrain made it an ideal place for the Koguryŏ capital at a time when the kingdom was under almost constant threat by the Chinese or Xianbei rulers of the Liaodong region to the west. The need for defense evidently outweighed the disadvantages such a remote and isolated location would have presented for transportation and distribution of goods. Nevertheless, the kingdom thrived in this location for over two centuries despite two devastating attacks, in 244 and 342, by neigh boring polities based in Liaodong, and about a dozen kings and their nobles were buried in monumental tombs that still impress visitors in Ji’an today. By the early fifth century Koguryŏ’s rulers, no longer requiring the defensive protection afforded by the Ji’an valley, shifted their focus southward and moved the capital city in 427 to modern Pyongyang, where it would remain until the kingdom fell in 668. During this late phase of Koguryŏ history, Ji’an served as a subsidiary capital, and many of the large tomb mounds there date to this period.

After the fall of Koguryŏ the Ji’an site continued to serve as an administrative base for a succession of states, though its importance never approached that which it enjoyed during the Koguryŏ period. Ji’an disappears from recorded history after the Mongols occupied the region in the thirteenth century, but it is likely that it lay in ruins for centuries, serving as a place of settlement only for very small populations of farmers and hunters. Once the territories of the Korean state of Chosŏn (1392–1910) had reached northward to the Yalu in the late fourteenth century, we find sporadic references to the ancient remains there, though by this time any connection with Koguryŏ had been lost. Although the north bank of the Yalu lay just beyond Chosŏn’s territories, the ancient remains were easily visible from the opposite shore and several literati observing those remains from afar were even moved to record their impressions in verse. After the Manchus overran Ming China and established the Qing empire in the mid-seventeenth century, most of Manchuria, including Ji’an, was considered a sacred ancestral land and was placed off limits to settlement, which is probably the reason the Koguryŏ remains there survived relatively unmolested for so many centuries.

Eventually, however, the Ji’an region was opened for development in the late nineteenth century as the easternmost part of the new Huairen administration, established in 1875 with its base in the modern town of Huanren. The new settlement at Ji’an was established within the walls of the ancient Koguryŏ city, and with the discovery in Ji’an of the King Kwanggaet’o stele around 1876, the site’s association with Koguryŏ was rediscovered. Early scholarly attention to Ji’an, then called Tonggou (though officially named Ji’an in 1902), was virtually monopolized by Japanese in connection with Japan’s territorial designs on both Korea and Manchuria. The records and photographs preserved from the visits by Torii Ryuzo, Sekino Tadashi, Ikeuchi Hiroshi, and Fujita Ryosaku, among others, remain an invaluable resource for the study of the archaeology of this region. Particularly important at this time was the publication of the two-volume Tsuko (or Tonggou) by Ikeuchi Hiroshi and Umehara Sueji in 1938 and 1940.

Ji’an underwent gradual development during the first half of the twentieth century, mostly under the Japanese-dominated Manchukuo state (1932–1945), during which time a railroad line was run through Ji’an, connecting central Manchuria with northern Korea (then under Japanese colonial occupation) via the town of Manp’o on the south bank of the Yalu. During the early phase of the Korean War (1950–1953), Ji’an became one of the primary bases for the dispatch of Chinese troops into northern Korea (Appleman, 1961:718, 756, 766), and it is likely that rapid development and preparation for war during 1950 and 1951 took a toll on the landscape as well as on the archaeological remains there. From the late 1950s and through the 1990s Chinese scholars engaged in archaeological studies of the Koguryŏ remains in and around Ji’an, with a notable lull in scholarly activity during the Cultural Revolution (1966–1976). From the 1960s, however, urban development picked up pace, and a number of archaeological remains appear to have been destroyed or damaged at this time.

In the early 2000s, considerable resources and effort were devoted to intensive archaeological survey and excavation in Ji’an in preparation for an application to UNESCO for inscription of the remains as World Heritage sites, which was approved in July 2004. Several valuable publications emerged from this work, representing the most detailed analysis of the archaeological remains of Ji’an yet to appear, far sur passing Ikeuchi’s work of the late 1930s. Since 2004, urban development has continued and intensified, and Ji’an has become a thoroughly modern Chinese town with a population of nearly 220,000.1 Although most of the surviving Koguryŏ remains have been designated as protected cultural resources, the effects of urban modernization have taken a toll on them, making the earlier studies and reports of these remains all the more important to research.

Koguryŏ mortuary remains in Ji’an

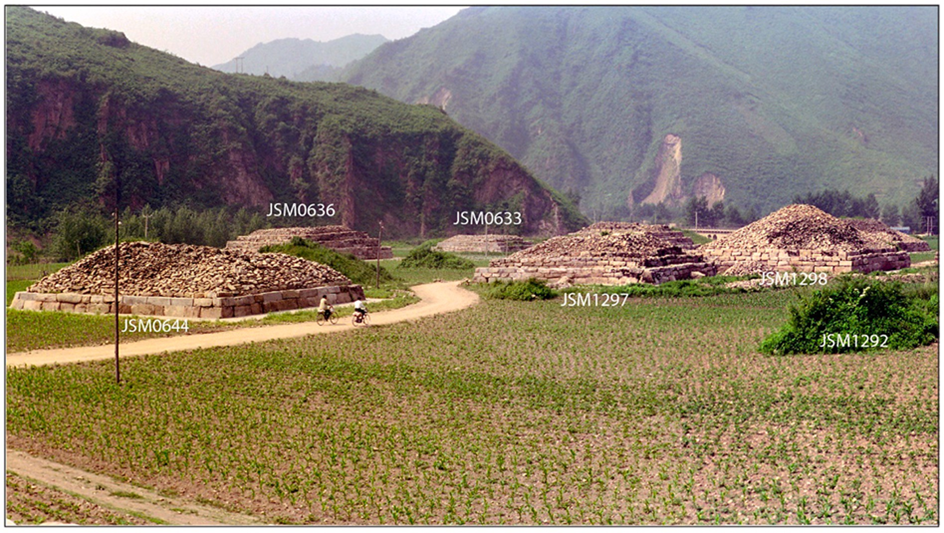

Koguryŏ remains in Ji’an fall into a number of categories, including walled sites, building and settlement features, monumental stelae, and mortuary remains. Of these, the last are by far the most numerous, and some of the tomb mounds were built on a massive scale. Tomb mounds are typically classified into two general types—those constructed entirely of stone and those covered by a mound of earth—though both types are in turn divided into a number of subtypes based on specific construction (Wei, 1994:84–87; Azuma, 2016:319–323). Stone mounded tombs take the form of cairns of rock or river stone, some of which have one or more rectangular base platforms constructed in tiers with the cairn on top (Fig. 2). Earlier stone tombs have burial chambers in the form of a shaft opening in the center of the top of the mound, while later ones have corridor-style side entrances leading to a tomb chamber. Earth-mounded tombs have corridor-style entrances and one or more burial chambers, some of which are richly decorated with painted murals (Fig. 3). The stone-mounded tombs are known to be the earlier form of burial, the transition to earth-mounded tombs spanning the late-fourth to early-fifth centuries (Wei, 1994:53–56). There is no way to estimate how many Koguryŏ tombs in Ji’an survived to the early twentieth century, but they would have numbered in the thousands. Many of these, the stone tombs in particular, would have succumbed early to new settlement, as they would have been disassembled and utilized as building material for new dwellings, a destructive process that continued throughout the twentieth century.

Fig. 1. Location of Ji’an on the Yalu River.

Fig. 2. Koguryŏ stone-mounded tombs in Ji’an.

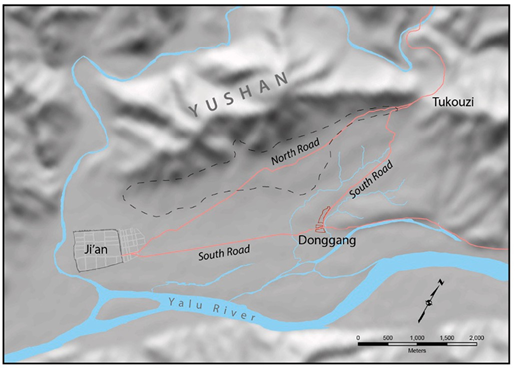

Another process that proved destructive to tombs in Ji’an was the construction of roads and, especially, the railroad. The primary northern route into the Ji’an plain runs through a place called Tukouzi in the northeastern part of the plain. Early roads from the north entered Ji’an in this location through a saddle gap where the elevation between mountains dips to a low point. The main road proceeded southward from this location toward what was the village of Donggang (now part of Taiwang township), while another smaller northern route ran along the lower slopes of Yushan (Yu Mountain) through a particularly dense concentration of tomb mounds (Fig. 4). The southern road to Donggang ran through an area largely free of tombs. Some tombs may have been cleared to make way for the northern road, but the early route seems to have wound around tomb clusters where possible. In the late 1930s a railroad was run through the plain roughly parallel to the northern road until it approached the old walled town, where it looped to run eastward in the lower part of the plain. The rail route required a broader clearance than did the older road, and it could not wind to avoid the tombs along its straight path. During his brief visit to Ji’an in 1938, the scholar Fujita Ryosaku observed the destruction wrought upon the tombs by the railroad construction then underway, by which time hundreds of tombs had been destroyed (Fujita, 1948:498). By the time the railroad construction was completed in 1939, many more tombs and other archaeological remains must have been lost. Fujita surveyed a number of surviving tombs and their environs and described them in his report (Fujita, 1948).

Fig. 3. Koguryŏ earth-mounded tombs in Ji’an.

Fig. 4. Locations in Ji’an. Dotted line indicates zone of dense concentration of tombs.

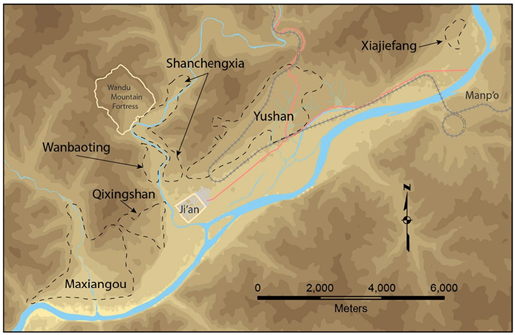

Fig. 5. Location of tomb clusters in Ji’an.

The first comprehensive survey of all tombs in the Ji’an region occurred in 1966 when over forty people were assigned to survey, classify, and register all surviving tombs over a period exceeding two months ending in June. At this time six distinct clusters of tombs were recognized in the area, and they were collectively referred to as the Donggou tomb cluster (Fig. 5). These clusters were those at Yushanxia (usually referred to as the Yushan cluster), Shanchengxia, Wanbaoting, Qixingshan, Maxiangou, and Xiajiefang. The 1966 survey resulted in a complete list of 10,782 tombs, which were displayed on a 1:2000-scale distribution map (Jilinsheng Wenwu Kaogu Yanjiusuo and Ji’anshi Bowuguan, 2002:9–10).2 Because this survey ended just as the Cultural Revolution was gaining momentum, the results were rarely utilized over the next decade, though additional small-scale surveys and excavations took place occasionally. In 1976 and 1979 additional surveys were conducted to update the register and correct errors as well as to account for tombs lost due to development since 1966. By 1984 surviving tombs in Ji’an numbered 7160 (Jilinsheng Wenwuzhi Bianweihui, 1984:100), indicating a loss of 3622 tombs since 1966.

