Crime Present and Crime Past

Patrick Anderson

I.

Crime Present and Crime Past

Wherein a middlebrow ventures onto the thriller beat, Edgar Allan Poe inflicts bloody murder on the Rue Morgue, Arthur Conan Doyle sends forth the original dynamic duo, Agatha Christie takes on Shakespeare and the Bible, hard-drinking Americans invent the hardboiled detective novel, and postwar Americans graduate from the pulps to semi-respectability.

1. A New Beat

In 2000, Marie Arana, the editor of the Washington Post Book World, put me on the thriller beat. I had for years reviewed both fiction and nonfiction for Book World, but now Marie wanted me to focus on the crime-related novels that have come to dominate the bestseller lists. Soon I began reviewing a new book each Monday in the Post’s free-wheeling Style section.

Over the years, reading purely for pleasure, I’d become a fan of such writers as John D. MacDonald, Lawrence Sanders, Elmore Leonard, Ross Thomas, Ed McBain, James Lee Burke, Thomas Harris, and Michael Connelly. Now, reading thrillers on a regular basis, I learned how much more talent was out there. I discovered people like Dennis Lehane, Ian Rankin, Donna Leon, Robert Littell, George Pelecanos, John Lescroart, and Alan Furst. I reviewed bestsellers by John Grisham, Tom Clancy, Sue Grafton, John Sandford, James Patterson, and Patricia Cornwell; some I admired, some I deplored, but their success says something about our popular culture. I’ve also had the pleasure of telling our readers about new talent like Karin Slaughter, David Corbett, Robert Reuland, and Charlie Huston.

The more I read, the more I was struck by the transformation in America’s reading habits. I grew up with the blockbuster novels of the 1950s and 1960s, written by people like James Michener, Harold Robbins, John O’Hara, Jacqueline Susann, Herman Wouk, and Irving Stone. They explored sex, money, movie stars, war, religion, and exotic foreign lands but rarely concerned themselves with crime. In those days, crime novels were trapped in the genre ghetto, often published as paperback originals, and rarely won a mass audience.

Today, those blockbuster novelists have been replaced on the bestseller lists by the crime-related fiction we loosely call thrillers, which includes hard-core noir, in the Hammett-Chandler private-eye tradition, as well a bigger, broader universe of books that includes spy thrillers, legal thrillers, political thrillers, military thrillers, medical thrillers, and even literary thrillers. I have a copy of the December 25, 1966, Book World – incredibly enough, I had a review in it. Starting at the top, the ten authors on the fiction bestseller list are Robert Crichton, Allen Drury, Jacqueline Susann, Rebecca West, Mary Renault, Edwin O’Connor, James Clavell, Bernard Malamud, Harold Robbins, and Harry Mark Petrakis. Two political novelists, two or three literary writers, two grandmasters of sex and schlock – but no crime fiction.

Compare that with a Book World list in February of 2006. By my count, nine of the ten books listed were thrillers, including Stephen King’s Cell, Dan Brown’s The Da Vinci Code, Sue Grafton’s S is for Silence, and John Lescroart’s The Hunt Club. Another Sunday that month, the New York Times Book Review had fifteen thrillers among its sixteen hardback bestsellers, including those on the Post’s list plus Greg Iles’ Turning Angel, and various lesser works. The transformation between the lists in 1966 and 2006 could not be more dramatic. To oversimplify a bit, John Grisham is the new James Michener and The Da Vinci Code is our Gone With the Wind.

In this book, I’ll look back to the origins of modern crime fiction – to writers like Edgar Allan Poe, Arthur Conan Doyle, and Agatha Christie – to examine how the modern thriller has evolved. The triumph of the thriller, I call this transformation. We will grapple with questions of definition. Just what is a thriller? How is it different from a mystery or a crime novel? The terminology is far from precise but let me suggest a few guidelines. Christie and her imitators wrote mysteries that stressed intellectual solutions to crimes. Her tradition continues in so-called cozies that appeal to readers who want no violence and in more ingenious novels by writers like the American Martha Grimes.

In this country, around 1930, Dashiell Hammett invented the American crime novel, also known as the detective or private-eye novel, and Raymond Chandler built on Hammett’s work. Their hard-boiled tradition prevailed for several decades, but by the 1970s the crime novel began to mutate into something that was bigger, darker, more imaginative, and more violent – the modern thriller. Certain novels have been milestones in expanding the boundaries of the thriller – among them Lawrence Sander’s The First Deadly Sin, Frederick Forsyth’s The Day of the Jackal, Scott Turow’s Presumed Innocent, Tom Clancy’s The Hunt for Red October, John Grisham’s The Firm, Thomas Harris’s The Silence of the Lambs, and Dennis Lehane’s Mystic River.

John Updike said this while reviewing Robert Littell’s surreal spy novel Legends in the New Yorker in 2005: “The slippery difference between a thriller and a non-thriller would hardly be worth groping for did not the thriller-writers themselves seem to be restive – chafing to escape, yearning for a less restrictive contract with the reader. They write longer than they used to, with more flourishes.” Updike notes that Agatha Christie’s ambitions never extended past the lean, efficient mysteries she wrote, but “Littell and le Carre and the estimable P.D. James give signs of wanting to be ‘real’ novelists, free to follow character where it takes them and to display their knowledge of the world without the obligation to provide a thrill in every chapter.”

The estimable Updike might have gone further and added a number of other thriller-writers to his list of restive souls, many of whom have gone beyond wanting to be real writers to doing it. Novels like Bangkok 8, Hard Revolution, Tropic of Night, Done for a Dime, Presumed Innocent, Legends, Red Dragon, Lost Light, and The Way the Crow Flies are simply some of the best fiction being written today.