Over two seasons in 1984 and 1985 large-scale excavations and surveys were conducted on 113 tombs in the Yushan cluster prior to their destruction in preparation for the construction of a new road leading to town running immediately to the north of and paralleling the railroad. This replaced the road to Donggang (Taiwang township) as the main route into Ji’an (Fig. 6). The lengthy report resulting from this work, representing the most comprehensive study of Koguryŏ tomb characteristics to that time, was published in 1993 (Jilinsheng Wenwu Kaogu Yanjiusuo and Ji’anshi Wenwu Baoguansuo, 1993). In 1997 a second comprehensive survey was conducted on all tombs in the Donggou cluster with the intent to correct omissions and errors in earlier registers and to create a better classification system and distribution diagram. The new register and distribution diagram (the latter in the form of 100 maps in 1:2500 scale) were published in bound form in 2002, providing an invaluable resource for the study of the surviving tombs in Ji’an (Jilinsheng Wenwu Kaogu Yanjiusuo and Ji’anshi Bowuguan, 2002). This volume includes a table providing data for each tomb, including its registry number, structure type, and physical dimensions. Surviving tombs catalogued in this survey numbered 6854, showing that some 3928 tombs had been destroyed since the 1966 survey. The associated maps show the approximate location of the tombs (indicating in dashed outlines the locations of now-lost tombs that had been included in the 1966 survey) as well as the structure type. The base maps provide contour lines indicating elevation in 2 m increments and show the locations of zones then (1997) occupied by buildings or settlements. The topographical features reflected in these maps represent the situation in the late 1990s, by which time the landscape had undergone significant alteration, a process that accelerated in the early 2000s.

In 2003 an application was submitted to UNESCO to have the more prominent Koguryŏ remains in Ji’an inscribed collectively as a World Heritage site, in preparation for which modern structures in the vicinity of large tombs and walled sites were cleared away and efforts were made to protect and preserve the surviving remains. Surveys and excavations were conducted on these sites, the results of which were published the following year in three volumes (Jilinsheng Wenwu Kaogu Yanjiusuo and Ji’anshi Bowuguan, 2004a, 2004b, 2004c). Today these remains are protected and are the focus of a thriving tourist industry in Ji’an. Although the publication of the archaeological data is invaluable for the study of these remains, there was little attempt made to describe the encroachment of modern development in their vicinity, which in some cases would have destroyed archaeological information. Based only on presently available materials, archaeologists would be unable to deter mine whether the absence of archaeological remains in the vicinity of the surviving features indicates that no such remains ever existed or that once-existing remains had been destroyed by modern development. That this is a real problem will be demonstrated shortly.

Fig. 6. Roads in Ji’an.

Recovering the pre-development landscape

As just described, the abundant above-ground remains of the Koguryŏ kingdom in Ji’an have been adversely affected by the increasing pace of modern urban development. Such development, along with historical circumstance and lack of documentation, has resulted in the loss of a great deal of information regarding the landscape and archaeological remains of Ji’an. Researchers appear to be resigned to the fact of this loss and generally consider the information to be unrecoverable. However, during the process of a larger-scale research project I am currently undertaking, I have found that a great deal of precise information regarding lost archaeological remains and the physical landscape of Ji’an can be recovered through the integrated use of various types of historical imagery in a Geographical Information Systems environment. Through these tools and resources, I have been able to document the locations of hundreds of now-lost Koguryŏ tombs and other remains, including some for which there appear to be no records at all. The same process makes possible the recovery of landscape information that cannot now be observed due to the reworking of land features through quarrying, the building of embankments, or the covering and rerouting of natural drainage channels. All of this recovered information can be of enormous use to the study of the archaeology and history of Ji’an, as I will shortly illustrate with a few examples.

Historical imagery of Ji’an is available in a variety of media and contexts and includes terrestrial, aerial, and satellite imagery. Some of the most useful examples of terrestrial imagery were produced by Japanese scholars roughly between 1910 and 1940.3 Such photographs reveal the features and landscape of Ji’an prior to the most destructive phase of urban development, but because their coverage is selective, they are less useful for comprehensive analysis of the region.

The majority of aerial imagery I have used is US reconnaissance photography dating to the early phase of the Korean War (primarily late 1950 and 1951) and consists of both vertical and oblique panchromatic imagery of Ji’an and its vicinity. Such images vary greatly in quality and coverage, but they are an invaluable resource as they provide very broad and continuous spatial coverage and reveal the features of Ji’an still largely unspoiled by development.4 Another type of aerial imagery that has proved to be exceedingly useful is declassified US reconnaissance imagery from U-2 overflights of China and North Korea dating from 1962 to 1965. Photographs from this context are useful in that the majority of missions (those using the Hycon Model B camera set to Mode I operation) provide very high resolution and horizon-to-horizon over lapping spatial coverage and that they typically present oblique views of Ji’an, which provide a helpful perspective in combination with the Korean War imagery, which offers mostly vertical views of Ji’an. To my knowledge, the aerial imagery from the Korean War and from U-2 overflights has not previously been extensively exploited for archaeological content in northeast Asia.

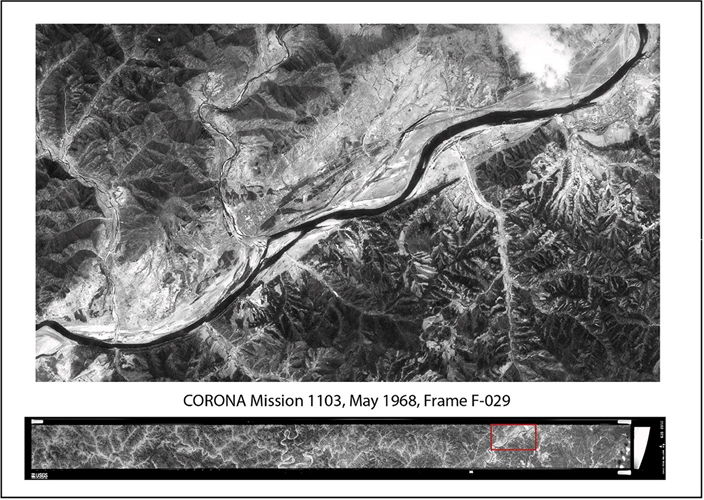

The most useful satellite imagery is the declassified US reconnaissance photography from CORONA satellites. Although typically lower in resolution than the aerial imagery described above, panchromatic CORONA images capture a very large geographic area in a single frame on long negative strips measuring 2.25 in. in width and about 30 in. in length.5 Although the mechanics of the panoramic scanning camera result in consistent distortions across the imaged swath, increasing with distance from the photographic center (Sohn et al., 2004), when a relatively small section of the total image is isolated, it can be treated as a single frame with only minor distortion (Casana and Cothren, 2008, 2013). Further, when the area of interest is near the center of the full negative frame (i.e., near the nadir), the isolated section provides an image with minimal orthographic distortion. Such qualities make CORONA images especially useful as base maps—once they are georeferenced based on recent orthorectified satellite images, they can be used as a basis for georeferencing the aerial imagery described above (this is often necessary due to the loss of recognizable landmarks visible in recent satellite images, making them unsuitable as a basis for georeferencing older aerial photographs).

Although such historical images have been available for some time, their utility in archaeological work had until recently been limited due to the lack of generally available GIS tools and to the fact that the images, CORONA imagery excepted, have been (and often continue to be) very difficult to access and to acquire in digital format. GIS is now a well- developed and expanding field, and its application in combination with overhead imagery in archaeological work has been abundantly demonstrated (Conolly and Lake, 2006; Hanson and Oltean, 2013; Comer and Harrower, 2013), including, most recently, the effective use of U-2 imagery in archaeology (Hammer and Ur, 2019). In East Asian context, CORONA satellite imagery has been effectively utilized in archaeological studies in recent years in China (Li, 2013; Hao and Moriya, 2017; Hu et al., 2017; Watanabe et al., 2017). Rather less frequently, historical aerial images taken prior to the 1970s have also been used in Chinese, Japanese, and Korean archaeological research, sometimes in conjunction with historical and more recent space-borne imagery (Shandongsheng Wenwu Kaogu Yanjiusuo, 2000; Sawada, 2002; Zhang and Wu, 2007; Sawada, 2011; Lasaponara et al., 2018; Yanaka, 2018; Hŏ, 2021; Hŏ and Yang, 2021). Studies utilizing aerial imagery in China have naturally tended to focus more on China’s central regions, as have archaeological studies in general. Certain of the peripheral areas, especially the border with North Korea, remain politically sensitive, limiting the possibilities of collecting new data from airborne remote sensing platforms. The most useful existing historical imagery for this border region is that produced by US overflights from the Korean War and by U-2 aircraft in the 1960s, yet this imagery, probably due to difficulty of access, has not to my knowledge been previously used for archaeological research, though such imagery often provides much better resolution than does that from CORONA.

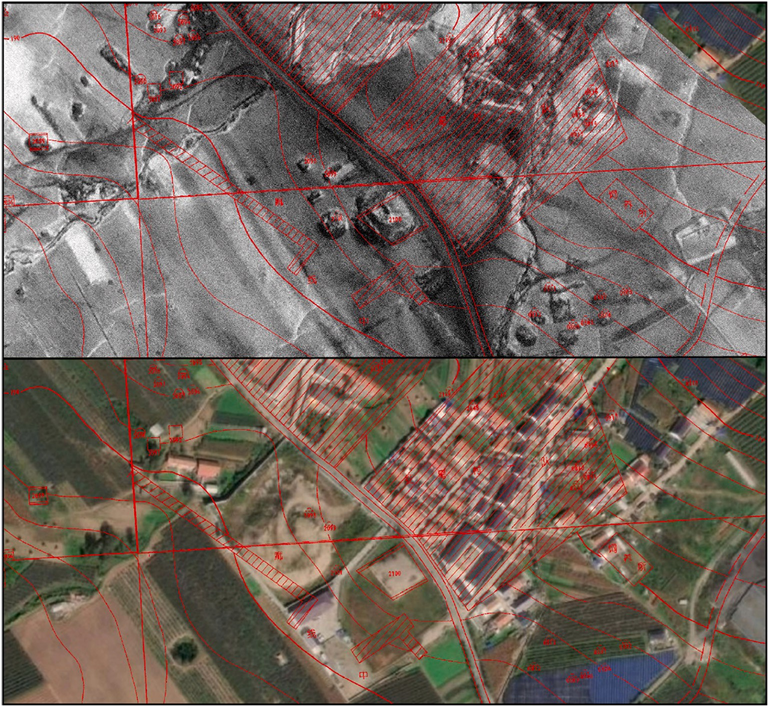

For the analysis that follows I have used ESRI’s ArcMap application as a base for georeferencing historical imagery and maps, making it possible to create multiple overlays allowing one to observe a given location through numerous points in time. For the Ji’an region I have found it useful first to georeference a section of a CORONA satellite image from the 1960s using ESRI’s orthorectified image basemap as a reference (Fig. 7), as this provides a helpful bridge when seeking control points for earlier aerial images (as noted above, extensive urban development makes it difficult to locate landscape features common between current and early historical imagery without the use of a chronologically intermediate base image as represented by the CORONA layer). The intermediate layer being established, I then utilized it in tandem with the ESRI basemap to georeference individual aerial images. I also georeferenced a number of historical maps of the Ji’an region, including the individual tiles of the 1:2500-scale maps generated by the 1997 survey. These layered images permitted me to identify above- ground archaeological features, including many that have been lost and still others that appear to be otherwise unknown. I compiled these features in a database with geocoded references, and when possible and desirable I also created associated shapefiles representing the visible surface outlines of the features.