I had some misgivings when Marie put me on the thriller beat. I was an English major in the uptight 1950s, when the high modernists – T.S. Eliot, James Joyce, William Faulkner – were force-fed to undergraduates, and for years I felt a tremor of guilt when I stooped to popular fiction and certainly to thrillers. A lot of people of my generation felt that way. When my political thriller The President’s Mistress was published in 1976, the Washington Post’s reviewer declared that she locked herself in her office until she finished it. It was, she said, “a Mt. Everest among cliffhangers.” I was feeling pretty good until she sandbagged me at the end: “Of course, I always did like Chinese food.”

In other words, I’d given her a few hours of guilty pleasure but I wasn’t a serious writer providing solid sustenance. I was guilty as charged, of course, but consoled by a $250,000 paperback sale and a movie deal. A few years later I saw another review in which that same writer confessed that, after much soul-searching, she had decided that it was all right to enjoy popular fiction. I was happy for her.

A lot of people have a hard time making the leap from officially-approved “literary” fiction to novels that are fun, and they aren’t all refugees from the Fifties. I received an e-mail recently from a college student in Houston, an English major, asking what thrillers he should read – or whether he should read them at all: “I am racked with guilt if I read any of this stuff. Life is short. I haven’t finished all of Dickens or Shakespeare. Do I have time for detective novels?” I could only advise him that life is a lot longer than he at present understands and there is time for, say, Elmore Leonard and Dennis Lehane, along with Dickens and Shakespeare.

The more I read, the more I saw that Marie, in putting me on the thriller beat, had given me the new mainstream of American popular fiction to splash about in. I want to examine this new mainstream and how it came about. I want to show who the good writers are and why -- and, to a lesser degree, who some bad ones are and why. It seems to me beyond dispute that the level of talent at work today in thrillers and crime fiction is superior to anything that has previously existed in America or Great Britain. I say this having recently reread a number of acclaimed crime novels that I first read several decades ago. Alas, the books we loved in our youth, like the sweet young things we dallied with, have not always aged well. Our memories play tricks on us and often we have been misled by movies that vastly improved the original material. Nostalgia is the sweetest of drugs but it will cloud our minds, distort our memories, and lead us into error if we let it.

We must ask why thrillers have become increasingly popular. Of course, stories of danger and suspense have always had visceral appeal. Lee Child, author of the Jack Reacher series, once summed this up nicely:

“In human evolution we developed language, we developed storytelling, and that must have been for a serious purpose. I think right from the cave man days, we had stories that involved danger and peril, and eventually safety and resolution. To me that is the story. And that’s what we’re still telling today, 100,000 years later. That’s what a page-turner is.”

But there are contemporary reasons for the triumph of the thriller as well. One is the transformation of the book business. Once hailed as a “gentleman’s profession,” publishing today is more like a barroom brawl as corporate takeovers have intensified bottom-line pressures on editors. And the bottom line is that thrillers sell, which means there is a continuing scramble to find the writers who can produce books that translate into corporate profits. There are other social and cultural factors of course. Decades of war, recession, and political and corporate corruption have made Americans more cynical – or realistic – and thus more open to novels that examine the dark sides of our society. And yet most thrillers manage some sort of a happy ending. They have it both ways, reminding us how ugly and dangerous our society can be and yet offering hope in the end. Thrillers provide the illusion of order and justice in a world that often seems to have none.

Of course, we read for fun too. We love the excitement of suspense. We want to know whodunit. Indeed, these days, we love suspense more than sex, at least in books. In the 50s and 60s, sex was a huge element in popular fiction, from I, the Jury to Peyton Place to Portnoy’s Complaint and countless others. Today we’re up to our ears in sex. Who wants to read about it? The books I’m discussing contain relatively little sex and dirty talk, nothing like what we endure on HBO. In the modern thriller, suspense has replaced sex as the engine that drives popular fiction.

As thrillers have become more popular, and their potential rewards greater, more of the most talented young writers, those who a generation ago would have been drawn to anguished novels about their unhappy childhoods, are instead trying to become the next Grisham or Grafton. The level of their work has risen until the best of today’s thrillers are the white-hot center of American fiction. We hear talk about this or that “golden age” of yesteryear. Forget it. Right here, right now, is the golden age of thrillers, some of which transcend genre. The Silence of the Lambs and Mystic River are excellent examples. Both novels – and the Oscar-winning movies made from them – are vastly more sophisticated and powerful than their counterparts from earlier eras.

This book is not about me – often a vital point for a writer to grasp – but it is indisputably by me, so I think it reasonable to say a little about my background, preferences, and prejudices. The central fact is that, as reader and reviewer, I fall into three related categories – bookworm, middlebrow, and writer.

The turning point in my life came when I was four and spent a year living with my maternal grandparents. My grandmother was a fussy little woman who decided it was high time I learned to read. I remember sitting on the floor as she stood at a blackboard and taught me my ABCs. Soon I was reading the Sunday comics and then books. I still have the copy of Huckleberry Finn she gave me the Christmas I was six. I was never much of a student – I was bored in the early grades and rebellious in high school – but I read a lot and could always write an essay or book report; in a pinch I would make up the book. Most of what I learned in my early years resulted from taking the bus to the Fort Worth Public Library each Saturday morning, checking out the maximum of five books, reading them, then going back the next Saturday for five more. The Hardy Boys were my first crime series, if you don’t count the Dick Tracy comic strip.

My mother kept bestsellers around the house. The first grown-up novel I remember reading, at twelve or so, was The Robe, which featured one hell of an exciting swordfight. I loved George Orwell’s Animal Farm without having a clue about its political message. I devoured the short stories of Mark Twain, who did a great deal to corrupt my young mind. When I was a teenager, you could feel awfully isolated in Texas if you weren’t part of its dominant culture, which was based on football, oil, Cadillacs, and country clubs. You were always listening for faint signals from afar, evidence that others out there shared your discontent. By high school I was deep into Somerset Maugham, whose views were decidedly un-Texan, and Sinclair Lewis, who encouraged me to scorn the George Babbitts and Elmer Gantrys I saw around me.