In the following sections I will present a few representative examples of the usefulness of this method in recovering now-lost archaeological information that permits a deeper understanding of Koguryŏ mortuary practices and the spatial composition of its capital city.

Identifying royal tombs

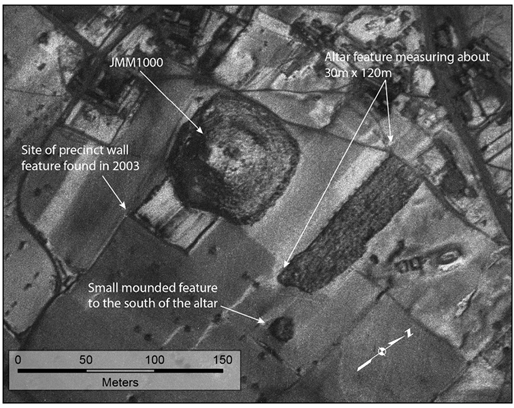

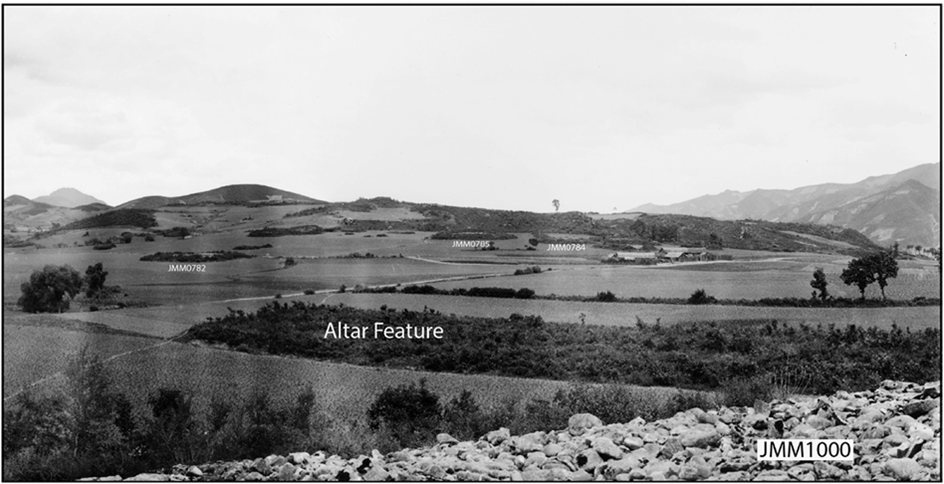

Historical records indicate that at least ten Koguryŏ rulers should have been buried in Ji’an, and I have elsewhere discussed the characteristics of Koguryŏ elite burials (Byington, 2019). Of a number of characteristics, including tomb size, marked precincts, and the use of tiled-roof structures on top of the tombs, the single factor that seems to have been reserved for the burials of kings is the inclusion of what archaeologists in Ji’an have called the ritual altar (jitan). Though the specific function of this feature is not known, it takes the form of a long rectangular platform made of piled stones positioned some distance (10 to 50 m) to the east or northeast of the tomb itself, which is always of the stone-piled variety (Fig. 8). There are some ten tombs in Ji’an for which ritual altar features have been clearly identified, and all of these tombs share other characteristics that seem to indicate royal interments, including their standing in isolation with no other tombs in their immediate vicinity.

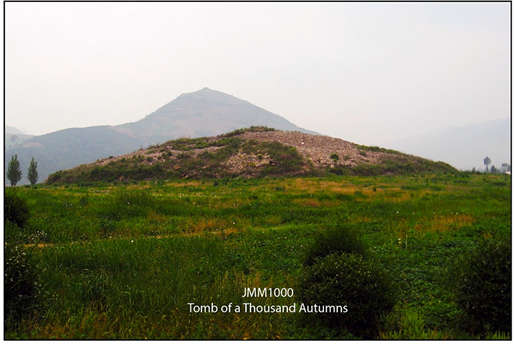

In my previous study I pointed out two additional tombs, both in the Maxian section of the Donggou tomb cluster, that are candidates for the list of royal burials despite their presently lacking clear evidence of altar structures. The first, registered as JMM1000 and popularly called the Tomb of a Thousand Autumns, is in all respects certainly the tomb of a king of the late fourth century, but the excavations conducted in 2003 yielded no evidence of an altar structure. The second tomb, JMM2100, is a likely candidate for a slightly earlier kingly burial, but the area in which we would expect to find an altar feature has long been occupied by a modern road and a residential area. The analysis of historical imagery provides useful information that helps to resolve lingering uncertainties with regard to these two tombs.

JMM1000 is a massive stone-mound tomb measuring 60 m to 70 m per side and presently standing some 11 m in height (Fig. 9). Although it is now largely collapsed, it once contained a stone burial chamber decorated with inscribed bricks that gave it the popular name of “Tomb of a Thousand Autumns.” Excavations in 2003 yielded an inscribed tile fragment that included a date corresponding to 395 or, less likely, 407 (Jilinsheng Wenwu Kaogu Yanjiusuo and Ji’anshi Bowuguan, 2004a:193, 216). On the basis of this tile inscription and supported by the expected chronology based on tomb construction style and roof tile morphology, the tomb is thought to be that of a king named Kogugyang, who died in 391 after a brief reign of seven years (construction of the massive tomb, presumably begun during the king’s lifetime, was not completed until at least four years after his death). The apparent absence of an altar feature was the only factor that ran counter to my hypothesis that such altars are the necessary characteristic identifying kingly tombs. In his 1948 report on his observations in 1938, Fujita Ryosaku noted the existence of some feature to the east of the tomb that he took to be a cluster of attendant tombs, which is how he described what are now known to be altar features associated with other tombs (Fujita, 1948:525). The excavations in 2003, however, uncovered no evidence of such a feature, though the archaeologists would surely have expected to find one (Jilinsheng Wenwu Kaogu Yanjiusuo and Ji’anshi Bowuguan, 2004a:168–216).

Fig. 7. CORONA strip (below) and enlargement of section showing Ji’an (above).

During the course of my analysis of tomb JMM1000 I quickly resolved the problem of the missing altar and was moreover able to account for its later absence. Multiple images of the Maxian region from Korean War overflights provided clear evidence not only for a large altar feature but also for a smaller associated feature of an unknown nature (Fig. 10). Further, a search of early terrestrial images of this tomb clearly shows the northern part of the altar feature, though without the broader context provided by the later aerial imagery its nature would be easy to miss (Fig. 11). Based on measurements of the georeferenced aerial images, the altar feature was located about 40 m to the east of the tomb (approximately where Fujita placed his “attendant tombs”) running parallel to the tomb’s east side. The feature is roughly rectangular, measuring about 30 m by 120 m, and appears to have been constructed of the same stone material as the tomb itself. Approximately 20 m to the south of the altar feature is another raised feature that is roughly square in aspect with rounded corners, measuring about 14 m per side. A straight line running from the northwest corner of the tomb and through the southeast corner would touch the southwestern corner of the smaller feature. Though this may be entirely coincidental, the overall arrangement recalls that of a slightly later tomb numbered JYM0001, located in the northeastern part of the Ji’an plain and popularly called the Tomb of the General (Fig. 12).

Fig. 8. Stone-mounded tomb and its altar feature.

Fig. 9. JMM1000: Tomb of a Thousand Autumns.

Fig. 10. Korea War aerial image showing JMM1000 and associated features. Mission R-21-G-1, frame 16VV, 21 Jan. 1951.

Fig. 11. Early terrestrial image showing part of the altar feature of JMM1000. Photograph courtesy of the National Museum of Korea.

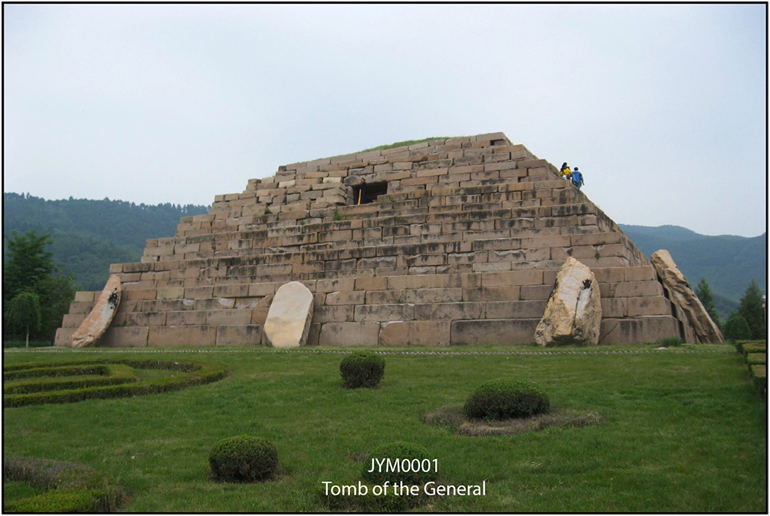

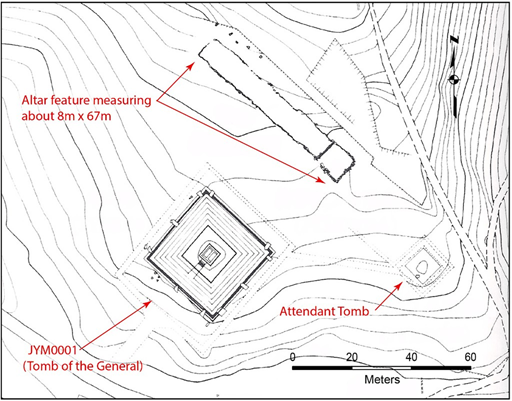

Though JYM0001 is much smaller in scale than JMM1000, it is built of finely worked stone in a pyramidal style, representing the most advanced stage of development of Koguryŏ stone-piled tombs. This tomb is thought to have been built in the early fifth century for King Changsu, who moved the capital to Pyongyang around 427 and was probably buried in that new capital upon his death in 491, leaving the tomb in Ji’an unused. To the northeast of JYM0001 is a ritual altar constructed of worked stone, to the southeast of which is an attendant tomb built in pyramidal style like the primary tomb but in a much smaller scale (Fig. 13). The arrangement of main tomb, altar feature, and attendant tomb seen at JYM0001 very closely resembles that seen at JMM1000. If this is not mere coincidence, the smaller feature at the latter tomb may likewise have been an attendant tomb.

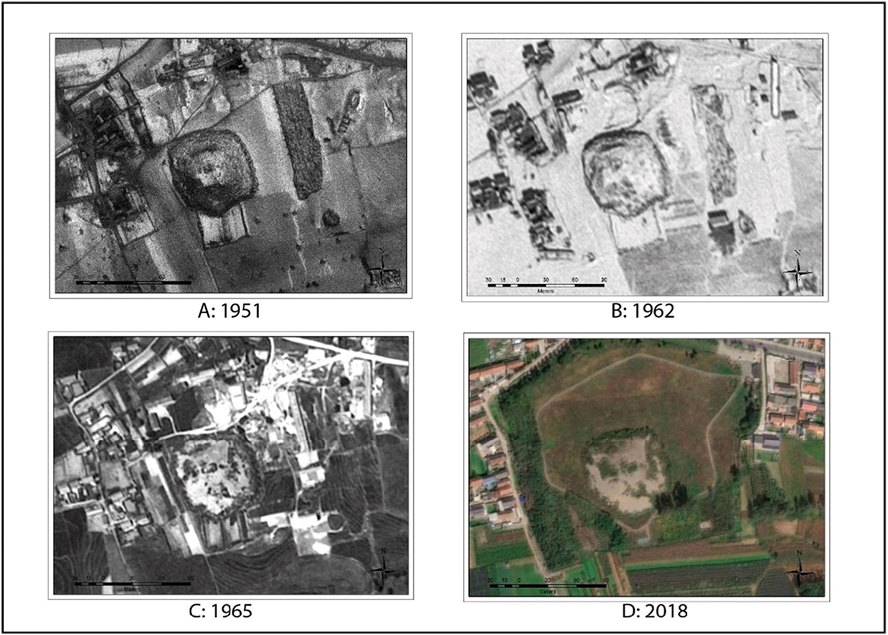

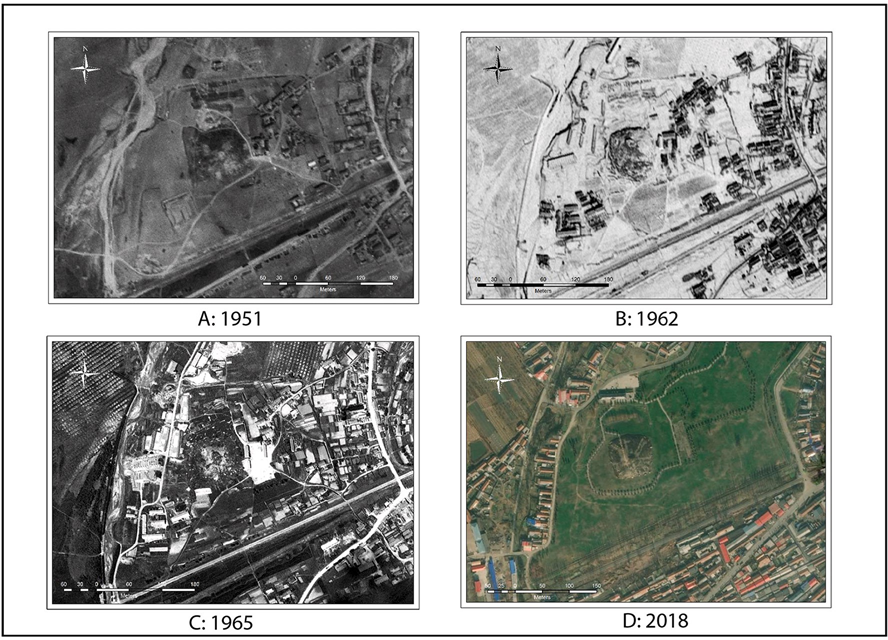

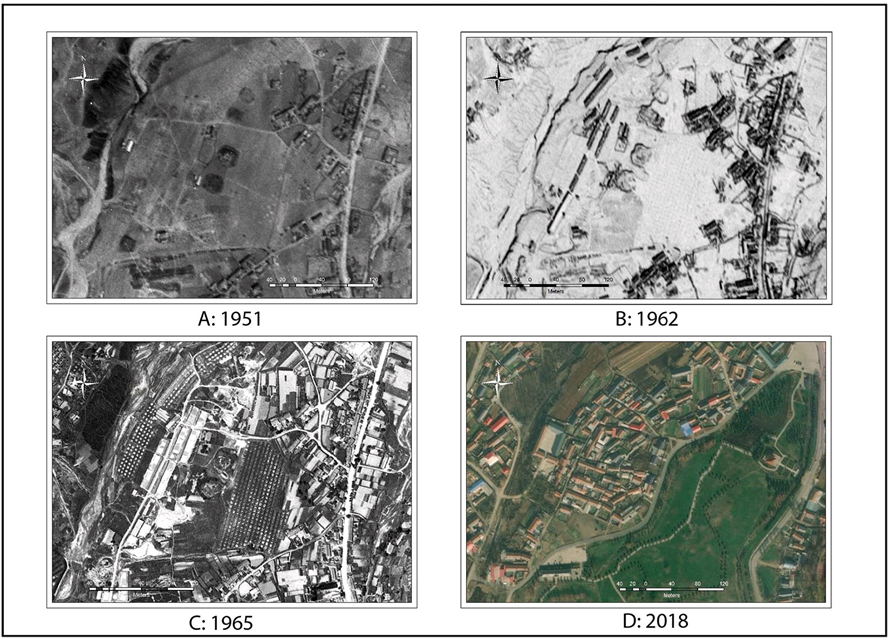

The current absence of the ritual altar for the Tomb of a Thousand Autumns can now be easily explained through a look at later imagery (Fig. 14). Aerial photographs from 1950 and 1951 show a number of small residential buildings just to the north of the altar feature, which appears to be fully intact. High resolution U-2 imagery from 1962 and 1963, however, reveals that the northeastern part of the altar had by then been occupied by additional buildings, while a road had been constructed along the western edge of the altar leading to a large building placed to the south of the altar next to the “attendant tomb” feature. Later U-2 imagery from 1965 shows that within a short time the entire altar feature had been replaced by a number of buildings, including a long structure built along what had been the northern half of the altar. The smaller feature to the south still remained, but the modern structures nearby appear to be expanding in its direction, and the entire area around the main tomb was being developed. Between 1965 and 2000 construction in this area continued, and when the area was cleared for the excavation in 2003, no trace of the altar feature remained for the archaeologists to find—it had been removed to make way for new construction, its stones probably reused for the same purpose. Although the above-ground portion of the smaller feature to the south appears to have been razed, it is possible that future excavations will reveal something of its nature.

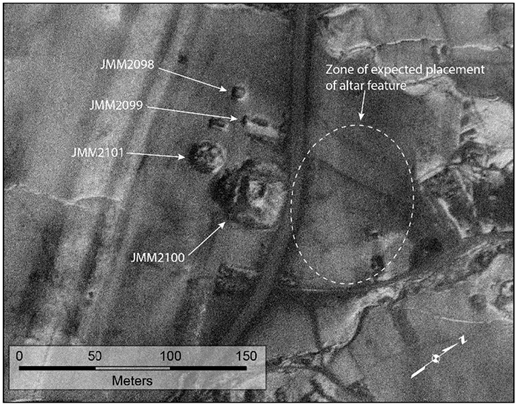

Historical imagery thus illustrates how the advance of urban development has resulted in the complete loss of large archaeological features in Ji’an, and in the same way it can provide useful information about now-lost features that aid in our understanding of surviving remains. In my previous study of Koguryŏ royal tombs, I tentatively included JMM2100, lying about 750 m to the north of the Tomb of a Thousand Autumns, in the list of likely royal tombs. Although smaller in scale than most other tombs with altars, JMM2100 stands out from the typical stone-piled tomb due to its size (about 30 m per side), its structure, and the fact that it stands alone with no other tombs in its vicinity (Fig. 15). Excavations yielded pottery fragments and tile ends allowing us to date it to the mid-fourth century (Jilinsheng Wenwu Kaogu Yanjiusuo and Ji’anshi Bowuguan, 2004a:167), upon which basis I suggested that it might have been the tomb of King Sosurim, who ruled from 371 until his death in 384. There are, however, historical records suggesting that Sosurim may have been buried outside of the Ji’an region. This uncertainty, along with the fact that any ritual altar that may once have existed at this tomb would now lie under either the modern road or the residential buildings nearby, prompted me to consider the identification of JMM2100 as a royal tomb as only tentative. Evidence derived from historical imagery now creates even further doubt that this is the tomb of Sosurim.

Imagery from 1950 and 1951 show this tomb clearly (Fig. 16). Although the road is already present and runs close to the eastern side of the tomb, the area beyond is open field and shows no indication of an altar feature (though it is possible that an existing feature might have been already covered over). More important, however, is the clear presence of a smaller but still substantial tomb lying a very short distance to the northwest of JMM2100. The 1997 register indicates that a stone-piled tomb designated JMM2101 had once existed in this general location but was completely destroyed by the time of that year’s survey. The published register, evidently based on data from the 1966 survey, suggests that the tomb was a commonly found type with a corridor-style entrance, a type of tomb that is usually quite small in scale. (Fig. 17). The imagery shows it to have been only about 7 m to the west of JMM2100, measuring about 20 m per side and similar in construction to its neighbor. Moreover, some 20 m to the north of JMM2101 is a much smaller and possibly damaged tomb (JMM2099), and still another (JMM2098) some 15 m farther to the northwest. Both of these tombs are listed in the 1997 register as destroyed and of the same general type as JMM2101, but the imagery shows that JMM2101 is a much larger tomb than the register would suggest. The compilers of the 1966 and 1997 registers may not have had enough information to describe these lost tombs in more detail, but the present instance illustrates why it is necessary to exercise caution when relying on the published 1997 register for information on lost tombs.

Fig. 12. JYM0001: Tomb of the General.

Fig. 13. Layout of JYM0001 and associated features. After Jilinsheng Wenwu Kaogu Yanjiusuo and Ji’anshi Bowuguan, 2004a:336.

The U-2 imagery from 1962 to 1965 shows that although JMM2101 then still existed next to JMM2100, it was already damaged and there were new buildings abutting it. We may assume that in the following years JMM2101 was completely destroyed, but there was enough of it remaining in 1966 for surveyors to include it in the registry made that year as a stone-piled tomb, the original scale of which was by then indeterminate. Although it is still possible that JMM2100 is a royal tomb, the lack of evidence for an altar feature and the presence of another large tomb in close proximity strongly suggest that this is an elite but non-royal tomb of the mid-fourth century.