I spent two years at North Texas State, in nearby Denton, where my fellow students included Pat Boone, who joined my fraternity before he dashed off to stardom, and Bill Moyers, who a decade later I would meet again in the White House. Larry McMurtry arrived on campus just after I left; we both took a writing course from Dr. James Brown. Life was good at North Texas – except that, like many an impressionable lad of that era, I had come under the spell of F. Scott Fitzgerald. I dreamed of Princeton’s ivory towers. Alas, I lacked the money – not to mention the grades – to enter that distant paradise. But I had a friend at the University of the South, in Sewanee, Tennessee, and I managed to scrape together the wherewithal to enroll there.

Until then I had read at random. At Sewanee, people were actually teaching me. I took a good course on Shakespeare and a great one on the Renaissance poets, taught by an incomparable Alabaman, Dr. Charles Trawick Harrison. It was the most important course in my college career. Once you begin to appreciate the majesty of Andrew Marvell’s “But at my back I always hear / Time’s winged chariot hurrying near” and the music of Robert Herrick’s “Gather ye rosebuds while ye may/ Old time is still a-flying,” you start to grasp the potential of our language. I also took a course in the Romantic Poets that bored me and one in Literary Criticism that baffled me. I was starting to realize that there were highbrows in the world and there were middlebrows and I was among the latter. I sat in Lit Crit with young men who would go on to be distinguished professors at leading universities – John Fleming at Princeton, John Evans at Washington and Lee, Bernie Dunlap at the University of South Carolina, Henry Arnold at Sewanee – and it was clear that they had intellectual concerns that I didn’t share.

In my contemporary lit class, I delighted in Hemingway and Fitzgerald but never ventured far into Faulkner or finished Moby-Dick or War and Peace. Today, I would say that my favorite novels are The Great Gatsby, Huckleberry Finn, and Lonesome Dove, and I’ve taken pleasure from many other writers, including Graham Greene, Philip Roth, John Updike, John O’Hara, Flannery O’Connor, Ann Beattie, and J.D. Salinger, as well as many of those I’ll discuss in these pages.

Upon graduation, when my more scholarly classmates went off to graduate school, I got myself hired as a $65-a-week reporter for the Nashville Tennessean. It was there that I did my first professional book reviewing -- I guess you’d call it professional; they didn’t pay you but you got to keep the book. Later I made my way to Washington to work in the Kennedy Administration and then to pursue a writing career. During the late 1960s, about the time that my first book came out, I enjoyed a brief run as a young hot-shot. For a time I was busily writing for The New York Times Magazine and reviewing for both the Washington Post and the New York Times Book Review; in 1969 the latter ran my piece on Theodore White’s The Making of the President: 1968 on its front page. Alas, my status as hot-shot faded when I decided to focus my energies not on journalism but the more daunting business of writing novels.

All of which brings me to my third category: writer. I’ve published nine novels, at least two of which weren’t bad (Lords of the Earth and The President’s Mistress, if you must know) and several books of nonfiction. I review novels as one who has written them. I know all the problems and most of the tricks and I usually know when the writer is at the top of his game and when he’s faking or just doesn’t have the moves.

I have vast sympathy for writers. It’s not so hard to write a publishable novel, given certain basic skills, but it’s damned near impossible to write a really good novel, and I respect those who do. Writing is a tough, lonely business. You see illiterate hacks getting rich while you can’t pay your rent. No matter how good you are, there are people who are better, legions of them. When you’re young, and your book is published, you race out each Sunday morning and seize the New York Times Book Review, searching for the acclaim that will bring you fame and fortune, and it takes many months to grasp that the bastards aren’t going to review you.

The Times once published a brief, harsh review of a first novel. A few Sundays later they published the author’s one-sentence letter to the editor: “You have broken my heart.” Writing can indeed be heart-breaking, but sometimes, if you have talent, perseverance, and luck, you can survive, even prosper. As McMurtry notes somewhere, after a lifetime of toil, you might advance from “promising” to “minor.”

It annoys me to see fine writers dismissed as genre writers – crime novelists, spy novelists and the like – by those who salivate over the latest incomprehensible postmodern gimmickry. A book is a book is a book. Labels are necessary to organize bookstores but serious readers should pay them no mind. In what follows, I will follow one paramount rule: to judge writers not by their reputations but by the words they put on paper. Reputations are what other people think; this book is what I think.

I don’t expect everyone to agree with my views. We all have different tastes, often amazingly so. Not long ago I mentioned my admiration for George Pelecanos and Michael Connelly to a crime writer I respect. He replied that “for reasons I can’t fully comprehend I can’t force myself through Pelecanos” and that he finds police procedurals “to be tediously dull – so there goes Connelly.” I thought this quite perverse – but probably no moreso than readers will find some of my opinions.

I should issue two warnings. First, there are scores of fine writers at work today and I can’t include them all. I wish I could. Second, in discussing books, I will from time to time reveal their endings. So if you don’t want to know who killed Roger Ackroyd, or who plotted the Kennedy assassination in The Tears of Autumn, or what surprise brought joy to Harry Bosch’s tormented life, proceed with care, because in these pages the truth will sometimes out.

While I was writing this book, more than a hundred writers formed the International Thriller Writers Inc. The new organization reflected a belief that thrillers and mysteries are distinct categories and also that the venerable Mystery Writers of America, which presents the annual Edgar (for Edgar Allan Poe) Awards, favored mysteries over thrillers. The group’s web site, thrillerwriters.org, contains a list of all-time top thrillers. Their definition of a thriller, like my own, is inclusive, and reaches back to such classics as Wilkie Collins’s The Woman in White, Robert Louis Stevenson’s The Strange Case of Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde, Oscar Wilde’s The Picture of Dorian Gray, and Bram Stoker’s Dracula, before advancing to Graham Greene’s The Third Man, Patricia Highsmith’s Strangers on a Train, Richard Condon’s The Manchurian Candidate, Thomas Harris’s Red Dragon, and John Grisham’s The Firm, among many others. Neither Hammett nor Chandler is listed, because they are viewed as having written private-eye or detective novels, not thrillers. (To further complicate matters, most of today’s private-eye novels are considered thrillers, simply because of their level of violence.)

Lists are fun, but all contemporary judgments are suspect. The only real test of literature is what one of my professors called “universal acceptance.” That doesn’t mean that Tom Clancy is a great writer because he’s sold millions of books. It means that Mark Twain and Charles Dickens are great writers because educated opinion has for more than a century continued to regard them as great writers – and because we common folk have continued to read them. The future will have the last word. But that doesn’t mean that we shouldn’t duke it out in our own time.

Jonathan Yardley, the Post’s Pulitzer Prize-winning book critic, once wrote that Edmund Wilson “saw it as his mission to introduce worthy writers to intelligent lay readers.” Clearly, I’m not Wilson and the authors I’m championing are not the celebrated modernists he admired, but I like to think I share that admirable goal – to introduce worthy writers to intelligent readers. There are a lot of both out there and I hope this book helps bring them together.

2. Crime Past: Poe, Doyle, Christie

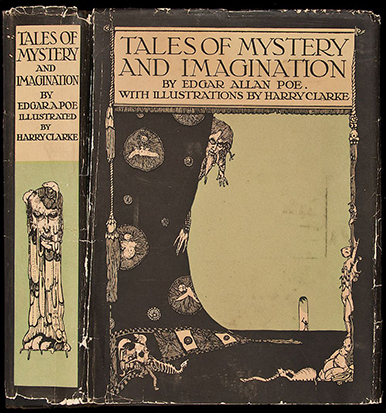

A case can be made that the first great thrillers were classics like Oedipus Rex (king/investigator finds killer: himself) and Hamlet (prince/investigator dithers), but it is generally agreed that the detective story was invented by Edgar Allan Poe in his story “The Murders in the Rue Morgue,” published in April 1841 in Graham’s Magazine in Philadelphia. In concocting that story, Poe moved beyond another, related genre he had already perfected: the tale of horror. I remember at age twelve or so discovering Poe’s horror stories – “The Pit and the Pendulum,” “The Cask of Amontillado,” “The Tell-Tale Heart” -- and being dumbfounded. Nothing in the Black Beauty or Lassie Come Home had prepared me for Poe’s dark vision. He was a troubled man with a wildly inventive mind who was far ahead of his time.

“The Murders in the Rue Morgue” is plenty horrific but, unlike Poe’s horror stories, it held out the possibility that human reason -- in the person of a private detective, a man of superior intellect -- could triumph over madness. It is also an extremely odd story. In the edition I have, it’s forty-five pages long and the first four and a half pages – a tenth of the story – are devoted to tedious remarks on “the analytical power.” A modern editor would have cut this digression, in part because Poe’s detective makes the same points again in the body of the story.

Finally the real story starts: “Residing in Paris during the spring and part of the summer of 18--, I there became acquainted with a Monsieur C. Auguste Dupin. This young gentleman was of an excellent – indeed of an illustrious family, but, by a variety of untoward events, had been reduced to such poverty that the energy of his character succumbed beneath it, and he ceased to bestir himself in the world, or to care for the retrieval of his fortunes.”

The unhappy Dupin and the unnamed narrator share a love of books and decide to share a house. The narrator soon concludes that Dupin is the most fascinating fellow he’s ever met. He is particularly taken by Dupin’s “peculiar analytic ability” and gives us a dramatic example. The two of them are out walking and have been silent for fifteen minutes. Abruptly, Dupin refers to an actor they both know. The narrator had indeed been thinking about that very actor, and says, “Dupin, this is beyond my comprehension. I do not hesitate to say that I am amazed and can scarcely credit my senses. How is it possible you should know I was thinking of --?” Dupin explains that fifteen minutes earlier a man carrying a basket of apples had nearly knocked the narrator down, and goes on to explain the train of thought that led him from the apples to the actor.

This demonstration of Dupin’s mental powers is followed by their reading in the newspaper about the murder of a mother and daughter at their home in the aptly-named Rue Morgue. The murders were unspeakably violent and clearly committed by someone of great strength. Neighbors heard the women screaming. Before they were able to force their way into the women’s fourth-floor apartment they heard a shrill voice that spoke in a language no one recognized. The doors and windows to the apartment were locked from the inside. There seems to be no way anyone could have entered or left the apartment.

Dupin knows the Prefect of Police and receives permission for himself and the narrator to examine the crime scene. He studies it and the victims’ bodies and soon deduces the identity of the killer, which he explains as the narrator listens “in mute astonishment.” When examining the windows that appeared impossible to open, Dupin found concealed springs that make them open easily. Having discovered how the killer could have come and gone, he next noticed a lightning rod that he could have used to climb up to the windows. He further discovers a “little tuft” of hair that he has “disentangled” from the “rigidly clutched fingers” of one of the victims – and that the police had missed. He notes that the bruises on the throat of one victim were too small to have been made by a human hand. He has also found a piece of ribbon the police missed, the sort that sailors use to tie up their hair.

Putting all this together, and noting that the killer seems stronger, more agile, and more brutal than a human, Dupin concludes that the killer was a “large fulvous orangutan of the East Indian Islands.”

He puts an advertisement in Le Monde in which he claims to have found a lost orangutan and invites its owner to come claim the creature. Before the sailor arrives, Dupin and the narrator arm themselves lest he proves violent. As it turns out, the sailor admits that his orangutan escaped from him and carried out the killings. He agrees to tell the police what happened. The Prefect of Police, rather than thank Dupin, says he should mind his own business, but Dupin tells the narrator, “I am satisfied to have defeated him in his own castle.”