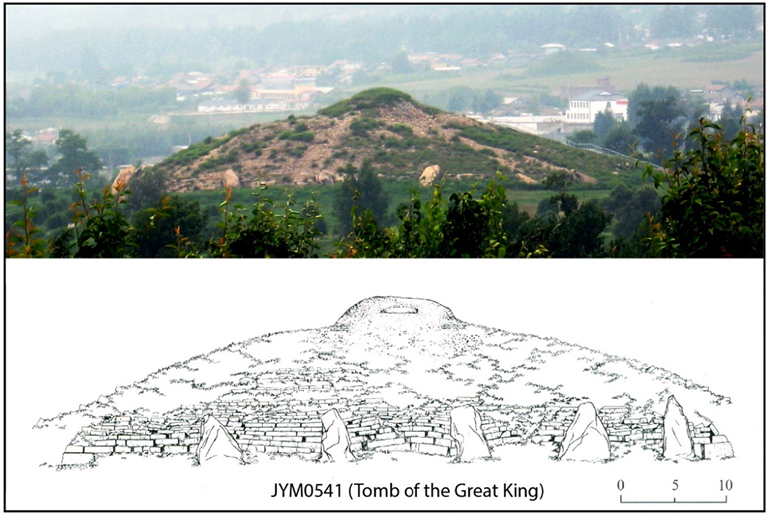

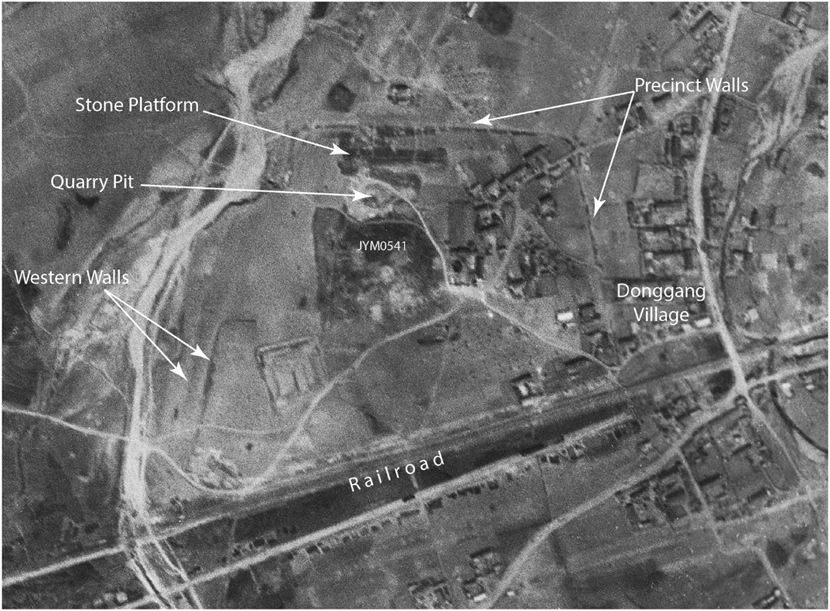

The one tomb in Ji’an that has never been interpreted as anything other than that of a king is JYM0541, popularly called the Tomb of the Great King on the basis of inscribed bricks found among its stones. This tomb sits on a prominent high ground in the eastern half of the Ji’an plain at the village formerly named Donggang, now part of the Taiwang township (Fig. 18). In addition to the inscribed bricks, other characteristics suggestive of a royal tomb are its immense size (more than 60 m per side), a well-constructed burial chamber, evidence of rich burial goods, and clear traces of a wall marking a large tomb precinct with the massive stone-mounded tomb in its center. Excavations conducted in 2003 revealed the presence of a previously unknown pair of adjacent altar features lying some 40 m to the east of the tomb, as well as various additional building structures within the burial precinct (Jilinsheng Wenwu Kaogu Yanjiusuo and Ji’anshi Bowuguan, 2004a:216–335, Fig. 198). The walls of the precinct were known to have existed on the basis of early descriptions of the site, but in 2003 only portions of the eastern and southern walls were identified. The tomb itself dates to the early fifth century and is generally understood as belonging to a king called Kwanggaet’o, who ruled from 391 to 413.

Fig. 14. Aerial images showing destruction of features at JMM1000. A: Mission R-21-G-1, frame 16VV, 21 Jan 1951; B: Mission GRC-128, frame 747 L, 6 Dec. 1962; C: Mission C-425C, frame 784 L, 31 July 1965; ESRI Basemap.

Fig. 15. JMM2100 viewed from southwest corner.

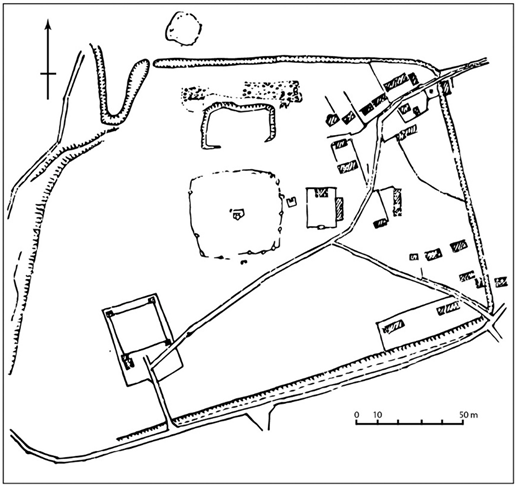

Although decades of surveys and close examination have yielded a great deal of information about this tomb and its associated features, historical imagery adds important additional information that would otherwise now be lost. During the first half of the twentieth century several Japanese scholars produced descriptive reports on this tomb and its vicinity, one of the most detailed being that published by Fujita on the basis of his 1938 survey (Fujita, 1948:513–517). In his report, Fujita included a rough layout sketch of the tomb vicinity, clearly showing the precinct walls, a long rectangular stone platform to the north of the tomb, which strongly suggests an altar feature, and a large stone-piled tomb immediately to the north of the tomb precinct wall (Fig. 19). Interestingly, the rectangular platform described by Fujita, which is no longer extant, is not the altar feature discovered in the 2003 excavation, which lies to the east of the tomb and was already covered with a modern temple complex at the time of Fujita’s survey and therefore does not appear in his report.

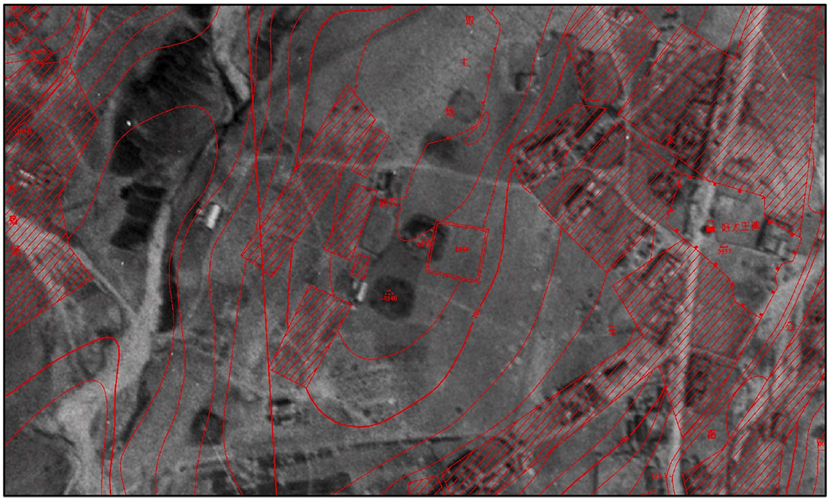

Aerial imagery from the Korean War provides valuable coverage of this site, both vertical and oblique, showing it to have been little changed from the time of Fujita’s visit a dozen years earlier. The precinct walls, constructed of mixed earth and stone, appear clearly and confirm Fujita’s observations, and rectified and georeferenced imagery allows us to plot the location of this now-lost feature with considerable accuracy (Fig. 20). Further, whereas Fujita was unable to discern the western portion of the precinct wall from ground level, the aerial imagery suggests the existence of a pair of parallel walls separated by about 10 m running along the slope to the west, though the exact nature of this feature is not clear. The imagery from the early 1950s shows that the piled-stone platform to the north of the tomb, already damaged at the time of Fujita’s visit, had suffered further damage due to locals removing the stones to use as building materials. A quarry pit between the tomb and this platform appears to have caused further damage to the precinct, while the construction in the late 1930s of the railroad, which runs a few meters to the south of and parallel with the southern precinct wall, may have caused some damage to the tomb complex as well.

Fig. 16. Korea War aerial image showing JMM2100 and vicinity. Mission R-21- G-1, frame 16VV, 21 Jan 1951.

As noted above, the Korea War imagery shows the area around the Tomb of the Great King to be largely unchanged from the time Fujita made his diagram. The U-2 images from 1962 to 1965, however, indicate extensive development in the intervening years (Fig. 21). Numerous buildings had been constructed in the western part of the tomb precinct, modern structures encroaching close upon the tomb itself. The northern and eastern stretches of the precinct walls survived relatively intact as late as 1965, but they had been destroyed by the 1990s (based on my personal observations at that time). Just prior to the clearing of modern structures in preparation for the UNESCO application, the tomb precinct was virtually covered with buildings and other utilities. Although these structures were all removed prior to the excavations in 2003, much of the underlying landscape must have been damaged by the modern encroachments. This should be kept in mind when utilizing the results of the 2003 excavation.

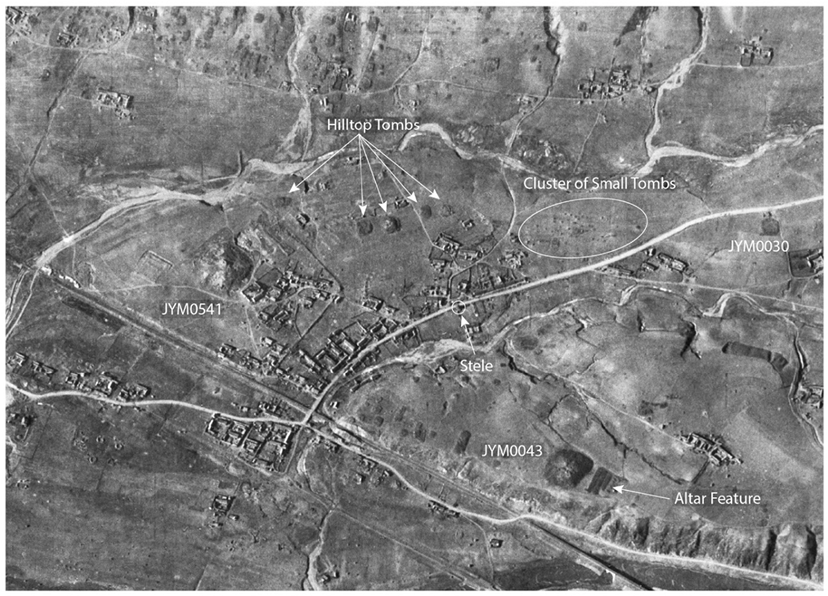

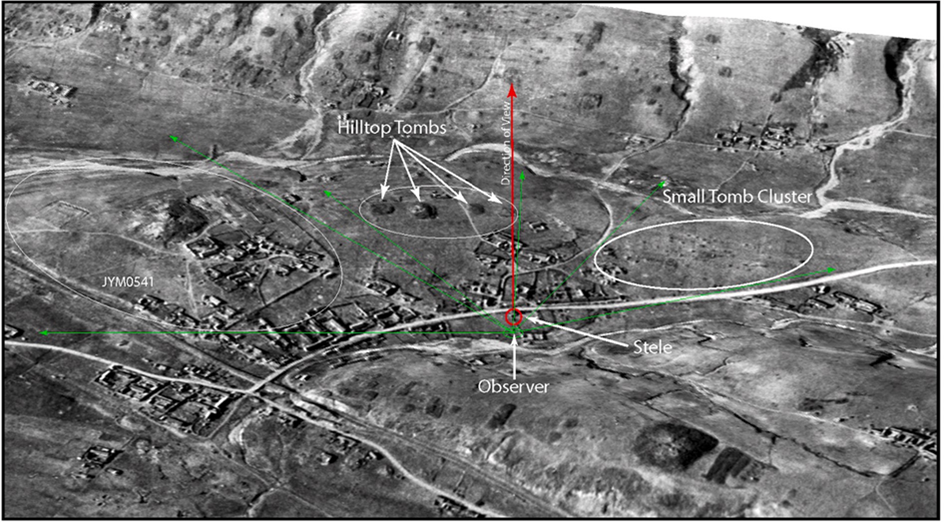

The tomb of the Great King and its walled precinct occupy the southernmost prominence of a low ridge stretching between two major streams, the eastern stream draining the southwestern slopes of Longshan mountain and the western one draining the southeastern slopes of Yushan. To the north of the tomb precinct is a slightly more elevated rise, which was once the site of four large stone-mounded tombs, as will be demonstrated below. Still farther to the north is the lower northern slope of the ridge, which was originally the site of a tight cluster of small stone-piled tombs. Somewhat farther northeastward are the sparse remains of another large tomb designated JYM0030 (also called the Great Tomb at Huangnigang). The mortuary remains in these four zones between the streams are of interest in that they may have been interrelated, as will be discussed below.