Thus ends the world’s first detective story. It works because Poe, like Conan Doyle after him, played upon our willingness to identify with the brilliant detective and to scorn the clueless cops. The solution of the mystery -- death by killer ape -- is colorful, but not really satisfactory by today’s standards. In real life one could go decades, perhaps centuries, without seeing two women murdered by an escaped orangutan armed with a razor. Poe’s genius was in inventing the genre, not in creating a murderous monkey. In one burst of inspiration, he had given us the private detective who scorns the inept police, the locked-room mystery, and the detective’s sidekick/narrator who would be the model for countless other second-bananas of criminal detection, most notably Dr. Watson.

Nothing is more striking about the story than our awareness of how much Doyle would soon borrow from it. The eccentric, moody Holmes has much in common with Dupin. The narrator of the Dupin stories, like Dr. Watson, not only moves in with his hero but tells us endlessly how brilliant he is. Dupin’s seeming ability to read the narrator’s mind is reflected in the many times that Holmes dazzles Watson by announcing that some passerby is a left-handed Lithuanian who loves polkas and hates his mother. Dupin’s putting an ad in the newspaper to summon the criminal, and the two men arming themselves, are devices often seen in the Holmes stories.

Poe wrote two more Dupin stories, “The Mystery of Marie Roget” and “The Purloined Letter.” The former is sixty-seven pages long and all but unreadable. Poe tells the story of Marie Roget’s death – her body is found in the Seine – by having Dupin and the narrator read newspaper accounts of the crime and discuss what they prove or don’t prove. Once again, many of the clues are absurdly simple – a cloth is tied around the victim’s body with a “sailor’s knot,” which leads Dupin to suspect a young naval officer. The point of the story is that Dupin solves the crime without even visiting its scene. It is enough for him to apply his intellect to the facts. Other armchair detectives would follow, starting with Sherlock Holmes’s smarter brother Mycroft.

The other story, “The Purloined Letter,” concerns a missing letter which could somehow inspire a royal scandal. The police search the apartment of the suspected thief, a government Minister, without success; only Dupin, by putting himself inside the mind of the villain, realizes he would not conceal the letter but would leave it out in the open – hide it in plain sight.

Writers have offered complex interpretations of the Dupin stories. David Lehman, in his book The Perfect Murder, suggests that Poe’s invention of the detective story is connected to the death of Romanticism “with its worship of the noble savage.” Surely it is no accident, he says, that in the world’s first detective story, “the culprit turns out to be a ghoulishly transmogrified version of the noble savage.” He says that the orangutan’s dark deeds were those of “the id on a monstrous rampage, primitive energy uncontrolled, Romanticism gone haywire.”

Perhaps so, but for our purposes, let’s just call a spade a spade and an orangutan a bloody ape, and keep in mind that poor, doomed Eddie Poe paved the way for Sherlock Holmes.

Two Classics

Wilkie Collins (1824-1889) was a close friend of Charles Dickens and, like Dickens, he wrote big, complex novels packed with characters and events, notably The Woman in White (1860) and The Moonstone (1868). Collins was the first writer to see that mystery novels could be as rich and ambitious as those of his friend Dickens. The Woman in White is a strange, mysterious tale of love, deceit, mistaken identity, a forced marriage, a loyal sister, and retribution – there had been nothing like it before. The Moonstone, even more exotic, concerns a priceless diamond, stolen from India and brought to England with a curse on it that leaves death and destruction in its wake. T.S. Eliot called it the first and best of English detective novels. In it, departing from Poe’s incompetent cops, Collins introduced the admirable Sgt. Cuff of Scotland Yard. Collins was overshadowed by Dickens as a novelist and by Doyle as a crime writer, but these two novels hold up admirably today, certainly better than Doyle’s. His tale of the cursed Indian moonstone is echoed in Doyle stories like “The Sign of the Four” and the Gothic scope of his novels influenced 20th-century writers like Lawrence Sanders and Thomas Harris. The Moonstone and The Woman in White are the first great crime thrillers, essential reading for anyone with a serious interest in the literature of suspense.

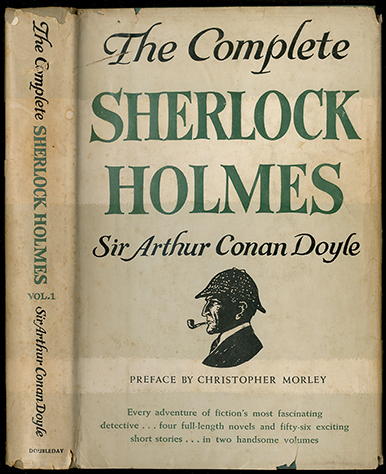

Elementary, My Dear Watson

There are people who study the Holmes stories with Talmudic zeal. King Lear and his Fool have never been examined with more intensity than have Holmes and Watson by these Sherlockians, as they call themselves. The more extreme Sherlockians reject Conan Doyle and treat Holmes as a historical figure whose adventures were written by his friend Dr. Watson. Doyle is dismissed as Watson’s literary agent.

I am no Sherlockian but in rereading some of the stories I enjoyed them. How could anyone who admires vivid, imaginative, fast-moving, suspenseful prose not? Yet I think the greatness of the stories is widely misunderstood. Holmes is famous as the ultimate genius of crime-fighting, a mental superman whose brooding mind saw answers that were invisible to ordinary mortals. He endlessly lectured Watson – and us – on the powers of deduction and generations of readers have bowed to his superior intellect.

All this is twaddle. Doyle’s genius was his ability to play games with us. Time after time, Holmes’s supposedly dazzling solutions turn out to be simple, even silly. The writer holds all the cards in this game. He has crafted his puzzle in advance and tosses out various clues, some relevant but most there to tantalize the reader. We don’t reread the Holmes stories because of the puzzles but despite them, because we love the exciting, warm, comforting, now-vanished world that Doyle summons up. With this in mind, let’s look more closely at the Holmes stories.

We start with the young Conan Doyle, who in the spring of 1886 was practicing medicine at Southsea but burned with a passion to write. He had been deeply impressed as a medical student by a professor who stressed the use of close examination and relentless logic in diagnosing patients. Doyle had read Poe and Collins, and he had the idea for a detective, not unlike Dupin but English, who would solve crimes by his powers of observation and analysis.

Doyle’s first published story, “A Study in Scarlet,” is an odd, awkward tale. It opens with Watson’s first-person account of meeting Holmes. We learn that Watson has been an army doctor in “the second Afghan war.” He was wounded there and sent to London to recover. The first thing Holmes says to him is “You have been in Afghanistan, I presume.” “How on earth did you know that?” Watson replies -- “in astonishment” -- but Holmes only chuckles. The two men agree to share lodgings at 221B Baker Street. Holmes tells Watson more about “the science of deduction” and confesses “I have a trade of my own. I suppose I am the only one in the world. I’m a consulting detective.” Holmes explains how he knew Watson had been in Afghanistan: “The train of reasoning ran, ‘Here is a gentleman of the medical type, but with the air of a military man. Clearly an army doctor, then.’” There is more of this, then Watson says agreeably, “You remind me of Edgar Allan Poe’s Dupin.” Holmes rejects the compliment, saying that he found Dupin “a very inferior fellow.”

The loyal, plodding Watson is never as colorful or interesting as Holmes, but he is absolutely central to the stories’ success. We see Holmes through his eyes, with his mixture of affection and awe. Watson never tires of telling us that Holmes is the most fascinating man on earth and most readers come to accept his judgment even when the evidence does not support it.

Scotland Yard asks Holmes’ help. An American has been found dead in a deserted house. The clues include a woman’s ring, the word “Rache” written on the wall in blood, and footprints and tire tracks that Holmes understands but the police do not. When one of the policemen announces that obviously a woman named Rachel is the key to the mystery, Holmes informs him that “Rache” is German for “revenge.” Holmes calls upon “six dirty little scoundrels” – the Baker Street Irregulars -- to assist his investigation, showing that Doyle appreciates the utility of children in fiction. After a second American is killed, Holmes calls for a cab and, when the driver arrives, snaps handcuffs on him and announces that he is the killer. This man, Jefferson Hope, confesses.

We have been reading for 35 pages, we have the killer, and we have no idea who Jefferson Hope is or why he killed the two Americans. Doyle then launches “Part 2” of the story. Watson’s narrative stops and we begin a third-person account that is set in “an arid and repulsive desert” in “the central portion of the great North American Continent.” It is some years earlier, 1847, and a man and a little girl, the only survivors of a wagon train, are rescued by a group of Mormons headed for their Promised Land in Utah. The Mormons demand that the man join their religion along with the child, whom he has adopted. He does, although he never adopts their polygamy.

Some years later the brutish Mormons demand that he give up his adopted daughter to a man who already has seven wives, but the father refuses. He is killed and the young woman is forced into marriage and dies. She is survived by the man she truly loved, Jefferson Hope, who vows revenge and obtains it years later when he follows the Mormon who stole his love and another man to London. This flashback to America takes 25 pages. Then Watson resumes his narrative and Hope confirms that he had become a cab driver in London and thereby tracked down and killed his victims. The problem of what to do with Hope, whose murders seem justified, is solved when he dies of a heart condition.

For all Holmes’s deductive skill, the turning point in the case came when he sent a telegram to Cleveland, where the first victim had been living, and inquired about the man’s marital status. The Ohio police sent back word that the man “had already applied for the protection of the law against an old rival in love, named Jefferson Hope, and that this same Hope was at present in Europe.” It was a simple matter for Holmes, aided by his “Arab detective corps,” to find the cab driver named Hope, who had helpfully continued to use his real name. Scotland Yard could as easily have asked the right question of the Cleveland police. The story ends with Watson vowing to tell the world of Holmes’s amazing powers.

In fact, Holmes’s amazing powers consisted of sending a telegram. Realizing that his crime story was thin, Doyle then took us halfway around the world to portray a lurid tale of rape and murder among the Mormons. Doyle surely hoped that such scandalous events would strengthen his chances of selling his story.

As it turned out, he had a hard time selling it. It was an awkward length, long for a story and short for a novel. Two publishers turned down “A Study in Scarlet” before Ward Lock & Co. offered to include it in Beeton’s Christmas Annual for 1887. Then Doyle got lucky. An editor of Lippincott’s Magazine liked the story and asked Doyle for a follow-up. Consider Doyle’s plight at this point. It has taken him more than a year to get his first story published. Now he is given one more chance to get Holmes before the public. So what does he do? He does what any writer worth his salt would do: he writes his ass off.

Holmes second adventure, “The Sign of the Four,” probably contains more thrills per page than any story ever written. In its opening sentence, Holmes is injecting himself with cocaine (the famous seven-percent solution), much to Watson’s displeasure. Soon a young woman arrives, a damsel in distress. Her soldier father, she explains, has vanished some years earlier, but she has been sent “a very large and lustrous pearl” every year since, and now she has been summoned to a mysterious meeting by an “unknown friend.” Holmes agrees to accompany her. Watson, for his part, is already falling in love with Miss Mary Morstan. She produces a letter of her father’s that refers to “The Sign of the Four.” That night, after a wild ride in a closed carriage, they are admitted to an isolated house “by a Hindu servant, clad in a yellow turban” and meet the master of the house, a bizarre little man named Thaddeus Sholto. He says that Mary will be given a vast fortune in jewels that her father brought back from India. However, Sholto’s brother has the treasure chest, and when they reach his house the brother is dead, in an inaccessible locked room, apparently killed by a poisoned thorn. Holmes finds evidence of a “wooden-legged man” and footprints suggesting that the killer was only half the size of an adult man. “Holmes,” Watson gasps, “a child has done this horrid thing.” The treasure chest is missing.