Fig. 17. Comparison of images of JMM2100 with 1997 survey map overlay in red. Upper: Mission R-21-G-1; frame 16VV, 21 Jan. 1951; Lower: ESRI basemap, 2018. Overlay from Jilinsheng Wenwu Kaogu Yanjiusuo and Ji’anshi Bowuguan, 2002:268. (For interpretation of the references to colour in this figure legend, the reader is referred to the web version of this article.)

Fig. 18. JYM0541: Tomb of the Great King. Upper: Photograph by author. Lower after Jilinsheng Wenwu Kaogu Yanjiusuo and Ji’anshi Bowuguan, 2004a:224.

Fig. 19. Fujita’s diagram of JYM0541 and vicinity. After Fujita, 1948:514.

The low hill immediately beyond the northern wall of the precinct (or rather what is left of it, as the northwestern part of the hill has been quarried away) is now densely covered with modern residential structures, but it was largely clear of settlement in 1950. In his narrative description of the region to the north of the walled precinct, Fujita notes the existence of five large stone-piled tombs (and two much smaller ones), though his diagram shows the placement of only the one closest to the precinct wall. These five large tombs appear clearly in the Korean War imagery, and the one lying closest to the northern precinct wall appears precisely where it is placed in Fujita’s diagram (Fig. 22). Of these five tombs only one survives today, though in a very poor state of preservation. This tomb is referred to in the 1997 survey as JYM0540, a large-scale tiered stone tomb with sides measuring an estimated 40 m each. The tomb had survived relatively intact until the 1960s, at which time the hill where it was situated became densely settled, with portions of the northern side of the hill extensively quarried by a nearby brick factory. Most of the tomb was presumably disassembled so that its materials could be reused for building homes, and what was left of the tomb underwent excavation in 2003, the report being published in 2009 (Jilinsheng Wenwu Kaogu Yanjiusuo, 2009). Based on its structure and the remains of roof tiles, the tomb was judged to date to the early fifth century, making it roughly contemporary with the Tomb of the Great King, which sits about 250 m to its south.

Fig. 20. Korean War aerial image showing JYM0541 and vicinity. Mission R37-59B, frame 11VV, 8 May 1951.

Fig. 21. Aerial images showing destruction of features around JYM0541. A: Mission R37-59B, frame 11VV, 8 May 1951; B: Mission GRC-128, frame 757 L, 6 Dec. 1962; C: Mission C-425C, frame 799 L, 31 July 1965; ESRI Basemap.

Fig. 22. Korean War aerial image showing JYM0541 and features to its north. Mission R37-59B, frame 11VV, 8 May 1951.

Fig. 23. Hilltop tombs with 1997 survey map overlay in red. Mission R37-59B, frame 11VV, 8 May 1951; overlay from Jilinsheng Wenwu Kaogu Yanjiusuo and Ji’anshi Bowuguan, 2002:192. (For interpretation of the references to colour in this figure legend, the reader is referred to the web version of this article.)

The 1997 survey maps show JYM0540 on the hill north of the Tomb of the Great King, though it is for some reason placed somewhat to the east of its actual location (Fig. 23). Of the other tombs described by Fujita for this area, the 1997 survey notes only two, designated JYM0539 (destroyed) and JYM–0540 (damaged), placed to the west and southwest of JYM0540, respectively (tomb numbers preceded by a dash are used in the 1997 survey publication to indicate tombs that were not included in the 1966 survey). However, there appears to have been some confusion with regard to the identity and placement of these two tombs. The tomb designated JYM0539 was extant during the 1966 survey and underwent more focused survey and limited excavation in Spring of 1968, though the results of this work remain unpublished. The tomb designated JYM-0540 seems to be unrepresented in the 1966 survey and was in 1997 regarded as a newly discovered tomb. In fact, JYM0539 is placed precisely where the tomb now referred to as JYM0540 is located today, while JYM–0540 is placed precisely where another tomb, which I refer to below as 0540a, was once located. It seems likely, therefore, that the tomb today designated JYM0540 is actually the tomb labeled as JYM0539 in 1966 and 1968. The compilers of the 1997 survey data evidently misinterpreted data from the 1966 and 1968 surveys, though it is difficult to resolve this problem without direct reference to the re cords from those earlier surveys.

Several aerial photographs from the early 1950s provide good coverage of the structures located on the hill to the north of the Tomb of the Great King. The five large stone tombs described by Fujita are readily discernible, as they appear as dark patches against the lighter topsoil. They are more or less aligned along the crest of the hill, and for the purposes of this study I have labeled them JYM0540 (retaining the designator from the 1997 survey) and JYM0540a through JYM0540d, based on increasing distance from the surviving tomb. For the sake of brevity, I will hereafter refer to the latter four tombs as Tomb A through Tomb D, as shown in Fig. 22. The photographs indicate that JYM0540 actually measured about 30 m per side, somewhat smaller than the scale estimated in the 1997 survey but close to that resulting from the 2003 excavation. There is clear evidence of its tiered structure, and part of the southwestern third of the tomb appears to have been already removed for the construction of nearby residential buildings. The tomb occupied a prominent position near the summit of the hill.

Tomb A, now completely destroyed, appears as a tomb equal in scale to JYM0540 (about 30 m per side) though placed at a slightly lower elevation, located just to the southwest of the latter tomb, a space of only about 18 m separating the two. There is, however, less evidence for a tiered structure for Tomb A, which appears to have been built lower in profile than its neighbor. Tomb B sits about 38 m to the north of JYM0540 and measured from 20 to 25 m per side, and the photographs show some evidence for a low tiered structure. Immediately to its northeast sits Tomb C, which appears to match the scale and structure of its neighbor, though its central section appears to have been dug out somewhat. A distance of about 14 m separates Tombs B and C, and in fact the relative placement of the four tombs just described suggests that JYM0540 and Tomb A were built as a pair, while Tombs B and C were similarly intended as an associated pair. The latter pair were constructed on the highest summit of the hill.

Tomb D was located some distance from the other four, sitting just 10 m from the northern wall of the precinct for the Tomb of the Great King. The photographs show it precisely where Fujita placed it in his diagram. It sat about 130 m to the southwest of Tomb A, the intervening space showing no evidence of other tombs of a similar scale. It measured about 22 to 25 m per side, and there is some evidence of a low tiered structure. Its placement suggests some association with the royal tomb to its south, but this must remain speculative, as the smaller tomb appears to have been the first of the tombs on this hill to suffer complete destruction.

Although the imagery from the early 1950s shows all of these five tombs as relatively intact, U-2 imagery from 1962 shows that Tomb D had been replaced by a quarry and modern buildings, while the other four tombs survived (Fig. 24). By 1963 Tomb C appears to have succumbed completely to quarrying activity, and in 1965 Tomb B had been replaced by modern buildings and Tomb A, while still clearly evident, was already damaged by encroaching construction. We may assume that by the time of the survey in the next year, Tomb B had suffered further damage to the point where the surveyors described it only as a stone structure, probably of indeterminate scale. By the early 2000s that part of the hill that survived the quarrying activity had been completely covered with modern buildings, leaving only the central part of JYM0540 to be examined by the excavation team in 2003.

On the lower, northeastern slope of the hill, some 140 m distant from Tomb C, is a lower area of the hill that once was the site of a tight cluster of much smaller tombs distributed in a zone stretching about 200 m from the southwest to northeast and about 70 m from northwest to southeast (Fig. 25). The 1997 survey publication records some 33 small tombs in this zone, three being earth-mounded stone-chamber types and the remainder stone-piled corridor-entry types. All are listed as destroyed in 1997, and the data for them were apparently drawn from the 1966 survey as well as two focused (but unpublished) surveys in 1968. Korean War imagery confirms the existence and placement of these tombs (along with what appear to be a few other tombs of similar style that may not have survived to 1966), but their small scale and the insufficient resolution of the imagery make it difficult to determine anything about their specific size, construction, or chronology. U-2 imagery reveals that the area occupied by the small tomb mounds has been developed as fields for planting and, on the southern edge of the zone, for residential structures, suggesting that many tombs might have been damaged or destroyed prior to the 1966 survey. Today the entire area has been covered with modern buildings or otherwise utilized for production.

Fig. 24. Aerial images showing destruction of hilltop tombs north of JYM0541. A: Mission R37-59B, frame 11VV, 8 May 1951; B: Mission GRC-128, frame 757 L, 6 Dec. 1962; C: Mission C–425C, frame 799 L, 31 July 1965; ESRI Basemap.

Fig. 25. Korea War oblique image showing Donggang and area around JYM0541. Mission R-25-EE-1, frame 27LS, 25 Nov. 1950.

Fig. 26. King Kwanggaet’o stele. Photograph courtesy of the National Museum of Korea.

The hill occupying the space between the two streams thus appears to have been reserved for mortuary purposes during the late fourth and early fifth centuries, with the large stone-piled tombs occupying the highest central elevation, flanked by the royal tomb complex to the south and the cluster of small tomb mounds to the northeast. Still farther to the northwest another hill rises, and on its southern slope, about 200 m from the cluster of small mounds, sits the only other tomb known to have existed in the region between the two streams. This is the large stone-mounded JYM0030, otherwise called the Great Tomb at Huangnigang. This tomb, measuring roughly 30 m per side, appears to have been much damaged by the time of the Korea War, though its outline is clear and relatively sharp in the imagery from the early 1950s. The tomb suffered further damage in the second half of the twentieth century until it underwent close survey and limited excavation in Autumn of 2003, by which time little other than its perimeter outline remained (Jilinsheng Wenwu Kaogu Yanjiusuo and Ji’anshi Bowuguan, 2009). Although its scale and evident chronology (fifth century) suggest that it may have some relationship with the mortuary features in the other three zones considered here, lack of more specific information and the fact that it occupies an adjacent hill prompt me to set it aside from the discussion below, which will focus primarily on the large tombs on the hilltop.

As a result of the destruction caused by modern development and the lack of detailed surveys predating 1966, data concerning the spatial placement and scale of these tombs to the north of the Tomb of the Great King (and in some cases even the fact of their existence) had been almost completely lost. As this study reveals, however, the georeferenced aerial imagery dating from the Korean War allows us to recover much of this information along with important associated topographical data. Although Donggang was the site of a small village in 1950, the modern settlement had not encroached on the ancient remains to the point where, like today, the landscape itself had been significantly altered by human activity. In the area surrounding the village there are two royal tombs, including the Tomb of the Great King (JYM0541) and, on a hilltop across the stream to the east, another massive tomb designated JYM0043, popularly called the River-Viewing Tomb, as it sits on a high bluff overlooking the Yalu valley (see Fig. 25). The latter is an early royal burial probably dating to the mid-third century. The 2003 excavations in Ji’an revealed the existence of a large altar feature to the east of the River-Viewing Tomb, which is also clearly visible in the aerial imagery of the early 1950s. There are no other tombs in its immediate vicinity, suggesting the existence of a recognized (but unwalled) tomb precinct, but there are a number of much smaller tombs along the bluff and on the nearby hills surrounding the royal tomb to a distance of about 350 m, the largest of which barely exceed 20 m per side.