Holmes employs a dog named Toby to help him track the killers (dogs, like children, are mainstays of adventure stories), then unleashes the Baker Street Irregulars to find the killer’s boat, which leads to a wild chase down the Thames (“Our boilers were strained to their utmost.”) Holmes captures the peg-legged killer and his tiny, dark-skinned associate (“that little hell-hound Tonga,” he of the poisoned darts) and we learn the story of how some Englishmen stole a fortune in jewels during the Indian Mutiny. The “Four” of the title were convicts who thought the treasure theirs. Holmes solves the locked-door murder – that little hell-hound Tonga, like the orangutan in “The Murders in the Rue Morgue,” could scramble to places most mortals cannot. The jewels are lost at the bottom of the Thames, but Watson marries Mary, the true treasure. Whether she is his first or second wife is a subject of continuing debate among Sherlockians.

In short, Doyle’s first two stories are less exercises in deduction than exotic action adventures, with innocent virgins dragged to harems in Utah and pint-size savages wielding blowguns on the streets of London. Holmes, hitching rides on the backs of carriages, racing down the Thames in a speedboat, and sending his scruffy little “Arabs” into the street, has less in common with C. Auguste Dupin than with Indiana Jones. Yet the stories are gloriously readable. In 1890 “The Sign of the Four” was published in Lippincott’s American and English editions and came out in book form. Doyle was sufficiently encouraged to close his medical practice and launch a series of stories in the Strand Magazine that made him famous. There is a saying among writers that you must trust your material. As his success grew, Doyle came to have more faith in Holmes and Watson and to feel less need for polygamy and blowguns.

Doyle’s next story, “A Scandal in Bohemia,” is simple compared to the first two. Holmes and Watson are visited by a huge masked man who proves to be the King of Bohemia. He explains that he is about to marry but fears that a former lover will use a photograph to embarrass him. This is, he declares, “a matter of such weight that it may have an influence on European history.” It happens that the woman in question, Irene Adler, is the woman in the world Holmes most admires, but that is not central to the events that follow. The king, whose agents have already broken into Adler’s house and searched without success for the photo, persuades Holmes to try to find it.

Holmes arranges for his confederates to fake a fight outside Adler’s home during which an old clergyman is seemingly injured. She takes the poor fellow inside to recover. Watson, outside, shouts “Fire!” The woman hurries to the photograph’s hiding place (“a recess behind a sliding panel”) before she realizes there is no fire. The clergyman is Holmes in disguise so now he knows where the photograph is hidden. Here is Holmes’ superior intellect at work: “When a woman thinks that her house in on fire, her instinct is to at once rush to the thing which she values most.” This is genius? The story, a jazzed-up variation on Poe’s “Purloined Letter,” is child’s play as to criminal detection but pulls the reader in with fancy talk about changing the history of Europe and dark hints of the scandalous ways that fine ladies and Bohemian kings conduct their romances.

Next, in “The Red-Headed League,” Holmes solves the mystery when a pawnbroker tells him that his assistant has a “white splash of acid upon his forehead,” Holmes springs into action, for he knows that the man with the acid scar is one of the most dangerous criminals in London. (“He’s a remarkable man, is young John Clay. His grandfather was a Royal Duke, and he himself has been to Eton and Oxford.”). Holmes thus foils a bank robbery and seizes the blue-blooded criminal. (“’I beg that you will not touch me with your filthy hands,’ remarked our prisoner, as the handcuffs clattered upon his wrists. ‘You may not be aware that I have royal blood in my veins.’”)

Must I continue? In story after story, the solution is childlike in its simplicity. Even run-of-the-mill crime writers today devise more ingenious plots than Doyle. And yet Doyle’s stories have survived for a reason. He was a writer. His stories capture us not with their “scientific deduction,” but with their zest, their portrait of London, and the chemistry between his two great characters. They are an excuse for us to enter a world that is ordered and dignified, a world where rationality triumphs over evil, a world still innocent of the horrors that began in 1914. The Holmes stories made it clear for the first time that mysteries could attract a vast audience. The excitement that surrounded the Holmes collections, particularly when Doyle brought Holmes back after his apparent death, wasn’t equaled in England until the Harry Potter books a hundred years later. Indeed, the secret of the Holmes stories is that they are magnificent boys’ adventures that continue to work after the boys grow up. If, indeed, we ever grow up.

Others share this view. Christopher Morley, in his introduction to the complete Sherlock Holmes, wrote: “Even in the less successful stories we remain untroubled by any naiveté of plot; it is the character of the immortal pair that we relish.” Somerset Maugham wrote in his essay “The Decline and Fall of the Detective Story”: “For an anthology of short stories that I was preparing several years ago, I re-read the collected stories of Conan Doyle. I was surprised to find how poor they were. The introduction is effective, the scene well set, but the anecdote is thin and you finish the tale with a sense of dissatisfaction. Great cry and little wool.” Yet Maugham goes on to say, “No detective stories have had the popularity of Conan Doyle’s, and because of the invention of Sherlock Holmes I think it may be admitted that none has so well deserved it.” The Holmes stories remind us that the stories we love best are character-driven. With that in mind, let us turn to Doyle’s most successful imitator, Agatha Christie.

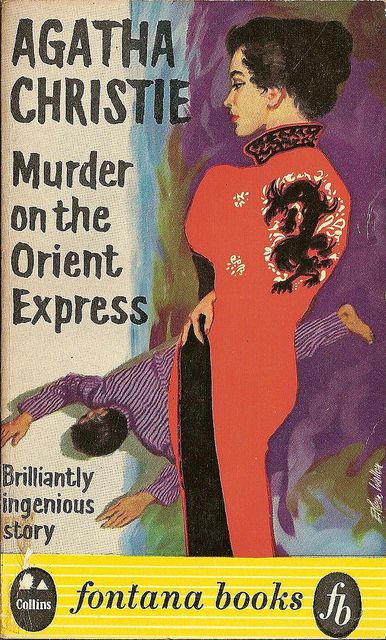

There Is Nothing Like a Dame

My first encounter with Dame Agatha Christie (1890-1976) was a happy one. I must have been in my early teens when I saw Rene Claire’s movie of Christie’s And Then There Were None. I remember the moody black and white photography and the devilish plot in which ten strangers are summoned to a deserted island where someone starts to kill them. Finally, the last survivors, two young lovers, confront one another, each believing the other is the killer. But, of course, Christie still has tricks up her sleeve.

I read a few of Christie’s novels in my youth but I was essentially innocent of her work when I sat down one autumn day in Paris to read Peril At End House, a 1931 Hercule Poirot mystery that I’d picked at random at Shakespeare & Company. The novel opens with Poirot and his friend Captain Arthur Hastings vacationing on the Cornish coast. They are obviously modeled on Holmes and Watson – the brilliant, world-famous detective and his stolid biographer/friend. Although Hastings later married, he and Poirot once shared lodgings, like Holmes and Watson, and they bicker like an old married couple.

The first thing Poirot says to Hastings is “Your remark is not original.” Hastings recalls a mystery “solved by Poirot with his usual unerring acumen.” Poirot says he wishes Hastings had been with him during that case. “As a result of long habit,” Hastings reflects, “I distrust his compliments.” Sure enough, Poirot adds, “One needs a certain amount of light relief.” Poirot claims to be retired from the detective business and Hastings urges him to reconsider. No, Poirot says, “They say of me, ‘That is Hercule Poirot! – the great – the unique! There was never anyone like him, there never will be!’ Eh bien – I am satisfied. I ask no more. I am modest.” Poirot is “almost purring with self-satisfaction.” Later, when Hastings insists that Poirot’s career is not finished: “Poirot patted my knee. ‘There speaks the good friend – the faithful dog. And you have reason, too. The grey cells, they still function…’”

By then I was in shock. Christie had transformed Holmes and Watson from the sublime to the ridiculous. She had made them comic characters – the fussy, absurd little Belgian with his “egg-shaped head” and his dense, oft-ridiculed sidekick. Holmes and Watson were classics of male bonding, up there with Mark Twain’s Huck and Jim and Larry McMurtry’s Gus McCrae and W.F. Call. Poirot and Hastings are closer to Abbott and Costello. And there is a cruel undercurrent to the exchanges. Comic relief! My faithful dog! Holmes was a gentleman who treated the loyal Watson with respect. Poirot needs a punch in the nose.

I tried to imagine what Christie was up to, for she was a clever woman, whose books have been outsold only by Shakespeare and the Bible. I can only surmise that, setting out to imitate the Holmes stories, decided to alter the formula. If Holmes had any fault as a character it was that he was both rather grim and a bit of a smarty-pants. That did not impede his success but it could perhaps be improved upon. So Christie made her master detective not only a foreigner (not French but close to it) but a rather absurd one. We could laugh at Poirot and still reluctantly admire his alleged genius. He provided comedy and intellectual fireworks in the same package. It is true, too, that Christie began writing in the immediate aftermath of the First World War, with its unspeakable loss of life, and she may have felt that people needed to laugh.

Peril at End House is a comedy of manners, built around mysterious events and the murder of one minor character. Poirot and Hastings meet Nick Buckley, an attractive young woman who owns End House. She is a modern woman who drinks Martinis and has a “hint of recklessness” about her, and it appears that someone is trying to kill her. The plot expands to include a young pilot who is attempting to fly around the world (heady stuff in those days), the death of the richest man in England, a secret engagement, a poisoned box of candy, a drug fiend, a forged will, and finally a séance at which Poirot exposes the killer – who turns out to be the lovely Nick herself! It’s harmless fun, but I never got over the shock of meeting the comedy team of Poirot and Hastings.

Wanting to be fair to Dame Agatha, I sought out one of her most admired novels, The Murder of Roger Ackroyd, which was published in 1926 and inspired Edmund Wilson’s famous 1945 New Yorker essay, “Who Cares Who Killed Roger Ackroyd?” in which the great critic declared that detective fiction was a minor vice, somewhere between crossword puzzles and smoking, but confessed his weakness for the Holmes stories. The Murder of Roger Ackroyd is a far better novel than Peril at End House – take off Christie’s name and you wouldn’t think the same person could have written them both. Captain Hastings does not appear. Poirot has settled in an English village where he is a neighbor of Dr. Sheppard, who narrates the novel and who at the outset thinks Poirot a hairdresser.

The opening chapters, in which we meet the people of the village, are a model of deft exposition. The writing is both amusing – particularly the sketch of Dr. Sheppard’s nosy sister – and perceptive about the place and its inhabitants. Abruptly, the village’s leading citizen, Roger Ackroyd, dies in his home under mysterious circumstances. Poirot solves the murder, which involves the use of a Dictaphone (high technology for that day) to imitate the voice of the dead man, the faking of footprints, and the use of a stranger to make a crucial phone call. In the end, Poirot shows that the killer is none other than Dr. Sheppard, our helpful narrator. Poirot permits the duplicitous doctor to kill himself rather than face justice – this, like Jefferson Hope’s heart attack in “A Study in Scarlet,” removes the need for a messy trial. The ending of the novel aroused a noisy debate. Many readers felt that Dame Agatha had broken the rules by letting the narrator be the killer. Imagine, a mystery novelist deceiving her readers! But the lady was well aware that there are no rules in writing except what works. The writer, if she is good enough, makes the rules.

Christie wrote for some fifty years and produced more than sixty novels, as well as short stories, plays, and an autobiography. There were thirty-three Poirot novels alone. Some of her most-admired novels, in addition to Roger Ackroyd, are The ABC Murders, And Then There Were None, and Death on the Nile, and the Miss Marple series has devoted fans. On the basis of the two novels discussed above, we must call her output uneven, but that is inevitable. (Her rivals Shakespeare and the Bible are also uneven). Dame Agatha had a genius for ingenious plots and her success inspired other writers, many of them women. Some of them wrote mysteries that were more sophisticated but none was more popular.

Patrick Anderson. The Triumph of the Thriller: How Cops, Crooks, and Cannibals Captured Popular Fiction. Random House, 2007.