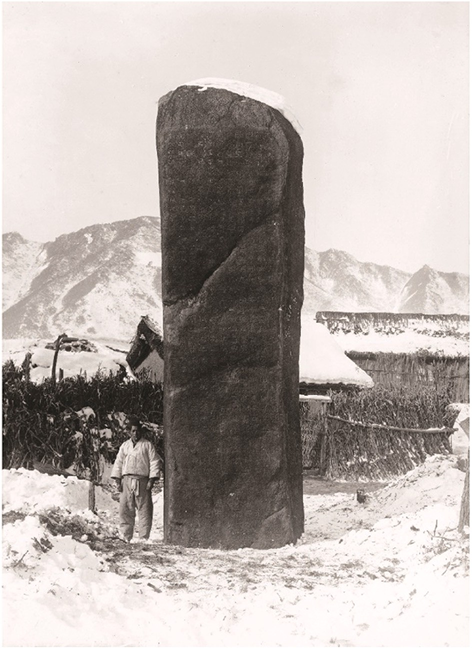

By contrast, the five tombs on the hill to the north of the Tomb of the Great King vary from 22 to 32 m per side, and they are much fewer in number. Their scale and placement suggest a close relationship with the nearby royal burial, possibly indicating members of the king’s family or his elite ministers. Another indication of their possible importance in Koguryŏ mortuary practice is the fact that about 180 m to their east sits the King Kwanggaet’o stele, erected in 414 a year after the death of Kwanggaet’o, who is thought to be the occupant of the Tomb of the Great King (Fig. 26). Scholars in East Asia have long been troubled by the fact that the placement of this stele reveals no clear alignment with any of the royal tombs in the area, as would be expected in a Chinese context. Evidence, however, suggests that Koguryŏ did not follow Sinitic modes of burial practice, and the placement of the stele may not reflect orientation toward any particular tomb. The large granite stele stands 6.4 m tall and is inscribed on all four sides in Chinese script, the text extolling the merits of King Kwanggaet’o. The long text, nearly 1800 characters in length, begins on the southeastern face and proceeds top to bottom and right to left around the entire circumference of the stone.

A reader facing the front side of the stele in Koguryŏ times could have seen the Tomb of the Great King to the left (i.e., the southwest) at a distance of about 350 m (Fig. 27). The four large tombs on the hill crest would have been prominently visible almost directly behind and slightly to the left of the stele, provided, of course, that the view was not obstructed by trees or buildings. The fact that these tombs, placed so close to the royal tomb, would have been prominently visible from the site of the stele suggests some significance in their placement that may relate to Koguryŏ funerary practice or ritual. The same viewer would have been able to see the cluster of smaller tombs to the right of the stele at a distance of about 180 m, provided, again, that there were no natural or manmade obstructions. Assuming that these small tombs are contemporary with the nearby royal burial (early fifth century), they may represent the interments of non-elite members of the king’s extended household. Another possibility is that these are the tombs of some of the so-called tomb guardian households, which are described in the stele inscription as having been tasked with the maintenance of the mausoleum grounds. Although this is speculation, it is not unlikely that the guardian households would have lived in the vicinity of the mausoleum and might also have been buried nearby. In any case, the tight placement of these smaller tombs on the northeastern slope of the hill suggests the possibility of some significant connection with the royal tomb complex. That the tombs discussed above would have been conspicuously visible from the location of the King Kwanggaet’o stele is also suggestive of a deliberate placement, possibly reflecting an elite mortuary practice associated with Koguryŏ’s high middle period.

Although we do not know the chronology of most of these hilltop tombs, JYM0540 was dated to the early fifth century, making it roughly contemporary with the royal burial to the south. Knowledge of the original placement of the other tombs discussed here might afford archaeologists an opportunity to explore those areas in the future in an effort to seek any traces that might survive beneath the modern buildings (though Tomb C and possibly Tomb B may have been completely destroyed by quarrying activity). Tomb D would not have been prominently visible from the stele, and its placement so close to the precinct wall of the royal tomb may indicate that it predated the creation of the precinct, suggesting the possibility that still other tombs may have been removed for the construction of the precinct in the late-fourth or early-fifth century. Unfortunately, historical imagery does not provide answers to such questions, but it suggests to archaeologists a broader range of interpretive possibilities when considering Koguryŏ mortuary practice.

Conclusions

The research results presented above illustrate how the use of historical imagery in a GIS environment can result in the recovery of archaeological information that would previously have been considered as irretrievably lost. The present study focuses only on mortuary features, but the same methods may be applied to the study of other above-ground archaeological features, such as walled sites. Such studies would be of potential use to researchers who have recently begun to apply GIS and related landscape modeling tools to close analyses of Koguryŏ for tresses in northeastern China (Liu, 2020; Xu, 2020). The methods described above have revealed the existence and placement of important mortuary features in Ji’an that were either previously unknown or had been lost before they could be subjected to detailed survey. As shown above, the existence or absence of altar features in historical imagery allow us to gauge the likelihood that certain tombs represent royal interments, and the reconstruction of the broader landscape surrounding certain royal tomb precincts enables us for the first time to interpret how the relative placement of tombs and stelae suggest a deliberate arrangement that would be otherwise invisible to us. Such finds represent new information that deepen our understanding of elite mortuary practice and the utilization of the landscape in the Koguryŏ capital of the fourth to fifth centuries.

The usefulness of GIS and aerial imagery as an aid to archaeological research has been well attested in recent years, and it has been increasingly utilized in the study of northeast Asian archaeology. However, the relative difficulty of identifying and accessing the relevant imagery for certain regions in East Asia, including the Yalu River region treated in this study, and the fact that most of these resources are located in the United States, where there are relatively few archaeologists who research East Asia, has resulted in some of those valuable resources having been underutilized. Having developed a set of finding aids that diminishes the difficulties in imagery identification and acquisition, I have made much progress in the study of lost archaeological features in northeastern China and northern Korea. The present study represents a sample of finds from the ancient Koguryŏ capital of Ji’an on the north bank of the Yalu River in China.

The research results described above illustrate the value of historical imagery in identifying and mapping above-ground archaeological features, tomb mounds in particular, that have succumbed to urban development since the mid-twentieth century. Although such research demands a considerable investment of time and energy, the rewards yielded are similarly great. In the present study we see a glimpse of how the mapping of tomb mounds and their associated features, many of which have been lost without adequate documentation, allows us to gain a richer understanding of the mortuary practices observed by Koguryŏ elites and of how certain significant areas of the capital city were allocated for mortuary purposes. The results of this study also illustrate that researchers must use appropriate caution when utilizing archaeological reports and the comprehensive tomb registers produced in Ji’an. The uneven documentation of archaeological remains in Ji’an over the past century and more makes it difficult for researchers today to appreciate how urban development, especially since the 1960s, has erased much of the archaeological landscape of this area. Very often ignorance of the fact that such an erasure has occurred can result in erroneous interpretation of surviving remains.

Fig. 27. Features in Donggang showing observation perspective from King Kwanggaet’o stele. Image from Fig. 25 rubber-sheeted over SRTM DEM using ESRI’s ArcView.

This research has shed new light on some limitations and advantages in the basic methodological approach to the study of archaeological remains in Ji’an and elsewhere. The most important of the limitations involves the published results of the 1997 survey of tombs. Although this is an immensely valuable work for the study of Koguryŏ archaeology, it cannot always be relied upon for accurate data, particularly where now-destroyed tombs are concerned.6 A careful analysis of the Ji’an region through historical imagery should facilitate an improved and more accurate catalogue of the pre-development tomb inventory of Ji’an. However, while the use of such imagery is useful for identifying lost features, mapping them with precision, and estimating their measurements, the fact that most features of this type can never be analyzed firsthand indicates a certain limitation on the extent to which we may confidently make interpretations. This limiting factor may be ameliorated somewhat by a careful choice of research questions and by making use of comparative analysis using surviving features.

The advantages of utilizing historical imagery are numerous, and here I will mention only a few of them. The most basic advantage is that such imagery provides a unique record of now-lost archaeological remains, and without such imagery there is no evident method of identifying or mapping such lost features. Although high resolution satellite data from recent years offers unparalleled multispectral optical data of the region, in the case of Ji’an we are limited to viewing only the heavily urbanized landscape of recent years, and even the process of identifying individual tomb mounds through such imagery can be quite daunting as they are often drowned out by the encroaching development. By contrast, in historical imagery, especially that from the Korea War, tomb mounds stand out in stark contrast from their surroundings, making the process of mapping individual tombs much easier. Further, there is significant advantage in comparing as many different images as possible of a single area, as each image reveals certain details that others lack as variations of season and angle of illumination provide clear distinctions in surface detail. Careful processing of the imagery, through contrast stretching for example, allows the viewer to draw out selected types of information, a process that facilitates the easy distinction between stone-mounded and earth-mounded tombs. Moreover, as illustrated above, comparison of imagery of a single region over time allows us to map the process of development, which often helps to explain why certain archaeological features have vanished.

Beyond the fact that historical imagery allows access to now-lost archaeological remains, it further provides valuable information on the basic landscape of the region prior to significant urban development. Besides the construction of embankments to protect the town from flooding and erosion, Ji’an has seen extensive reworking of the landscape through quarrying activity, damming of rivers, and the covering or rerouting of natural drainage channels. Each of these activities results in the erasure of elements of the premodern landscape, which can impact our understanding of how ancient populations utilized space.

One of the longer-term goals of my work with historical imagery is to reconstruct the pre-development landscape of Ji’an. Since most of the aerial imagery utilized in this research was designed to produce over lapping photographs, or stereopairs, for the use of photogrammetric measurements, they can also now be used to generate a digital elevation model (DEM), which allows us to create a three-dimensional model of the topography depicted in the imagery. A further advantage of this approach is that the terrain model thus produced represents the pre- development landscape, an advantage not provided by existing satellite-generated DEMs, such as SRTM or ASTER, which represent only the landscape of the 2000s. A further limitation of most existing freely available DEMs is that their best resolution is often insufficient to account for subtle variations in surface contours, which a finer resolution of the area through historical imagery can provide. By draping georeferenced aerial imagery over a DEM, we produce a three-dimensional digital model of the region through which we may move freely, which opens a window for the macro-analysis of the pre-development landscape. The digital integration of archaeological data from imagery, surveys, and excavations, into a three-dimensional surface model pro vides a rich analytical potential for close study of the pre-development archaeology and landscape of the Ji’an region. As such an approach has to date been wholly unexplored in the context of this region, we may expect the process to result in considerable yield and value.

References

Appleman, Roy E., 1961. South to the Naktong, North to the Yalu (June–November 1950). Office of the Chief of Military History, Department of the Army, Washington DC.

Azuma, Ushio, 2016. Historical changes in Koguryŏ tombs. In: Byington, Mark E. (Ed.), The History and Archaeology of the Koguryŏ Kingdom. Korea Institute, Harvard University, Cambridge, MA, pp. 319–372.

Byington, Mark E., 2019. Identification and chronology of some Koguryŏ royal tombs. Asian Perspect. 58-1, 7–27.

Casana, Jesse, Cothren, Jackson, 2008. Stereo analysis, DEM extraction and orthorectification of CORONA satellite imagery: archaeological applications from the near east. Antiquity 82 (September), 732–749.

Casana, Jesse, Cothren, Jackson, 2013. The CORONA Atlas Project: Orthorectification of CORONA satellite imagery and regional-scale archaeological exploration in the near east. In: Comer, Douglas C., Harrower, Michael J. (Eds.), Mapping Archaeological Landscapes from Space. Springer, New York, pp. 33–43.

Comer, Douglas C., Harrower, Michael J. (Eds.), 2013. Mapping Archaeological Landscapes from Space. Springer Briefs in Archaeology. Springer, New York. Conolly, James, Lake, Mark, 2006. Geographical Information Systems in Archaeology.

Cambridge Manuals in Archaeology. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, UK

and New York.

Day, Dwayne A., Logsdon, John M., Latell, Brian (Eds.), 1998. Eye in the Sky: The Story of the CORONA Spy Satellites. Smithsonian Institution Press, Washington and London.

Fujita, Ryosaku, 1948. Ts uko fukin no kofun to Kokuri bosei [Tombs in Tonggou and the Koguryŏ mortuary system]. In: Fujita, Ryosaku (Ed.), Chosen kokogaku kenkyu [Studies of Korean Archaeology]. Takagiri Shoin, Kyoto, pp. 497–540 (In Japanese).

Hammer, Emily, Ur, Jason, 2019. Near eastern landscapes and declassified U2 aerial imagery. In: Advances in Archaeological Practice. Society for American Archaeology, pp. 1–20. https://doi.org/10.1017/aap.2018.38.

Hanson, William S., Oltean, Ioana A. (Eds.), 2013. Archaeology from Historical Aerial and Satellite Archives. Springer, New York.

Hao, Yuanlin, Moriya, Kazuki, 2017. CORONA yingxiang zai chengshi kaogu zhong de yingyong [The application of CORONA satellite imagery in urban archaeology]. Bianjiang kaogu yanjiu 22, 313–323 (In Chinese).

Hŏ, Ǔihaeng, 2021. Silla wanggyŏng nae palch’ŏn kwa chubyŏn ˘ ui kojihyŏng hwan’gyŏng [The paleotopographical environment surrounding Pal Stream within the Silla royal capital]. Silla munhwa 58, 135–155. https://doi.org/10.37280/ JRISC.2021.06.58.135 (In Korean).

Hŏ, Ǔihaeng, Yang, Chŏngsŏk, 2021. Taebong Ch’ŏrwŏn tosŏng ˘ ui kojihyŏng kwa kujo punsŏk yŏn’gu [A study on the paleotopographic and structural analysis of the Taebong walled site in Ch’ŏrwŏn]. Munhwajae 54 (2), 38–55. https://doi.org/ 10.22755/kjchs.2021.54.2.38 (In Korean).

Hu, Ningku, Li, Xin, Luo, Lei, Zhang, Liwei, 2017. Ancient irrigation canals mapped from Corona imageries and their implications in Juyan Oasis along the silk road. Sustainability 9. https://doi.org/10.3390/su9071283.

Ji’anxian Difangzhi Biansuan Weiyuanhui, 1987. Ji’anxian zhi [Gazetteer of Ji’an County]. Ji’anxian Difanghi Biansuan Weiyuanhui (In Chinese).

Jilinsheng Wenwu Kaogu Yanjiusuo, 2009. Ji’an Yushan 540 hao mu qingli baogao [Report of the excavation of tomb 540 at Yushan in Ji’an]. In: Jilinsheng Wenwu Kaogu Yanjiusuo (Ed.), Jilin Ji’an Gaogouli muzang baogaoji [Reports on Koguryŏ Tombs in Ji’an]. Kexue Chubanshe, Beijing, pp. 306–320 (In Chinese).

Jilinsheng Wenwu Kaogu Yanjiusuo, Ji’anshi Bowuguan, 2002. Donggou gumuqun: 1997 nian diaocha cehui baogao [The Donggou Cemetery: Report on the 1997 Investigation and Survey]. Kexue Chubanshe, Beijing (In Chinese).

Jilinsheng Wenwu Kaogu Yanjiusuo, Ji’anshi Bowuguan, 2004a. Ji’an Gaogouli wangling [Koguryŏ Royal Tombs in Ji’an]. Wenwu Chubanshe, Beijing (In Chinese).

Jilinsheng Wenwu Kaogu Yanjiusuo, Ji’anshi Bowuguan, 2004b. Guoneicheng – 2000–2003 nian Ji’an Guoneicheng yu Minzhu yizhi shijue baogao [Guoneicheng: Report on the 2000–2003 Test excavations at the Guoneicheng and Minzhu Sites in Ji’an]. Wenwu Chubanshe, Beijing (In Chinese).

Jilinsheng Wenwu Kaogu Yanjiusuo, Ji’anshi Bowuguan, 2004c. Wandu shancheng: 2001–2003 nian Ji’an Wandu shancheng diaocha shijue baogao [Wandu Mountain Fortress: Report of the 2001–2003 Survey and Test Excavation of Wandu Mountain Fortress in Ji’an]. Wenwu Chubanshe, Beijing (In Chinese).

Jilinsheng Wenwu Kaogu Yanjiusuo, Ji’anshi Bowuguan, 2009. Huangnigang damu diaocha baogao [Report on the Survey of the Great Tomb at Huangnigang]. In: Jilinsheng Wenwu Kaogu Yanjiusuo (Ed.), Jilin Ji’an Gaogouli muzang baogaoji [Reports on Koguryŏ Tombs in Ji’an], ed., Jilinsheng Wenwu Kaogu Yanjiusuo. Kexue Chubanshe, Beijing, pp. 300–305 (In Chinese).

Jilinsheng Wenwu Kaogu Yanjiusuo, Ji’anshi Wenwu Baoguansuo, 1993. Ji’an Donggou gumuqun Yushan muqu Ji-Xi gonglu muzang fajue [Excavations of tombs along the Ji’an–Xilinhot road in the Yushan cluster of Ji’an’s Donggou Cemetery]. In: Geng, Tiehua, Sun, Renjie (Eds.), Gaogouli yanjiu wenji [Collected Studies on Koguryŏ]. Yanbian Daxue Chubanshe, Yanji, pp. 21–79 (In Chinese).

Jilinsheng Wenwuzhi Bianweihui, 1984. Ji’anxian wenwuzhi [Cultural Gazetteer for Ji’an County]. Jilinsheng Wenwuzhi Bianweihui, Changchun (In Chinese).

Lasaponara, Rosa, Yang, Ruixia, Chen, Fulong, Li, Xin, Masini, Nicola, 2018. Corona satellite pictures for archaeological studies: a review and application to the lost Forbidden City of the Han-Wei Dynasties. Surv. Geophys. 39 (6), 1303–1322.

Li, Min, 2013. Archaeological landscapes of China and the application of Corona images. In: Comer, Douglas C., Harrower, Michael J. (Eds.), Mapping Archaeological Landscapes from Space. Springer, New York, pp. 45–54.

Liu, Zhao, 2020. Zhongguo jingnei Gaogouli shancheng xianzhi yanjiu [Research on the Placement of Koguryŏ Mountain Fortresses in China]. Masters thesis. Shenyang Jianzhu University, Shenyang, China (In Chinese).

Sawada, Hidemi, 2002. Kuchu shashin ni yoru Tamateyama kofun no fukugen [Restoration of the Tamateyama tumulus through aerial photography]. In: Kashiwarashi Kyoiku Iinkai (Ed.), Tamateyama kofun’gun no kenkyu II: Funkyu hen [Studies on the Tamateyama tumulus II: Tomb mound volume]. Kashiwarashi Kyoiku Iinkai, Kashiwarashi, Okayama, pp. 106–120 (In Japanese).

Sawada, Hidemi, 2011. Kuchu shashin o mochiita inmetsu kofun no fukugenteki kenkyu kaken hokoku [Report on the restoration of destroyed tomb mounds using aerial photography]. In: 2007-nendo–2010-nendo Kagaku kenkyuhi hojokin kiban kenkyu (B) kenkyu seika hokokusho [Report of Grants-in-Aid for Scientific Research, submitted to the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science in 2007 to 2010]. Kurashiki Sakuyo Daigaku, Kurashiki-shi, Okayama (In Japanese).

Shandongsheng Wenwu Kaogu Yanjiusuo, 2000. Zhongguo Linzi wenwu kaogu yaoganying xiangtu ji [The Archaeological Aerial Photo-Atlas of Linzi, China]. Shandongsheng Ditu Chubanshe, Jinan-shi (In Chinese).

Sohn, Hong-Gyoo, Kim, Gi-Hong, Yom, Jae-Hong, 2004. Mathematical modelling of historical reconnaissance CORONA KH-4B imagery. Photogramm. Rec. 19 (105), 51–66.

Watanabe, Nobuya, Nakamura, Shinichi, Liu, Bin, Wang, Ningyuan, 2017. Utilization of structure from motion for processing CORONA satellite images: application to mapping and interpretation of archaeological features in Liangzhu Culture, China. Archaeol. Res. Asia 11 (Sept.), 38–50. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ara.2017.06.001.

Wei, Cuncheng, 1994. Gaogouli kaogu [Koguryŏ Archaeology]. Jilin Daxue Chubanshe, Changchun (In Chinese).

Xu, Chao, 2020. Zhongguo jingnei Gaogouli shancheng kongjian xingtai yanjiu [Research on the Spatial Morphology of Koguryŏ Mountain Fortresses in China]. Masters thesis. Shenyang Jianzhu University, Shenyang, China (In Chinese).

Yanaka, Toshio, 2018. Oido kofun no funkyu ni tsuite [Concerning the mound of the Oido tumulus]. In: Ken’ichi Sasaki (Ed.), Kasumi-ga-uru no zenpokoenfun–Kofun bunka niokeru chuo to shuen [The Kasumi-ga-uru keyhole tumulus: Center and Periphery in Kofun Culture]. Meiji Daigaku Kokogaku Kenkyushitsu, Tokyo, pp. 179–185 (In Japanese).

Zhang, Li, Wu, Jianping, 2007. Zhejiang Yuhang pingyao Liangzhu gucheng jiegou de yaogan kaogu [Remote sensing archaeology of the structures of the walled sites at Pingyao and Liangzhu in Yuhang, Zhejiang]. Wenwu 2, 74–80 (In Chinese).

Notes

1 The town ’s population is listed as 48,317 in 1906, 129,404 in 1930, 121,826 in 1944, and 208,104 in 1982, though this growth may also represent changes in administrative boundaries (Ji ’anxian Difangzhi Biansuan Weiyuan hui, 1987:48). China ’s Baidu website for Ji ’an lists the population in 2013 as 218,623 (https://baike.baidu.com/item/%E9%9B%86%E5%AE%89, accessed January 25, 2019).

2 This figure differs from the 11,300 tombs totaled in the associated table appearing in the published results of the later 1997 survey (Jilinsheng Wenwu Kaogu Yanjiusuo and Ji ’anshi Bowuguan, 2002:9). To date I have not been able to access the 1966 survey data directly to determine the reason for this discrepancy.